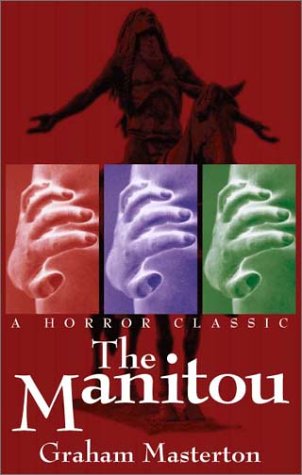

The manitou

The Manitou

by

Graham Masterton

T

he phone bleeped. Without looking up, Dr. Hughes sent his hand

across his desk in search of it. The hand scrabbled through sheaves of paper,

bottles of ink, week-old newspapers and crumpled sandwich packets. It found the

telephone, and picked it up.

Dr. Hughes put

it to his ear. He looked peaky-faced and irritated, like a squirrel trying to

store away its nuts.

“Hughes? This

is McEvoy.”

“Well? I’m

sorry Dr. McEvoy, I’m very busy.”

“I didn’t

meant

to interrupt you in your work, Dr. Hughes. But I have

a patient down here whose condition should interest you.”

Dr. Hughes

sniffed and took off his rimless glasses.

“What kind of

condition?” he asked. “Listen, Dr. McEvoy, it’s very considerate of you to call

me, but I have paperwork as high as a mountain up here, and I really can’t...”

McEvoy wasn’t

put.

off

. “Well, I really think you’ll be interested,

Dr. Hughes. You’re interested in tumors, aren’t you? Well, we’ve got a tumor

down here to end all tumors.”

“What’s so

terrific about it?”

“It’s sited on

the back of the neck. The patient is a female Caucasian, twenty-three years

old. No previous record of tumorous growth, either benign or malignant.”

“And?”

“It’s moving,”

said Dr. McEvoy. “The tumor is actually moving, like there’s something under

the skin that’s alive.”

Dr. Hughes was

doodling flowers with his ballpen. He frowned for a moment,

then

said:

“X-ray?”

“Results in twenty minutes.”

“Palpitation?”

“Feels like any

other tumor. Except that it squirms.”

“Have you tried

lancing it?

Could be just an infection.”

“I’ll wait and

see the X-ray first of all.”

Dr. Hughes

sucked thoughtfully at the end of his pen. His mind flicking back over all the

pages of all the medical books he had ever absorbed, seeking a parallel case,

or a precedent, or even something remotely connected to the idea of a moving

tumor. Maybe he was tired, but somehow he couldn’t seem to slot the idea in

anywhere.

“Dr. Hughes?”

“Yeah, I’m

still here. Listen, what time do you have?”

“Ten after

three.”

“Okay, Dr.

McEvoy. I’ll come down.”

He laid down

the telephone and sat back in his chair and rubbed his eyes. It was St.

Valentine’s Day, and outside in the streets of New York City the temperature

had dropped to fourteen degrees and there was six inches of snow on the ground.

The sky was metallic and

overcast,

and the traffic

crept about on muffled wheels. From the eighteenth story of the Sisters of

Jerusalem Hospital, the city had a weird and luminous quality that he’d never

seen before. It was like being on the moon, thought Dr. Hughes.

Or the end of the world.

Or the Ice Age.

There was

trouble with the heating system, and he had left his overcoat on. He sat there

under the puddle of light from his desk-lamp, an exhausted young man of thirty-three,

with a nose as sharp and pointy as a scalpel, and a scruffy shock of dark brown

hair. He looked more like a teenage auto mechanic than a national expert on

malignant tumors.

His office door

swung open and a plump, white-haired lady with upswept red spectacles came in,

bearing a sheaf of paper and a cup of coffee.

“Just a little more paperwork, Dr. Hughes.

And I thought

you’d like something to warm you up.”

“Thank you,

Mary.” He opened the new file that she had brought him, and sniffed more

persistently. “Jesus, have you seen this stuff? I’m supposed to be a

consultant, not a filing clerk.

Listen, take

this back and dump it on Dr. Ridgeway. He likes paper. He likes it better than

flesh and blood.”

Mary shrugged.

