The Male Brain (6 page)

Authors: Louann Brizendine

Tags: #Neuroendocrinology, #Sex differences, #Neuropsychology, #Gender Psychology, #Science, #Medical, #Men, #General, #Brain, #Neuroscience, #Psychology Of Men, #Physiology, #Psychology

Scientists have discovered that the teen brain in both sexes is distinctly

different from the preadolescent brain

. The changes that were becoming obvious in Jake were set in motion by his genes and hormones while he was still in utero. Now, with the end of the juvenile pause, it was time for Jake to ramp up his skills for surviving in a man's world. And he was ready and eager, even if his mother wasn't. At this stage, the millions of

little androgen switches

, or receptors, in his brain are hungrily awaiting the arrival of testosterone--king of the male hormones. As the floodgates are flung wide open, the juice of manhood saturates his body and his brain. When my own son turned fourteen and became moody and irritable, I remember thinking, "Oh my God, soon the testosterone will take him over mind, body, and soul."

Although Kate worried that Jake's behavior was extreme, I assured her that he was no different from

many other boys his age

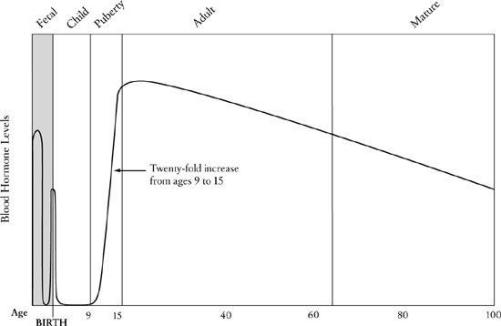

. At fourteen, Jake's brain would have already been under reconstruction for a few years. Between the ages of nine and fifteen, his male brain circuitry, with its billions of neurons and trillions of connections, was "going live" as his testosterone level

soared twentyfold

. If testosterone were beer, a nine-year-old boy would get the equivalent of about one cup a day. But by age fifteen, it would be equal to two

gallons

a day. Jake wasn't into drugs or alcohol. He was loaded on testosterone.

From then on, testosterone would biologically masculinize all the thoughts and behaviors

that emerge from his brain

. It would stimulate the rapid growth of male brain circuits that were formed before he was born. It also would enlarge his testicles, activate the growth of his muscles and bones, make his beard and pubic hair grow, deepen his voice, and

lengthen and thicken his penis

. But just as dramatically, it would make his brain's sexual-pursuit circuits, in his hypothalamus, grow more than twice as large

as those in girls' brains

. The male brain is now structured to push sexual pursuit to

the forefront of his mind

.

Early in puberty, when images of breasts and other female body parts naturally take over their brain's visual cortex, some boys wonder

if they're turning into "pervs."

It takes a little while for them to get used to their new preoccupation with

girls, which runs on autopilot

. This sexual preoccupation is like a large-screen TV in a sports bar--

always on in the background

. When I share this information with teen boys in high-school classrooms, I can see recognition flash across many of their faces, if only for an instant, before they go back to looking bored.

But sex is not the only thing on a teen boy's mind. As the testosterone surged through Jake's brain cells, it was stimulating Together, Jake's brain territorial about his room and sensitive to his peer's putdowns--perceived or real. And when these hormones got mixed with the stress hormone cortisol, they supercharged his body and brain, preparing him for the male fight-or-flight response in reaction to challenges

to his status or turf

. Our brains have been shaped for hundreds of thousands of years by

living in status-conscious hierarchical groups

. And while not all teen boys want to be king of the hill, they do want to be close to the top of the pecking order, staying as far

from the bottom as possible

. And that can mean taking risks

that get them into trouble

.

a companion hormone called vasopressin

.

Like most of us moms, Kate couldn't fully appreciate or relate to all the changes in her teen son's brain. When Dan and Kate came into my office the next week, I said to Kate, "Don't worry. It takes about eight to nine years for the teen brain to complete the remodeling it

began when he entered puberty

. Jake's hormonally enhanced brain circuits will stabilize when he's in his

late teens or early twenties

."

Kate's face fell. "I'm not sure I'll live that long. This boy's killing me." I could see that she was only half joking.

Dan turned to me and said, "Look, Jake's just like every other teenage boy that ever walked the planet Earth. He's gonna look at some porn. He's gonna blow off his homework, get in some fights, and drool over girls. Once he's grounded for a while, he'll come around."

Even though Jake was now grounded until he completed every neglected English assignment, it was still hard for him to focus his brain on schoolwork. If we could watch Jake's brain with a miniature brain scanner as he sat down to do homework, we'd see his prefrontal cortex, or PFC--the area for attention and good judgment--flickering with activity as it tried to force him

to focus on his studies

. We'd also see bursts of vasopressin and testosterone pulsing through his brain, activating

his sex and aggression circuits

. When an image of Dylan's smirking face registered in Jake's brain, his stress

hormone, cortisol, would start climbing

. Now his threat and fear

center--the amygdala--would activate

. And then, as an image of Zoe in that tight sweater she'd been wearing in class today flashed across his secondary visual system, we'd see his sexual circuits activate, distracting him further. Next we'd see his PFC struggling to regain focus on his English homework. But it would be too late. His PFC was no match for his sexual daydreams. Soon, homework would be the last thing on his mind.

Teen boys aren't trying to be difficult. It's just that their brains aren't yet wired to give much thought to the future. Getting boys to study and do homework has always been more of a battle for parents than getting girls to do the same, and with today's high-tech temptations, the battle can feel like a war. Studying instead of doing something fun online just doesn't make sense to teen boys. Research shows that it takes extraordinarily intense sensations to activate the reward centers of the teen boy brain, and

homework just doesn't do it

. Fortunately for Jake, his father came up with both a stick and a carrot--the threat of being grounded without his computer, cell phone, or TV for the next month versus a pair of tickets to a playoff game if he maintained a B average and turned in all his homework. I have to admit I was a little surprised when Jake's grades immediately improved. Somehow Jake took his dad's threat and reward to heart.

