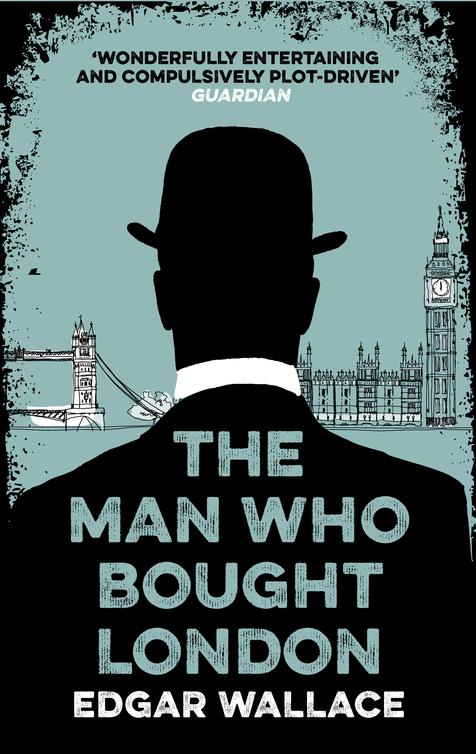

The Man Who Bought London

Read The Man Who Bought London Online

Authors: Edgar Wallace

WHO BOUGHT

LONDON

EDGAR WALLACE

- Title Page

- CHAPTER I

- CHAPTER II

- CHAPTER III

- CHAPTER IV

- CHAPTER V

- CHAPTER VI

- CHAPTER VII

- CHAPTER VIII

- CHAPTER IX

- CHAPTER X

- CHAPTER XI

- CHAPTER XII

- CHAPTER XIII

- CHAPTER XIV

- CHAPTER XV

- CHAPTER XVI

- CHAPTER XVII

- CHAPTER XVIII

- CHAPTER XIX

- CHAPTER XX

- CHAPTER XXI

- CHAPTER XXII

- CHAPTER XXIII

- CHAPTER XXIV

- CHAPTER XXV

- CHAPTER XXVI

- CHAPTER XXVII

- CHAPTER XXVIII

- CHAPTER XXIX

- CHAPTER XXX

- BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

- HESPERUS PRESS

- SELECTED TITLES FROM HESPERUS PRESS

- Copyright

Night had come to the West End, but though the hour was late, though all Suburbia might at this moment be wrapped in gloom – a veritable desert of deadness relieved only by the brightness and animation of the busy public-houses – the Strand was thronged with a languid crowd all agape for the shady mysteries of the night world, which writers describe so convincingly, but the evidence of which is so often disappointing.

Deserted Suburbia had sent its quota to stare at the evil nightlife of the Metropolis. That it was evil none doubted. These pallid shop girls clinging to the arms of their protecting swains, these sedate, married ladies, arm in arm with their husbands, these gay young bloods from a thousand homes beyond the radius – they all knew the significance of those two words: ‘West End’.

They stood for an extravagant aristocracy – you could see the shimmer and sheen of them as they bowled noiselessly along the Strand from theatre to supper table, in their brilliantly illuminated cars, all lacquer and silver work. They stood for all the dazzle of light, for all the joyous ripple of laughter, for the faint strains of music which came from the restaurants.

Suburbia saw, disapproved, but was intensely interested. For here was hourly proof of unthinkable sums that to the strolling pedestrians were only reminiscent of the impossible exercises in arithmetic which they had been set in their earlier youth. It all reeked of money – the Strand – Pall Mall (all ponderous and pompous clubs), but most of all, Piccadilly Circus, a great glittering diamond of light set in the golden heart of London.

Money – money – money! The contents bills reflected the spirit of the West. ‘Well-known actress loses 20,000 pounds’ worth of jewellery,’ said one; ‘Five million shipping deal,’ said another, but that which attracted most attention was the naming bill which

The Monitor

had issued –

KING KERRY TO BUY LONDON

(Special)

It drew reluctant coppers from pockets which seldom knew any other variety of coinage than copper. It brought rapidly walking men, hardened to the beguilement of the contents-bill author, to a sudden standstill.

It even lured the rich to satisfy their curiosity. ‘King Kerry is going to buy London,’ said one man.

‘I wish he’d buy this restaurant and burn it,’ grumbled the other, rapping on the table with the handle of a fork. ‘Waiter, how long are you going to keep me before you take my order?’

