The Making Of The British Army (80 page)

Read The Making Of The British Army Online

Authors: Allan Mallinson

The Guards, by definition, have never been part of the line.

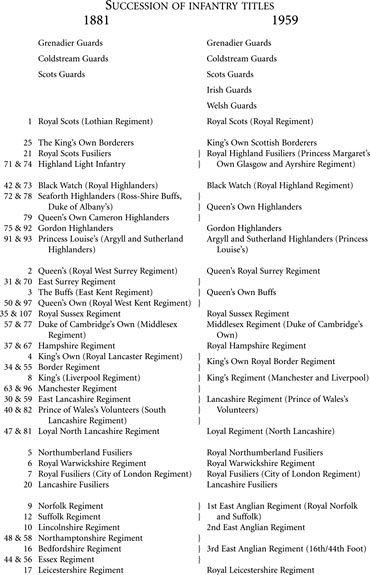

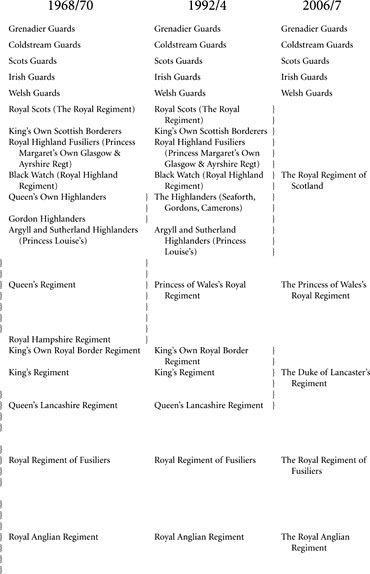

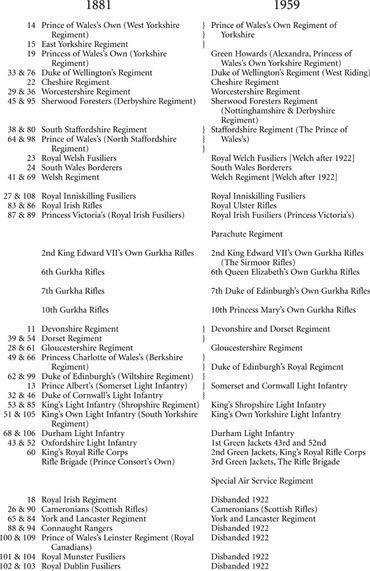

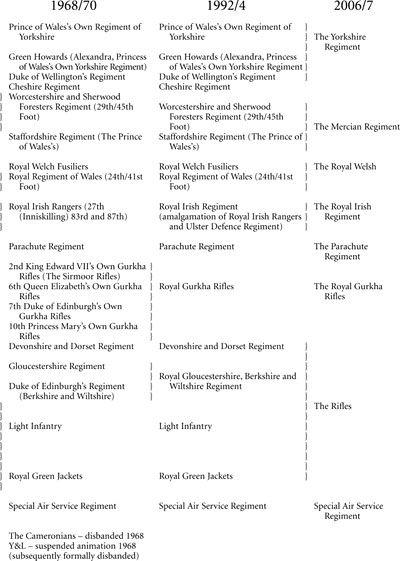

The chart on the following pages sets out what may be called the succession of regiments from the Haldane – Childers reforms to the present day. It will enable the reader whose ancestor served in the infantry during the First World War to see into which present-day regiment his ancestral regiment has been progressively incorporated.

The list is reproduced, with permission, from the website of the Army Museums Ogilby Trust. The trust was founded in 1954 by the late Colonel Robert Ogilby DSO, whose personal experiences in two world wars persuaded him that the fighting spirit of the British soldier stemmed from the

esprit de corps

engendered by the army’s regimental structure. The trust has played, and continues to play, a significant part in the establishment and development of some 136 museums in the United Kingdom, in which this

esprit de corps

is enshrined.

There is scarcely a city or a county town which is not therefore the home of a regimental or a corps museum. And it is in these museums that the real story of the army – the simple devotion of regimental soldiering – is told. A list of these museums, together with information about location, opening times and so much more, can be found at the trust’s website:

www.armymuseums.org.uk

.

Introduction

Professor John McManners, whose thoughts conclude my foreword, was a son of the parsonage. In my Hervey novels I write of officers in the days when commissions were bought and sold – the era of ‘purchase’. In the duke of Wellington’s army they were a reliable ‘officer class’, a branch of the gentry, usually the minor gentry, and the parson’s son was characteristic. But the McManners parsonage was quite different from the characteristic gentry parsonage of my own novels and of Wellington’s army; for Jack McManners’ father, the vicar of West Pelton, had earlier been a Durham miner, a Labour activist and an atheist. In the extract I quote from

Fusilier

(2002), Professor McManners is actually reflecting on an early encounter during his time with the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, at the siege of Tobruk, an encounter which left many Germans dead by his own hand. It caused him not only to conclude what he does of the ultimate reason of the social order, but also to re-examine his faith:

Since that day in Tobruk I had thought through and rationalized the impact of the sudden sight of those slaughtered Germans; what had happened was that Christian belief had become intensely personal. Up to then I had followed, in intellectual debates, the

via eminentia

of Christian apologetics: the order and beauty of creation, the working of laws in the universe, spiritual experience,

show there must be a God. Then, look around for signs of God’s activity in the moral sphere, and we find the story of a good man preaching and healing in Palestine; he is crucified, his followers worship him – but the sight of the dead bodies in the sand-bagged post at Tobruk ended that chain of argument. I had seen what men out of their God-given freedom do to each other. This was the face of evil, and I was part of the evil, being glad, even in revulsion, that they were dead … In face of this, you cannot believe in God, the God of the deists. But you can, almost in despair, turn to the God who suffers with his creation, accepting the burden of sin that arises from human freedom, and taking it on himself. Religious apologetics begin from Jesus on the cross: the Christian life is allegiance to him.