“Dr. Ridgeway sent it to you.”

Dr. Hughes

stood up. In his overcoat, he looked like Charlie Chaplin in The Gold Rush. He

waved the file around in exasperation, and it knocked over his single

Valentine’s card, which he knew had been sent by his mother.

“Oh... Okay.

I’ll have a look at it later. I’m going down to see Dr. McEvoy. He has a

patient he wants me to look at.”

“Will you be

long, Dr. Hughes?” asked Mary. “You have a meeting at four-thirty.”

Dr. Hughes

stared at her wearily, as though he was wondering who she was.

“Long? No, I

don’t think so.

Just as long as it takes.”

He stepped out

of his office into the neon-lit corridor. The Sisters of Jerusalem was an

expensive private hospital, and never smelled of anything as functional as

carbolic and chloroform. The corridors were carpeted in thick red plush, and

there were fresh-cut flowers at every corner. It was more like the kind of

hotel where middle-aged executives take their secretaries for a weekend of

strenuous sin.

Dr. Hughes

called an elevator and sank to the fifteenth floor. He stared at himself in the

elevator mirror, and he considered he was looking

more sick

than some of his patients. Perhaps he would take a vacation. His mother had

always liked Florida, or maybe they could visit his sister in San Diego.

He went through

two sets of swing doors, and into Dr. McEvoy’s office. Dr. McEvoy was a short,

heavy-built man whose white coats were always far too tight under his arms. He

looked like a surgical sausage. His face was big and moonlike and speckled, with

a snub little Irish nose.

He had once

played football for the hospital team, until he had fractured his kneecap in a

violent tackle. Nowadays, he walked with a slightly over-dramatized limp.

“Glad you came

down,” he smiled. “This really is very peculiar, and I know you’re the world’s

greatest expert.”

“Hardly,” said

Dr. Hughes. “But thanks for the compliment.”

Dr. McEvoy

stuck his finger in his ear and screwed it around with great thoughtfulness and

care.

‘The X-rays

will be here in five or ten minutes.

Meanwhile.

I

can’t think what else I can do.”

“Can you show

me the patient?” asked Dr. Hughes.

“Of course.

She’s in my waiting room. I should take your

overcoat off if I were you. She might think I brought you in off the street.”

Dr. Hughes hung

up his shapeless black coat, and then followed Dr. McEvoy through to the

brightly lit waiting room. There were armchairs and magazines and flowers, and

a fish tank full of bright tropical fish. Through the venetian blinds, Dr.

Hughes could see the odd metallic radiance of the afternoon snow.

In a corner of

the room, reading a copy of

Sunset,

was a slim

dark-haired girl. She had a squarish, delicate face – a bit like an imp,

thought Dr. Hughes. She was wearing a plain coffee-colored dress that made her

cheeks look rather sallow. The only clue to her nervousness was an ashtray

crammed with cigarette butts, and a haze of smoke in the air.

“Miss Tandy,”

said Dr. McEvoy, “this is Dr. Hughes. Dr. Hughes is an expert on conditions of

your kind, and he would just like to take a look at you and ask you a few

questions.”

Miss Tandy laid

aside her magazine and smiled. “Sure,” she said, in a distinctive New England

accent. Good family, thought Dr. Hughes. He didn’t have to guess if she was

wealthy or not.

You just didn’t

seek treatment at the Sisters of Jerusalem Hospital unless you had more cash

than you could

raise

off the floor.

“Lean forward,”

said Dr. Hughes. Miss Tandy bent over, and Dr. Hughes lifted the hair at the

back of her neck.

Right in the

hollow of her neck was a smooth round bulge, about the size and shape of a

glass paperweight. Dr. Hughes ran his fingers over it, and it seemed to have

the normal texture of a benign fibrous growth.

“How long have

you had this?” he asked.

“Two or three

days,” said Miss Tandy. “I made an appointment as soon as it started to grow. I

was frightened it was – well, cancer or something.”

Dr. Hughes

looked across at Dr. McEvoy and frowned.

“Two or three days?

Are you sure?”

“Exactly,” said

Miss Tandy. “Today is Friday, isn’t it? Well, I first felt it when I woke up on

Tuesday morning.”