I knew that even boys who are getting good grades can begin to hate school by the time they're

in tenth or eleventh grade

. So the next time I met with Jake, I asked him if there was anything at all that he looked forward to at school. He raised his eyebrows as if I must be joking and said, "No. We're not allowed to leave the building or even open our cell phones on campus. It's so stupid. It's like jail." I could see that this was going to be a tough year for Jake and for his parents. Everything about our school system is in direct conflict with teen boys' adventurous, freedom-seeking brains. So we shouldn't be surprised that boys cause 90 percent of the disruptions in the classroom or that 80 percent of

high-school dropouts are boys

. Boys get 70 percent

of the Ds and Fs

. They're smart enough to get good grades, but soon they just don't care. And it doesn't help that school start times are totally out of sync with the teen brain's sleep cycle.

Jake had English class first thing in the morning and said it took everything he had just to stay awake. He said, "I never fall asleep before two in the morning. On weekends I sleep late, but it pisses off my mom."

The sleep clock in a boy's brain begins changing when he's

eleven or twelve years old

. Testosterone receptors reset his brain's clock cells--in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN--so that he stays up later at night and sleeps later in the morning. By the time a boy is fourteen, his new sleep set point is pushed an hour later than that of girls his age. This chronobiological shift is just the beginning of being out of sync with the opposite sex. From now until his female peers go through menopause, he'll go to sleep and wake up later than they do.

Nowadays, most teen boys report getting only five or six hours of sleep on school nights, while their

brains require at least ten

. Some parents have to unplug the Internet if they want their sons to get any sleep at all. If school systems and teachers really wanted teenagers to learn, they'd make start times later by several hours. At least that would increase the chances of a boy's eyes being open--even if it wouldn't wipe the look of boredom from his face.

Like many parents, I used to think teen boys were

acting

bored because it was no longer cool

to be excited about anything

. But scientists have discovered that the pleasure center in the teen boy brain is nearly numb compared with this

area in adults and children

. The reward center in Jake's brain had become less easily activated and wasn't sensitive enough to

feel normal levels of stimulation

. He wasn't acting bored. He

was

bored, and he couldn't help it. When Erin McClure and colleagues at the National Institute of Mental Health scanned teenagers' brains while they looked at shocking pictures of grotesque and mutilated bodies, their brains didn't activate as

much as children's or adults

'. As many high-school teachers know, the teen boy brain needs to be more intensely scared or shocked to become activated even the tiniest bit. The amount of stimulation it takes to make an adult cringe will barely get a rise out of a teen boy. If you want to startle them enough to make them scream or jump, you'll have to magnify the experience with sounds, lights, action, and gore. Now I know why my son liked the bloodiest special effects and shoot-'em-up movies when he was a teen. This preference may not change as boys reach manhood, as blockbuster moviemakers well know. But grown men don't need the same raw rush as they did when they were thrill-seeking teens.

Jake's mom blamed his glazed-over eyes, irritability, and short fuse on lack of sleep, and that definitely had something to do with it. But what she didn't know was that a lot of Jake's anger was being triggered by the new way his male brain was experiencing the world and everyone in it.

If a woman could see the world through "male-colored glasses," she'd be astonished by

how different her outlook would be

. When a boy enters puberty and his body and voice change, his facial expressions also change, and so does the way he

perceives other people's facial expressions

. Blame it on his hormones. A key purpose of a hormone is to prime new behaviors

by modifying our brain's perceptions

. It's testosterone and vasopressin that alter a

teen boy's sense of reality

. In a similar fashion, estrogen and oxytocin change the

way teen girls perceive reality

. The girls' hormonally driven changes in perception prime their brains for emotional connections and relationships, while the boys' hormones prime them

for aggressive and territorial behaviors

. As he reaches manhood, these behaviors will aid him in defending and aggressively protecting his loved ones. But first, he will need to learn how to control these innate impulses.

Over the past year, for no good reason, Jake began to feel much more irritable and angry. He would quickly jump to the conclusion that people he encountered were being hostile toward him. We might ask, Why did it seem the whole world suddenly turned on him? Unbeknownst to Jake, vasopressin was hormonally driving his brain to see the neutral faces of others as unfriendly. Researchers in Maine tested teens' perceptions of neutral faces by giving them a

squirt of vasopressin nasal spray

. They found that, under the influence of this hormone, the teen girls rated neutral faces as more friendly, but the boys rated the neutral faces as more unfriendly or even hostile. This may explain why the next time Jake saw Dylan, he thought his face looked angry when, in fact, Dylan was just bored. Jake's brain was being primed by hormones for getting into trouble.

In animals that are in puberty, scientists have discovered that priming the males' brains with vasopressin and testosterone changes their behavior, too. The scientists found that the brain's two master sensors for emotions--the amygdala and hypothalamus--became supersensitive to

potential threats when hormonally primed

. And in animal studies in which male voles were given vasopressin, it resulted in

more territorial aggression and mate protection

.

In humans, a potential threat is often signaled by a facial expression. Before puberty, when Jake had less testosterone and vasopressin, Dylan's bored face probably wouldn't have looked hostile or angry to him. But now everything was different. Evolutionary biologists believe seeing faces as angrier than they actually are serves an adaptive purpose for males. It allows them to quickly assess whether to fight or to run. At the same time, Jake and Dylan were also honing the ancient male survival skills

of facial posturing and bluffing

. They were learning to hide their emotions. Some scientists believe human males have retained beards and facial hair, even in warmer climates, in order to make them look fierce and hide their true emotions.