The Malice of Fortune (14 page)

Read The Malice of Fortune Online

Authors: Michael Ennis

Tags: #Thrillers, #General, #Historical, #Fiction

I could not help but wonder if he had been here long enough to murder one woman, wait for her charm bag to be delivered to the pope in Rome, and, shortly after the arrival of His Holiness’s emissary, murder another woman in the same brutal yet meticulous fashion.

His lady nodded at me. “That is such a lovely gown,” she said in a sweet, cither-like voice. “One does not see

velluto allucciolati

of that quality these days. You must have had it sewn some years ago.” I stifled a laugh; she already sounded like a jealous wife. Had I wished to set myself after her signore, I could have quickly turned her jealousy to envy, a far more sour vintage.

But I did not need to encourage Signor Oliverotto. He turned to his little

cortigiana

and said, “Play something. Without words.”

Silently the girl took up her

lira da braccio

from the chair next to her, backing away from the table like a waiting lady leaving a duchess. She began to play the

Gelosia

, holding the slender bow between two fingers and her thumb, drawing the taut horsehairs over the strings of her

lira

with the liquid grace of a dancer—although her notes were not so beguiling.

As she played on, her companion turned his attention to a silver plate crowded with miniature olives. Signor Oliverotto’s hands seemed twice as large as most men’s, yet delicately he began to arrange the tiny olives into some pattern, although it was not at once clear what he intended to make. He did not look up until he had finished his

disegno

, whereupon the ferocity of his stare so startled me that I could not observe what he had created. “She will learn,” he said to me, his tone far more gentle than his eyes. “The

lira

, like warfare, requires long practice,

while one is still young. She can benefit from instruction.” Here he cocked his head, as he had the previous night on the drawbridge. “But I would have no need to teach you, would I?”

Signor Oliverotto smiled thinly and edged his platter of olives toward me. Having made this offering, he rose and left me with a short salute, touching his fingers to his velvet cap. When he collected his girl, he took her arm so quickly that her delicate bow screeched against the strings.

Only when they had gone did I look down at the platter of olives. Signor Oliverotto had made a perfect spiral.

I waited an hour for Messer Agapito to return, whereupon he instructed me I would have to wait some more, before he disappeared again. As the night wore on, the ambassadors were summoned, separately, each to a lengthy audience. Ramiro da Lorca also came and went, in a fury of clicking boots, his dark complexion nearly brick-colored; he was not required to wait at all and his meeting with the duke was similarly brief. He passed me with hardly a glance, though surely he knew I was the same notorious woman whose house he had so thoroughly searched the day after Juan’s murder.

At last Agapito came back down the stairs, for a moment standing silently over me like a priest at Mass, as if offering me the absolution of a prudent exit. “His Excellency is ready for you.”

The light in the stairway was provided by a large candelabrum; I found this peculiar, since a little oil lamp would have sufficiently illuminated the steps. Agapito knocked on the lone door in the landing, then opened it quickly himself. A woman slipped out like a wraith. She wore a snow-white chemise, her nipples making dark points beneath the thin fabric—I thought due to the cold, until I saw her eyes.

I knew the expression there, though it is a rare thing in my experience, because most ladies in my former business guard themselves well; if not, they are soon lost. And this lady

was

lost, as if upon a vast sea, entirely without stars or instruments to guide her, searching only for the touch of the man she had just left. There is a terrible bondage in such eyes, and always fear.

Even so, in such a state there is also a profound abandonment to one’s senses, and this I saw in her mouth, the subtle yet swollen pendant of her lower lip, the flesh above her thinner upper lip still moist with sweat.

Only when I observed that her hair was as blond as mine had been five years previously did I draw away from her with a start, for a moment imagining I had just encountered the duke’s sister, Lucrezia, now the Duchess of Ferrara. I was all the more startled because I so firmly believed that despite all the scurrilous gossip that Valentino was Lucrezia’s lover—the same had been said of Juan and the pope himself—there was no truth to these rumors.

But I could not see the rest of the lady’s face, which was concealed by a birdlike Carnival mask. She kept her eyes on me, turning her head even as she passed, though not as if I were a rival. Instead she seemed to acknowledge some kinship of our souls.

When I entered the dim room, however, it was as if she had been a phantom. Duke Valentino sat behind a single table in a large study that was otherwise unfurnished, poring over some document by the light of a single reflecting lamp, his jacket laced nearly to his chin. The tabletop was covered with stacks of papers.

Valentino pushed away the bronze lamp and sat back, clasping his gloved hands over his breast. He was attired entirely in black, his long, grave face appearing almost to float. He examined me, a silent attention I found considerably unsettling; at best, I expected a grim warning to remain in my rooms until I was sent back to Rome. And I did not want to consider the worst.

“Let me show you something that Maestro Leonardo has drawn.”

I knew at once that Leonardo had been to see him while I waited in “Paradise”; no doubt there were several passages to this room. Even as I considered this, I observed a small door in the wall behind him.

Valentino sprang from his chair like a hunting panther, yet he came around his table with the same languid grace those animals display when they have been fed and leashed. He looked down and began to thumb through one of the stacks. After a moment he extracted several drawings, which he placed near the lamp. “Come here,” he said. “Look at this.”

It was a study of a man’s arm, in reddish chalk, the contours of the muscles elegantly drawn in a perfect mimicry of life, save that the skin was absent. The myriad veins thus exposed resembled naked trees, the thicker limbs separating into smaller branches and twigs, so to speak.