‘In a moment, sir.’

A tall, good-looking man sitting at the next table, and occupying at the moment the waiter’s full attention, smiled as he heard the conversation. His grey hair made him look much older than he was, a fact which afforded him very little distress, for he had passed the stage when his personal appearance excited much interest in his own mind. There were many eyes turned toward him, as, having paid his bill, he rose from his chair.

He seemed unaware of the attention he drew to himself, or, if aware, to be uncaring, and with a thin cigar between his even white teeth he made his way through the crowded room to the vestibule of the restaurant.

‘By Jove,’ said the man who had complained about the waiter’s inattention, ‘there goes the chap himself!’ and he twisted round in his chair to view the departing figure.

‘Who?’ asked his friend, laying down the paper he had been reading.

‘King Kerry,’ said the other, ‘the American millionaire.’

King Kerry strolled out through the revolving doors and was swallowed up with the crowd.

Following King Kerry, at a distance, was another well-dressed man, younger than the millionaire, with a handsome face and a subtle air of refinement.

He scowled at the figure ahead as though he bore him no good will, but made no attempt to overtake or pass the man in front, seeming content to keep his distance. King Kerry crossed to the Haymarket and walked down that sloping thoroughfare to Cockspur Street.

The man who followed was slimmer of build, yet well made. He walked with a curious restricted motion that was almost mincing. He lacked the swing of shoulder which one usually associated with the well-built man, and there was a certain stiffness in his walk which suggested a military training. Reflected by the light of a lamp under which he stopped when the figure in front slowed down, the face was a perfect one, small featured and delicate.

Hermann Zeberlieff had many of the characteristics of his Polish-Hungarian ancestry and if he had combined with these the hauteur of his aristocratic forebears, it was not unnatural, remembering that the Zeberlieffs had played no small part in the making of history.

King Kerry was taking a mild constitutional before returning to his Chelsea house to sleep. His shadower guessed this, and

when King Kerry turned on to the Thames Embankment, the other kept on the opposite side of the broad avenue, for he had no wish to meet his quarry face to face.

The Embankment was deserted save for the few poor souls who gravitated hither in the hope of meeting a charitable miracle.

King Kerry stopped now and again to speak to one or another of the wrecks who ambled along the broad pavement, and his hand went from pocket to outstretched palm not once but many times.

There were some who, slinking towards him with open palms, whined their needs, but he was too experienced a man not to be able to distinguish between misfortune and mendicancy.

One such a beggar approached him near Cleopatra’s Needle, but as King Kerry passed on without taking any notice of him, the outcast commenced to hurl a curse at him. Suddenly King Kerry turned back and the beggar shrunk towards the parapet as if expecting a blow, but the pedestrian was not hostile. He stood straining his eyes in the darkness, which was made the more baffling because of the gleams of distant lights, and his cigar glowed red and grey.

‘What did you say?’ he asked gently. ‘I’m afraid I was thinking of something else when you spoke.’

‘Give a poor feller creature a copper to get a night’s lodgin’!’ whined the man. He was a bundle of rags, and his long hair and bushy beard were repulsive even in the light which the remote electric standards afforded.

‘Give a copper to get a night’s lodging?’ repeated the other.

‘An’ the price of a dri– of a cup of coffee,’ added the man eagerly.

‘Why?’

The question staggered the night wanderer, and he was silent for a moment.

‘Why should I give you the price of a night’s lodging – or give you anything at all which you have not earned?’

There was nothing harsh in the tone: it was gentle and friendly, and the man took heart.

‘Because you’ve got it an’ I ain’t,’ he said – to him a convincing and unanswerable argument.

The gentleman shook his head.

‘That is no reason,’ he said. ‘How long is it since you did any work?’

The man hesitated. There was authority in the voice, despite its mildness. He might be a ‘split’ – and it would not pay to lie to one of those busy fellows.

‘I’ve worked orf an’ on,’ he said sullenly. ‘I can’t get work what with foreyners takin’ the bread out of me mouth an’ undersellin’ us.’

It was an old argument, and one which he had found profitable, particularly with a certain type of philanthropist.

‘Have you ever done a week’s work in your life, my brother?’ asked the gentleman.

One of the ‘my brother’ sort, thought the tramp, and drew from his armoury the necessary weapons for the attack.

