The Mammoth Book of Conspiracies (73 page)

Read The Mammoth Book of Conspiracies Online

Authors: Jon E. Lewis

Tags: #Social Science, #Conspiracy Theories

We do not have to demonstrate an intent to discriminate. We do not have to demonstrate that there was some kind of conspiracy against minorities or that anyone involved in the administration of elections today or yesterday had any intent whatever to discriminate against minorities, because indeed under the Voting Rights Act, practices can be illegal so long as they have the effect of diminishing minority opportunities to participate fully in the political process and elect candidates of their choice.

Professor Lichtman testified that a violation occurs if the following two criteria are satisfied:

• | if there are “differences in voting procedures and voting technologies between white areas and minority areas”; and |

• | if voting procedures and voting technologies used in minority areas “give minorities less of an opportunity to have their votes counted.” |

Referring to a

New York Times

study showing that voting systems in Florida’s poorer, predominantly minority areas are less likely to allow a voter to cast a properly tallied ballot, Professor Lichtman testified:

In other words, minorities perhaps can go to the polls unimpeded, but their votes are less likely to count because of the disparate technology than are the votes of whites … That is the very thing the Voting Rights Act was trying to avoid – that for whatever reason and whatever the intent, the Voting Rights Act is trying to avoid different treatment of whites and minorities when it comes to having one’s vote counted … If your vote isn’t being tallied, that in effect is like having your franchise denied fundamentally.

Professor Lichtman testified that one remedy in such a case would be to equalize the technology across all voting places in the state of Florida – “to have technologies equalized such that there are no systematic correlations between technologies and whites and minorities, and a minority vote is as likely to be tallied as a white vote.” The professor acknowledged this would require spending additional funds in certain parts of the state.

Darryl Paulson testified he did not believe

intentional

discrimination occurred in Florida against people of color during the 2000 vote – meaning “some sort of collusion among public officials, some sort of agreement in principle, some sort of mechanism to impose” discrimination. However, Professor Paulson agreed with Professor Lichtman on the voter spoilage issue, testifying that the “real scandal” in Florida was “the inequities that existed from county to county. Disparities between wealthy and poor counties were reflected in the types of voting machinery used. Poor counties, whether in Florida or elsewhere, have always had a disproportionate number of votes not counted.”

Spoiled Ballots

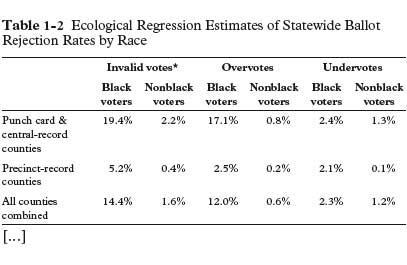

An analysis of the incidence of spoiled ballots (votes cast but not counted) shows a correlation between the number of registered African American voters and the rate at which ballots were spoiled. The higher the percentage of African American residents and of African American voters, the higher the chance of the vote being spoiled.

[...]

In a very small part, the county-level relationship between race and rates of ballot rejection can be attributed to the fact that a greater percentage of African American registered voters live in counties with technologies that produce the greatest rates of rejected ballots. About 70 percent of African American registrants resided in counties using technology with the highest ballot rejection rates – punch cards and optical scan systems recorded centrally – compared with 64 percent of non-African American registrants. Counties using punch card or optical scan methods recorded centrally rejected about 4 percent of all ballots cast, compared with about 0.8 percent for counties using optical scan methods recorded by precinct. The vast majority of rejected votes were recorded in counties using punch cards or optical scan methods recorded centrally. Such counties included about 162,000 out of 180,000 unrecorded votes in Florida’s 2000 presidential election. These counties that used punch cards or optical scan technology recorded centrally included 65 percent of all ballots cast in Florida’s 2000 presidential election, but 90 percent of rejected ballots.

Impact of the Purge List

A similar effect upon African Americans is presented based on an analysis of the state-mandated purge list. In 1998, the Florida legislature enacted a statute that required the Division of Elections to contract with a private entity to purge its voter file of any deceased persons, duplicate registrants, individuals declared mentally incompetent, and convicted felons without civil rights restoration, i.e., remove ineligible voter registrants from voter registration rolls. What occurred in Miami-Dade County provides a vivid example of the use of these purge lists. According to the supervisor of elections for Miami-Dade County, David Leahy, the state provides his office with a list of convicted felons who have not had their rights restored. It is the responsibility of Mr. Leahy’s office to verify such information and remove those individuals from the voter rolls “[i]f the supervisor

does not

determine that the information provided by the division is

incorrect

…” In practice, this places the burden on voters to prove that they are incorrectly placed on the purge list. Mr. Leahy’s office sends a notice to the individuals requiring them to inform the office if they were improperly placed on the list.

