The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World (23 page)

Read The Marne, 1914: The Opening of World War I and the Battle That Changed the World Online

Authors: Holger H. Herwig

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War I, #Marne, #France, #1st Battle of the, #1914

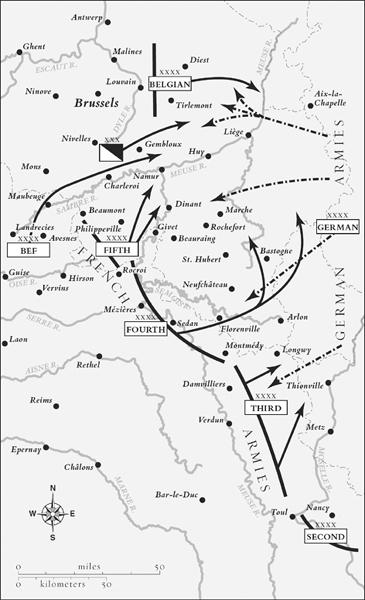

With regard to Fifth Army, Joffre laid out two possible scenarios. If the German right wing marched on both banks of the Meuse in an attempt to pass the corridor between Givet and Brussels, Lanrezac “in complete liaison with the British and Belgian Armies” was to oppose this movement by outflanking the Germans from the north. But if the enemy deployed “only a fraction of his right wing” on the left bank of the Meuse, then Lanrezac was to wheel his forces east to help the drive through the Ardennes planned for Third and Fourth armies. The British and the Belgians would be left to deal with the German units in Belgium. For an army consisting of three corps and seven divisions spread over a front nearly fifty kilometers wide and on the move up to the Sambre, Special Instruction No. 13 was impossible. Lanrezac ignored it and continued his drive north, drums beating, bugles blowing, flags flying, and the men lustily singing the march “Sambre-et-Meuse.”

JOFFRE’S REACTION TO THE GERMAN ADVANCE

Mercifully for Lanrezac, at 5

PM

on 21 August, Joffre, appreciating his commander’s “impatience,” sent out his third order (Instruction particulière No. 15).

12

It canceled the first option previously laid out for Fifth Army. The time had come to mount the offensive that Joffre had planned for years: Ruffey’s Third Army, now divided in two (Third Army and a new Army of Lorraine under Michel-Joseph Maunoury), was to charge toward Arlon in Belgium; Langle de Cary’s Fourth Army was to cross the Semois River and drive on Neufchâteau. From Verdun to Charleroi, the decisive moment for the great French offensive by nine corps of 361,000 men was at hand. At the same time, Special Order No. 15 gave Lanrezac the green light to attack “the northern enemy group,” specifically, Bülow’s Second Army, in concert with whatever British and Belgian forces were on his left. The precise “line of demarcation” between British and French units was left for Field Marshal French and General Lanrezac to decide. Berthelot cheerily informed Lanrezac that since the French were about to drive through the Ardennes on their way into Germany, the more enemy troops committed to Belgium, “the easier it will be for us to break through their center.” It was one of those typical orders from Berthelot that, in the words of historian Hew Strachan, “did not always accord with reality or with realism.”

13

Still, Joffre was downright optimistic. “The moment of decisive action,” he informed War Minister Messimy, “is near.”

14

JOFFRE’S THROWAWAY COMMENT THAT

French and Lanrezac were to decide on the manner of cooperation between their forces was ingenuous, at best. For the first two meetings between the two British and French field commanders had not gone well. The arrogant, combative, and mercurial John French had left Vitry-le-François on Sunday, 16 August, less than impressed with Joffre and his staff.

“Au fond

, they are a low lot,” he informed London, “and one always has to remember the class these French generals mostly come from.”

15

Apparently, the noble squire from Kent had not found a suitable

confrère

in the humble artisan from the Pyrenees. When Sir John incredibly asked GQG to place Sordet’s cavalry corps as well as two French infantry divisions under his command, Joffre was not amused. He brusquely refused.

16

The next day’s meeting between French and Lanrezac at Rethel had been equally disastrous. Lanrezac’s chief of staff, Alexis Hély d’Oissel, met the British contingent with a tart, “At last you’re here; it’s not a moment too soon. If we are beaten we will owe it all to you!”