‘Well, sir,’ he said meekly, ‘the Lord has laid a grievous affliction on me head –’

The gentleman shook his head again.

‘There is no use in the world for you, my friend,’ he said softly. ‘You occupy the place and breathe the air which might be better employed. You’re the sort that absorbs everything and grows nothing: you live on the charity of working people who cannot afford to give you the hard-earned pence your misery evokes.’

‘Are you goin’ to allow a feller creature to walk about all night?’ demanded the tramp aggressively.

‘I have nothing to do with it, my brother,’ said the other coolly. ‘If I had the ordering of things I should not let you walk about.’

‘Very well, then,’ began the beggar, a little appeased.

‘I should treat you in exactly the same way as I should treat any other stray dog – I should put you out of the world.’

And he turned to walk on.

The tramp hesitated for a moment, black rage in his heart. The Embankment was deserted – there was no sign of a policeman.

‘Here!’ he said roughly, and gripped King Kerry’s arm.

Only for a second, then a hand like teak struck him under the jaw, and he went blundering into the roadway, striving to regain his balance.

Dazed and shaken he stood on the kerb watching the leisurely disappearance of his assailant. Perhaps if he followed and made a row the stranger would give him a shilling to avoid the publicity of the courts; but then the tramp was as anxious as the stranger, probably more anxious, to avoid publicity. To do him justice, he had not allowed his beard to grow or refrained from cutting his hair because he wished to resemble an anchorite, there was another reason. He would like to get even with the man who had struck him – but there were risks.

‘You made a mistake, didn’t you?’

The beggar turned with a snarl.

At his elbow stood Hermann Zeberlieff, King Kerry’s shadower, who had been an interested spectator of all that had happened.

‘You mind your own business!’ growled the beggar, and would have slouched on his way.

‘Wait a moment!’ The young man stepped in his path. His hand went into his pocket, and when he withdrew it he had a little handful of gold and silver. He shook it; it jingled musically.

‘What would you do for a tenner?’ he asked.

The man’s wolf eyes were glued to the money.

‘Anything,’ he whispered, ‘anything, bar murder.’

‘What would you do for fifty?’ asked the young man.

‘I’d – I’d do most anything,’ croaked the tramp hoarsely.

‘For five hundred and a free passage to Australia?’ suggested the young man, and his piercing eyes were fixed on the beggar.

‘Anything – anything!’ almost howled the man.

The young man nodded.

‘Follow me,’ he said, ‘on the other side of the road.’

They had not been gone more than ten minutes when two men came briskly from the direction of Westminster. They stopped every now and again to flash the light of an electric lamp upon the human wreckage which lolled in every conceivable attitude of slumber upon the seats of the Embankment. Nor were they content with this, for they scrutinized every passer-by – very few at this hour in the morning.

They met a leisurely gentleman strolling toward them, and put a question to him.

‘Yes,’ said he, ‘curiously enough I have just spoken with him – a man of medium height, who spoke with a queer accent. I guess you think I speak with a queer accent too,’ he smiled, ‘but this was a provincial, I reckon.’

‘That’s the man, inspector,’ said one of the two, turning to the other. ‘Did he have a trick when speaking of putting his head on one side?’

The gentleman nodded.

‘Might I ask if he is wanted – I gather that you are police officers?’

The man addressed hesitated and looked to his superior.

‘Yes, sir,’ said the inspector. ‘There’s no harm in telling you that his name is Horace Baggin, and he’s wanted for murder – killed a warder of Devizes Gaol and escaped whilst serving the first portion of a lifer for manslaughter. We had word that he’s been seen about here.’

They passed on with a salute, and King Kerry, for it was he, continued his stroll thoughtfully.

‘What a man for Hermann Zeberlieff to find?’ he thought, and it was a coincidence that at that precise moment the effeminate-looking Zeberlieff was entertaining an unsavoury tramp in his Park Lane study, plying him with a particularly villainous kind of vodka; and the tramp, with his bearded head on one side as he listened, was learning more about the pernicious ways of American millionaires than he had ever dreamt.

‘Off the earth fellers like that ought to be,’ he said thickly. ‘Give me a chance – hit me on the jaw, he did, the swine – I’ll millionaire him!’

‘Have another drink,’ said Zeberlieff.