Not everyone will agree with Professor McManners’s conclusions, but his experiences and reflections are nonetheless compelling.

As general references I recommend: the

Oxford

(beautifully)

Illustrated History of the British Army

(1994; revised 2003), edited by the late David Chandler and by Ian Beckett; the Marquess of Anglesey’s multi-volume

History of the British Cavalry

(1973–95), a comprehensive account of the cavalry’s post-Napoleonic experience and development, which tells much of the Victorian army besides; and Anthony Makepeace-Warne’s 1995

Companion to the British Army

(though now out of date on some regimental and technical detail).

For further detailed – if highly selective – reading I have given recommendations below in relation to each chapter or group of chapters.

Chapter 1: Background, and the Civil War

In considering England’s fortuitous geography (from the late thirteenth century the Welsh were no longer a threat), and her lack of a standing army other than a few garrisons in forts up and down the country, it is well to remember that not only was the border with Scotland relatively short (96 miles), it was difficult country to traverse, with few roads, and therefore requiring nothing like so great a frontier garrison as borders on the Continent (nor was Scotland like Austria to France, or Sweden to Prussia; rather more the ‘nuisance neighbour’). The Scottish border was also a considerable distance from anywhere of strategic importance: there was ample time for the county militias to mobilize against an army marching south, and consequently little need of standing forces.

Nevertheless, Englishmen under arms did find themselves on the

Continent from time to time: 100,000 (volunteers from the militia, as well as levies) saw service overseas during the Armada days – some 15 per cent of all able-bodied males out of a population of less than five million. And as a result the nation’s finances were awry for decades. A century and half later the historian Edward Gibbon would write that ‘It has been calculated by the ablest politicians that no State, without being soon exhausted, can maintain above a hundredth part of its members in arms and idleness.’ After the Spanish threat had abated, England maintained scarcely a thousandth part in arms. These men were scattered about the country in little coastal forts, in the great border bastions at Carlisle and Berwick, in barracks in Ireland, and in the field with the Anglo-Dutch brigade to guarantee the frontiers of the newly independent United Provinces (and a Protestant Scheldt estuary, the feared springboard for Spanish invasion). A few Scots units continued in French service too.

For the Civil War in detail there is no more literary a narrative than C. V. Wedgewood’s classic

The King’s War

(1959), which should ideally be read after her equally absorbing

The King’s Peace

(1955). Trevor Royle’s splendid

Civil War

(2004) is likely to remain the best account of the military operations for many a year. Charles (Earl) Spencer’s

Prince Rupert

(2007) is more dashing than the equally authoritative 1996 biography by (General) Frank Kitson, and Lucy Worsley’s

Cavalier

(2007) is both a scholarly and an engrossing account of one of the great families at war (the duke of Newcastle’s). Antonia Fraser’s

Cromwell, Our Chief of Men

(1973) is more engaging than its subject, while John Adamson’s

The Noble Revolt

(2007), though contentious, is quite masterly.

Chapters 2 and 3: The Restoration and ‘Glorious Revolution

’

Parliament’s fear of the King’s using the army to coerce the country – and therefore of martial law – was not irrational, given the continuing and justifiable suspicion of Stuart inclinations to absolutism and Catholicism, and Charles’s predisposition to secret negotiations abroad, especially with his mother’s native France. When his father had declared martial law for the levies raised for the expedition to La Rochelle in 1627, and the countryside began to feel the depredations of billeting and arbitrary military justice, the Commons had petitioned the King, asserting in their Petition of Right that it was ‘wholly and directly contrary to the said laws and statutes of your realm’ to visit

troops and their law on the civil population. Only if the King exercised his suspending power – a true red rag to the parliamentary bull – could martial law be declared, and the army properly discipline its soldiers. Charles II never dared to exercise those powers in England, although he came close to it in the large number of levies raised for the Dutch War in 1673, and the war with France in 1678.

How far Marlborough was influenced by Monck can only be conjecture. Richard Holmes, Marlborough’s most recent biographer, believes that he read one or two classical texts on war, Vegetius almost certainly, but possibly nothing else, for his approach was always pragmatic and showed no sign of any theoretical study, unlike officers in the continental armies. That said, as General Sir Michael Rose has pointed out, in the small world in which the young John Churchill moved he could not have been unaware of Monck’s methods and achievements. Indeed, it seems inconceivable that a young officer on the rise, moving in Court circles – sharing the King’s mistress, indeed – would not hear, or want to hear, the thoughts of Monck, who was, after all, a kingmaker as well as a field soldier. Other than the classical texts and the various medieval treatises there was not yet a great deal to study: Monck’s work was the most up-to-date interpretation of generalship in a modern context that Marlborough could have studied in the 1670s, even without regard to its actual merits (which are considerable). There is therefore every good reason to claim a continuity.