17

From there, the meeting went downhill. When Lanrezac informed Sir John that the Germans were at the Meuse near Huy, the field marshal in halting French twice inquired what they were doing there and what they were going to do. Lanrezac, who knew no English, allowed his acerbic bile to pour forth.

“Pourqoui sont-ils arrivés?”

he snapped at French.

“Mais pour pêcher dans la rivière!”

*

Henry Wilson, deputy chief of the British General Staff, impeccably translated that for Sir John: “He says they’re going to cross the river, sir.”

18

Tit-for-tat, when Lanrezac asked French for his fresh cavalry division to supplement Sordet’s weary cavalry corps, the field marshal declined. Finally, Sir John stated that the BEF could not be ready for action until 24 August.

19

It would then deploy left of Lanrezac’s Fifth Army on the Sambre. The French must have wondered about the value of British intervention on the Continent.

What to Joffre and Lanrezac could only have seemed haughty behavior on the part of Field Marshal French was, in fact, rooted in British tradition and in “Johnnie” French’s orders. Horatio Herbert Lord Kitchener, Britain’s most famous colonial soldier and in 1914 secretary of state for war, had sent Sir John off to France with the specific instruction “that your command is an entirely independent one, and that you will in no case come in any sense under the orders of any Allied General.”

20

As well, Kitchener—soon nicknamed “the Great Poster” for the famous recruiting poster in which his blazing eyes, martial mustache, and pointing finger loomed over the message your country needs you—had warned the field marshal to exercise “the greatest care … towards a minimum of losses and wastage.” Knowing the French military’s penchant for the all-out offensive

(l’offensive à outrance)

, Kitchener had further admonished his field commander to give “the gravest consideration” to likely French attempts to deploy the BEF offensively “where large bodies of French troops are not engaged, and where your Force may be unduly exposed to attack.” Sir John meant fully to adhere to those instructions.

*

IN THE REAL WAR

, Lanrezac’s weary soldiers moved into position on the afternoon of 20 August. In essence, Fifth Army formed a giant inverted V in the Sambre-Meuse triangle pointing toward the northeast, with German Second Army to the north and Third Army to the east. Franchet d’Espèrey’s I Corps remained on the Meuse, guarding Lanrezac’s right flank, while Gilbert Defforges’s X Corps (with African 37th ID) held the left flank. In the center, Henri Sauret’s III Corps (with African 38th ID) and Eydoux’s XI Corps advanced along the Sambre River between Namur and Charleroi. This vanguard spied the first units of Bülow’s Second Army at 3

PM

on 20 August. Later that night, as previously noted, Joffre ordered Third and Fourth armies to storm the Ardennes, the heart and soul of his grand design, and Lanrezac to attack the enemy on the Sambre around Charleroi. As well, he “requested” Field Marshal French “to co-operate in this action” on the left of French Fifth Army by advancing across the Mons-Condé Canal “in the general direction of Soignies.”

21

Henry Wilson was ecstatic. All the years of planning for British formations to be deployed alongside the French on the Continent were finally coming to fruition. “To-day we start our forward march, and the whole line from here [Le Cateau] to Verdun set out,” he wrote home on 21 August. “It is at once a glorious and an awful thought, and by this day [next] week the greatest action that the world has ever heard of will have been fought.”

22

General Wilson’s burst of enthusiasm was ill founded. The British, Lanrezac furiously informed Joffre, reported that they would not be ready to advance on his left flank for another two days. Around noon on 21 August, Lanrezac demanded precise instructions from Joffre. While he awaited a reply, Lanrezac mulled over his options.

23

Should he cross the Sambre and deny Bülow the heights on the northern side? Or should he entrench his forces on the southern bank and await the arrival of the British on his left flank—as well as the start of the advance into the Ardennes by Third and Fourth armies? In no case was he willing to fight in the Valley of the Sambre, the coal pits and slag heaps of

le borinage

. The “keen intellect” of Saint-Cyr many times had posed similar problems to his students; now he prevaricated and kept his corps commanders in the dark for forty-eight hours.

Joffre let Lanrezac stew. “I leave it entirely to you to judge the opportune moment for you to decide when to commence offensive operations.”

24

But then GQG instructed Fifth Army to advance without the British. Precious time had been squandered. Already on the morning of 20 August, Bülow’s advance guard of cavalry and bicycle units had found two bridges unguarded between Namur and Charleroi. Numerous German cavalry formations in their field-gray uniforms had been mistaken by the local Walloon population as being “English” and showered with food and gifts.