Dr. Hughes

squeezed the tumor gently in his hand. It was firm, and hard, but he couldn’t

detect any movement.

“Does that

hurt?” he asked.

“There’s a kind

of a prickling sensation. But that’s about all.”

Dr. McEvoy

said: “She felt the same thing when I squeezed it.”

Dr. Hughes let

Miss Tandy’s hair fall back, and told her she could sit up straight again. He

pulled up an armchair, and found a tatty scrap of paper in his pocket, and

started to jot down a few notes as he talked to her.

“How big was

the tumor when you first noticed it?”

“Very small.

About the size of a butter-bean, I guess.”

“Did it grow

all the

time,

or only at special times?”

“It only seems

to grow at night. I mean, every morning I wake up and it’s bigger.”

Dr. Hughes made

a detailed squiggle on his piece of paper.

“Can you feel

it normally? I mean, can you feel it now?”

“It doesn’t

seem to be any worse than any other kind of bump. But sometimes I get the

feeling that it’s shifting.”

The girl’s eyes

were dark, and there was more fear in them than her voice was giving away.

“Well,” she

said slowly. “It’s almost like somebody trying to get comfortable in bed. You

know – sort of shifting around, and then lying still.”

“How often does

this happen?”

She looked

worried. She could sense the bafflement in Dr. Hughes, and that worried her.

“I don’t know.

Maybe four or five times a day.”

Dr. Hughes made

some more notes and chewed his lip.

“Miss Tandy,

have you noticed any changes in your own personal condition of health over the

past few days – since you’ve had this tumor?”

“Only a little tiredness.

I guess I don’t sleep too well at

night. But I haven’t lost any weight or anything like that.”

“Hmm.”

Dr. Hughes wrote some more and looked for a while at

what he’d written. “How much do you smoke?”

“Usually only

half a pack a day. I’m not a great smoker. I’m just nervous right now, I

guess.”

Dr. McEvoy

said: “She had a chest X-ray not long ago. She had a clean bill of health.”

Dr. Hughes

said: “Miss Tandy, do you live alone? Where do you live?”

“I’m staying

with my aunt on

Eighty-second

Street. I’m working for

a record company, as a personal assistant. I wanted to find an apartment of my

own, but my parents thought it would be a good idea if I lived with my aunt for

a while. She’s sixty-two. She’s a wonderful old lady. We get along together

just fine.”

Dr. Hughes

lowered his head. “Don’t get me wrong when I ask this, Miss Tandy, but I think

you’ll understand why I have to. Is your aunt in a good state of health, and is

the apartment clean? There’s no health risk there, like cockroaches or blocked

drains or food dirt?”

Miss Tandy

almost grinned, for the first time since Dr. Hughes had seen her. “My aunt is a

wealthy woman, Dr. Hughes. She has a full-time cleaner, and a maid to help with

the cooking and entertaining.”

Dr. Hughes

nodded. “Okay, we’ll leave it like that for now. Let’s go and chase up those

X-rays, Dr. McEvoy.”

They went back

into Dr. McEvoy’s office and sat down. Dr. McEvoy took out a stick of chewing

gum and bent it between his teeth.

“What do you

make of it, Dr. Hughes?”

Dr. Hughes

sighed. “At the moment, I don’t make anything at all. This bump came up in two

or three days and I’ve never come across a tumor that did that before. Then

there’s this sensation of movement. Have you felt it move yourself?”

“Sure,” said

Dr. McEvoy. “Just a slight shifting, like there was something under there.”

“That may be

caused by movements of the neck. But we can’t really tell until we see the

X-rays.”

They sat in

silence for a few minutes, with the noises of the hospital leaking faintly from

the building all around them. Dr. Hughes felt cold and weary, and wondered when

he was going to get home. He had been up until two a.m. last night, dealing

with files and statistics, and it looked as though he was going to be just as

late tonight. He sniffed, and stared at his scuffy brown shoe on the carpet.

After five or

six minutes, the office door opened and the radiologist came in with a large brown

envelope. She was a tall

negress

with short-cut hair

and no sense of humor at all.