Many people appear on the list incorrectly. For example, in the 2000 election, the supervisor of elections office for Miami-Dade received two lists – one in June 1999 and another in January 2000 – from which his office identified persons to be removed from the voter rolls. Of the 5,762 persons on the June 1999 list, 327 successfully appealed and, therefore, remained on the voter rolls (see table 1–4, p.517). Another 485 names were later identified as persons who either had their rights restored or who should not have been on the list. Thus at least 14.1 percent of the persons whose names appeared on the Miami-Dade County list appeared on the list in error. Similarly, 13.3 percent of the names on the January 2000 list were eligible to vote. In other words, almost one out of every seven people on this list were there in error and risked being disenfranchised.

In addition to the possibility of persons being placed on the list in error, the use of such lists has a disparate impact on African Americans. African Americans in Florida were more likely to find their names on the list than persons of other races. African Americans represented the majority of persons – over 65 percent – on both the June 1999 and the January 2000 lists (see table 1–4). This percentage far exceeds the African American population of Miami-Dade County, which is only 20.4 percent. Comparatively, 77.6 percent of the persons residing in Miami-Dade County are white; yet whites accounted for only 17.6 percent of the persons on the June 1999 convicted felons list. Hispanics account for only 16.6 percent of the persons on that list, yet comprise 57.4 percent of the population. The proportions of African Americans, whites, and Hispanics on the January 2000 list were similar to the June 1999 list.

This discrepancy between the population and the percentage of persons of color affected by the list indicates that the use of such lists – and the fact that the individuals bear the burden of having their names removed from the list – has a disproportionate impact on African Americans.

Indeed, the persons who successfully appealed to have their names removed from the list provided to Miami-Dade County by the Florida Division of Elections are also disproportionately African American. One hundred fifty-five African Americans (47.4 percent of the total) successfully appealed in response to the June 1999 list, and 84 African Americans (59.2 percent of the total) successfully appealed in response to the January 2000 list. Hispanics accounted for approximately 22 percent of those who appealed in response to both lists. White Americans accounted for 30 percent of those who appealed in 1999 and 26.7 percent of those who appealed in 2000 (see table 1–4). Based on the experience in Miami-Dade County, the most populous county in the state, it appears as if African Americans were more likely than whites and Hispanics to be incorrectly placed on the convicted felons list.

CONCLUSION

The Voting Rights Act prohibits both intentional discrimination and “results” discrimination. It is within the jurisdictional province of the Justice Department to pursue and a court of competent jurisdiction to decide whether the facts prove or disprove illegal discrimination under either standard. The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights does not adjudicate violations of the law. It does not hold trials or determine civil or criminal liability. It is clearly within the mandate of the Commission, however, to find facts that may be used subsequently as a basis for legislative or executive action designed to protect the voting rights of all eligible persons.

Accordingly, the Commission is duty bound to report, without equivocation, that the analysis presented here supports a disturbing impression that Florida’s reliance on a flawed voter exclusion list, combined with the state law placing the burden of removal from the list on the voter, had the result of denying African Americans the right to vote. This analysis also shows that the chance of being placed on this list in error is greater for African Americans. Similarly, the analysis shows a direct correlation between race and having one’s vote discounted as a spoiled ballot. In other words, an African American’s chance of having his or her vote rejected as a spoiled ballot was significantly greater than a white voter’s. Based on the evidence presented to the Commission, there is a strong basis for concluding that section 2 of the VRA was violated.

Chapter 2

First-Hand Accounts of Voter Disenfranchisement

Who are to be the electors of the Federal Representatives? Not the rich more than the poor; not the learned more than the ignorant; not the haughty heirs of distinguished names, more than the humble sons of obscure and unpropitious fortune. The electors are to be the great body of the people of the United States.

Although statistics on spoiled ballots and voter purge lists point to problems in Florida’s election, perhaps the most compelling evidence of election irregularities the Commission heard was the first-hand accounts by citizens who encountered obstacles to voting. The following chapter presents individual accounts of voting system failures.

VOTERS NOT ON THE ROLLS AND UNABLE TO APPEAL

On November 7, 2000, millions of Florida voters arrived at their designated polling places to cast their votes. Unfortunately, countless voters were denied the opportunity to vote because their names did not appear on the lists of registered voters. When poll workers attempted to call the supervisors of elections offices to verify voter registration status, they were often met with continuous busy signals or no answer. In accordance with their training, most poll workers refused to permit persons to vote whose names did not appear on the rolls at their precinct. Thus, numerous Floridians were turned away from the polls on Election Day without being allowed to vote and with no opportunity to appeal the poll workers’ refusal. The following are a few examples of experiences that Floridians had who were turned away from their polling places.

Citizens Who Were Not Permitted to Vote

Other books

Cloud Permutations by Tidhar, Lavie

A Necessary Husband by Debra Mullins

Tempting Gray - Untouchables 02 by T. A. Grey

Eye to Eye: Ashton Ford, Psychic Detective by Don Pendleton

Paladin (Graven Gods 1) by Shelby

Wild Song by Janis Mackay

Styx (Walk Of Shame 2nd Generation #2) by Victoria Ashley

Misbehaving by Tiffany Reisz

The Wild Road by Marjorie M. Liu

In the Shadow of the Gods by Rachel Dunne