At noon on 21 August, 2d ID of Plettenberg’s Guard Corps had reached the north shore of the Sambre. But Bülow proved to be as cautious as Lanrezac. Neither his cavalry scouts nor his aerial reconnaissance could confirm whether an entire French army was south of the Sambre. Moreover, he wanted at all cost to maintain contact with his left wing (Max von Hausen’s Third Army) and his right wing (Kluck’s First Army) during the advance. Yet his corps commanders were chomping at the bit. After some indecision concerning Bülow’s intentions, Arnold von Winckler decided to storm the bridges at Auvelais and Jemeppe-sur-Sambre with his 2d Guard Division (GD). Farther to the west, Max Hofmann’s 19th ID of Emmich’s X Corps likewise took the bridges at Tergné. With two bridgeheads secured against repeated French counterattacks, the Germans were ready to advance against Lanrezac’s main force the next day.

General von Bülow hurled three corps against French Fifth Army on 22 August—only to discover that the French had preempted him with an attack of their own. At his headquarters at Chimay, thirty kilometers from the front, Lanrezac at first had become incapacitated, mulling over his options. He neither approved nor disapproved a suggestion from the commanders of III and X corps to counterattack and retake the lost bridges. Without orders, Sauret and Defforges charged the German positions in the early-hour mists of 22 August, flags unfurled, bugles blaring, bayonets fixed—and without artillery support. Both attacks were brutally beaten back around Arsimont with “staggering losses.” Tenth Corps’ desperate bayonet charges were mowed down by the machine guns of the Prussian Guard; those of III Corps ran headlong into a fierce assault by Emmich’s X Corps.

25

The fields were littered with six thousand French dead and wounded; the roads soon clogged with thousands of Belgian civilians fleeing the deadly mayhem.

In fact, a bloody and confused melee (what military theorists call a “battle of encounter”) quickly developed in

le borinage

. All along the Sambre, a ragged, unplanned series of battles ensued. By late afternoon, Lanrezac’s center had collapsed, with two corps retreating at great loss of life; by nightfall, nine divisions of French III and X corps had been driven ten kilometers back from the Sambre at Charleroi by a mere three divisions of German X Corps and Guard Corps. The entire center and right of French Fifth Army seemed on the point of collapse. On the French left near Fontaine, two divisions of Einem’s VII Corps hurled Sordet’s cavalry corps back across the Sambre, exposing the right flank of the late-arriving BEF at Mons. At 8:30

PM

, Lanrezac informed Joffre of the day’s “violent” events. “Defforges’ X Corps suffered badly. … Large numbers of officers

hors de combat

. 3rd Corps and its 5th Division heavily engaged before Chatelet. … The Cavalry Corps, extremely fatigued, no longer in contact with l’armée W[ilson]”

26

—that is, with the British.

That night, Lanrezac again considered his options. He decided to resume the offensive on 23 August. Perhaps he could strike Bülow’s Second Army in the flank from the east. Thus, he shifted Franchet d’Espèrey’s I Corps on the right north toward Namur and ordered Fourth Army to advance on the Meuse. But before Lanrezac could mount his offensive with Fifth Army, a series of disastrous reports from the fronts arrived at Chimay: Fortress Namur had capitulated; French Third and Fourth armies were heavily engaged in the Ardennes and could not come to his rescue; the BEF had been forced to retreat at Mons; and lead elements of German Third Army had crossed the Meuse at Givet. Lanrezac at once grasped the gravity of the situation. He now faced the dire prospect of Bülow’s ponderous advance from the north being augmented by a flanking attack on both his right rear (German Third Army) and his left front (German First Army). Still, his troops fought valiantly, grudgingly yielding ground. General von Kirchbach reported late on 23 August that his X Reserve Corps had been shattered and would not be able to resume the attack the next day. He need not have worried: At 9:30

PM

, Lanrezac, appreciating that he had suffered a major defeat, ordered a general retreat to the line Givet-Maubeuge, to begin at three o’clock the next morning.

27

Joffre spied therein a decided lack of “offensive spirit,” but Lanrezac’s action likely saved Fifth Army from annihilation.