“Maestro Leonardo has made a number of these studies,” Valentino said. My stomach soured; I wondered if the maestro intended to make similar drawings from the limbs of the butchered women. “Our modern painters have given us a convincing representation of the human form as they believe God created it. But only this maestro shows us the world hidden beneath our flesh. Only in these drawings can we envision man as Nature perfected him, an intricate

invenzione

of tubes and mechanisms.” He circled his finger over the drawing, almost as if he were tracing Signor Oliverotto’s spiral. “Maestro Leonardo already has plans for machines that can mimic Nature in various ways—devices that can walk like a man, or even fly like a bird.”

I had not even begun to digest this ambition, which seemed a challenge to both God and Nature, when Valentino removed this sketch, revealing beneath it a larger drawing, vividly decorated with paint washes upon paper; to my eyes it was some sort of architectural

fantasia

, a plan for a villa or palazzo of fantastical complexity, the bright brick hue contrasted to a thick blue serpentine painted a thumb’s span beneath the fantasy palace, like some immense banner curling in the wind.

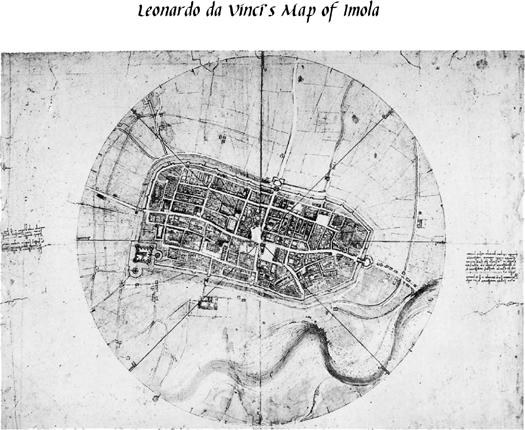

All at once I imagined myself a thousand feet in the air, my shoulders gripped by an eagle’s talons, looking down on the earth, gazing into a walled city—indeed, the very city of Imola I had viewed from the surrounding hills just that day. However, this was Imola as seen by someone with the wings and eyes of a bird, every fortification, residence, and courtyard, each canal and river—for the blue serpent was the Santerno River—in its exact place, but observed from a great height directly above. Now, in my life I have sat upon a cloth-of-gold cushion in a Vatican apartment and held the maps that guided our mariners to the new lands. But I had never seen anything like this.

“Do you see what the maestro has done?” Valentino’s whisper was so faint that I strained to hear him, even in the hush of that room. “Just as he can see within our bodies, so he can also portray the world from a perspective we have never before seen. If we measure this distance on

his map”—he stuck the tip of his finger on the Rocca at the corner of the city, which one could easily distinguish by its circular towers, then pointed to the Piazza Maggiore in the center of the city—“and this distance”—he now moved his finger to the Santerno River, outside the walls—“we will obtain precisely the same proportion that results if we pace the ground itself or measure the actual distance with mechanical devices. Leonardo’s

mappa

is an image of the world identical in all its features, reduced to a scale that we can hold in our hands.”

Yet even as Valentino extolled this extraordinary

mappa

, I could see all too clearly that the novel perspective and uncanny fidelity were not the only remarkable features. The center of the map was also the center of the city, where two ancient Roman roads, the Via Emilia and Via Appia, cross each other. On the map, this intersection was also the hub of a circle, drawn in ink, that surrounded the entire city and the fields outside its walls. Like all geographers, Leonardo had indicated the points of the compass in the form of a wind rose, employing eight lines that proceeded carefully from the center to the perimeter of this circle, dividing it into an octave of evenly spaced slices. Where each line of the wind rose met the rim of the circle, in the fashion of a wheel’s spoke, it was labeled in a small, fine hand:

Septantrione

, this being the north wind;

Greco

, the northeast wind;

Levante

, east wind;

Scirocho

, the southeast wind—and so on around the compass, comprising the eight principal winds.

“This is it, isn’t it?” I said. I put my fingertip on the map, precisely where the compass line labeled

Scirocho

met the circle scribed around the city, just outside a bend in the Santerno River. “I believe this is where one quarter of the first victim was found. Today I saw the cairn of stones the maestro left beside the river.”

Skipping a line each time, in quick sequence I pointed where three other lines of the wind rose also met the circle, as I read the names written alongside them: “

Libecco

,

Maestro

,

Greco

.” Southwest, northwest (this being the strongest, or “master” wind), northeast. “Each point establishes the corner of an imaginary square, which we are able to see through the agency of Maestro Leonardo’s remarkable map. Thus the murderer was able to boast that he had left one quarter of a woman’s body at each corner of the winds. God’s Cross. Whoever has done this had to have seen this

mappa

.”

Of course I presumed that Valentino’s

condottieri

had been privileged to see this map before they betrayed him.

Valentino did not even nod. “But you have not finished,” he said flatly. “Show me the rest.”

Leonardo’s map was so precise that I was able to trace our route that afternoon, from the pile of stones beside the river into the hills south of the city, running my finger directly along the compass line labeled for the south wind,

Mezzodi

. Yet as I attempted to judge the distance on the map in proportion to the distance we had traveled, I understood the flaw in my reasoning: I was forced to move my finger off the map entirely.

“I presumed that he would make another figure of geometry,” I said, “following the points of this map. No doubt this is what Leonardo was measuring this afternoon.” I shook my head. “Unless the

mappa

itself is in error, what we found today”—I lifted my hand and crossed myself—“cannot be placed on this map.”

“The maestro is continuing his measurements.” Here Valentino nodded slightly, as if satisfied that he had just measured the depth of my knowledge—and my ignorance.