The making of a king (38 page)

Read The making of a king Online

Authors: Ida Ashworth Taylor

Tags: #Louis XIII, King of France, 1601-1643

and was pressing for the important governments of Bordeaux and Chateau-Trompette. The grants of money intended to soften the refusal of posts which, had they passed into his possession, would have strengthened his position to a dangerous degree, did not avail to propitiate him and his party. They therefore withdrew in a body to their several provinces, whence they only returned when the important question of peace or war arose and rendered their presence in Paris necessary.

That question had been raised in consequence of a dispute between Mantua and Savoy, following upon the death of the Duke of Mantua. The Regent took the side of the former, connected with her family, and at one moment it seemed likely that recourse would be had to arms, and that France would be involved in the struggle. Assisting at a Council held for the consideration of the matter, Louis listened to his mother as she gave her voice in favour of a warlike policy and expressed his concurrence.

" Madame," he said, " I am very glad. War must be made."

His hopes were, however, again doomed to disappointment, and, by France at least, the affair was allowed to drop. It must have been plain that her present condition was not one rendering it desirable that she should intervene in foreign quarrels.

CHAPTER XXIII

"

1614

The Prince and his friends leave Paris— Nevers seizes Mezieres— Contrary counsels—Condi's manifesto—Negotiations—Uneasiness at Paris— Louis at the Council-board—Peace signed—Vendome rebellious—The Prince at Poitiers— Court to go to Orleans.

T T must have been clear to the least observant that the continual friction between the Regent and the nobles would not be long in assuming a more acute character ; that open and avowed conflict was not far off, when the smouldering animosity of the Prince and his adherents would burst into flame. The policy hitherto pursued by Marie — " yielding the waves to avoid the shipwreck" — had been a desperate one. It could not, moreover, be carried on for an indefinite period. Posts, honours, money, ad been given as sops to the malcontents, and still they were not satisfied. The Treasury, filled by the economies of Henri-Quatre and Sully, had been emptied, and emptied to no purpose ; it would soon no longer possible to offer bribes of sufficient value o quiet Conde and his partisans. Force would be necessary as a last resort, and the question was who would prove strongest.

In the coming struggle Conde, by position and rank, ould hold the position of leader of those opposed

to the Government. The Regent on the one side, the Princes of the Blood—of whom Conde was for the moment practically the sole representative—on the other—this was the situation ; and an almanack, appearing at the beginning of the year 1614, struck the note of warning. The King's death was predicted, misfortunes were to befall the Queen ; and prosperity awaited the Prince de Conde. The conjunction of the three prophecies was not reassuring. Timid people took alarm. It was not a time when such matters could be treated with contempt ; and the author of the forecasts expiated his imprudence in the galleys. Conde was known to be acquainted with the culprit ; and Louis, having heard of the book, was said to have complained of it bitterly to the Prince.

In the autumn the King's minority would end ; time was therefore short, if his mother were to be coerced and intimidated into acceding to the demands of the opposition. Early in the year, accordingly, the Prince and his adherents decided upon repeating, in an accentuated form, the step by which they were wont to mark their dissatisfaction with the conduct of affairs, and withdrew in a body to the provinces. Conde, Mayenne, and Nevers went first, taking leave of King and Queen with due decorum ; the Prince adding a perfunctory pledge, imposing on no one, that he would return whensoever the King might summon him. Bouillon, left behind to offer an explanation to the Chancellor before following his confederates, used plain language. He told Sillery that the Prince and his friends were forced, by the bad government of the country, to put an end to the ill before it should grow incurable ;

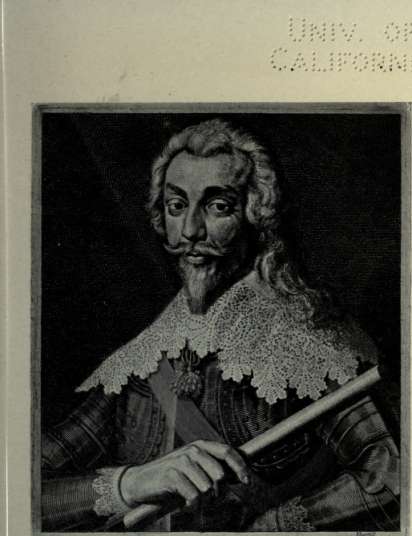

r 1} OYRBON Prmtf dc Conde. DM

From an engraving by Huret.

.296]

HENRY DE BOURBON, Prince de Conde.

Revolt of the Nobles 297

and that Conde had determined to make a representation on the subject to the Regent, and would, with that object, hold an unarmed assembly of those who shared his views, and submit their protest to her. After which, and before he could be arrested, in accordance with the determination arrived at, Bouillon hastened to join his friends. The lad, Longueville, followed ; and lastly Vendome — who had been placed under surveillance at the Louvre, in the expectation that he would not remain behind—escaping from the guard who had him in charge, fled to his government of Brittany, where, supported by the Due de Retz, a local potentate, he set to work to collect troops and to fortify one or two of the strongholds of the province ; writing to the King to recapitulate his grievances and to justify his conduct.

He had been bidden, he said, by the Queen, in Louis's presence not to leave Paris without permission ; had obeyed, but had nevertheless been subsequently made a prisoner. Ten days later God, treating him according to the purity of his intentions, had set him at liberty and, taking him by the hand, had enabled him to reach his own domains, where he found himself threatened with being deprived of his government.

All of which the Duke felt that he had a right to resent.

The next move was made by Nevers, who took forcible possession of the citadel of Mezieres, on the plea of his rights as governor of the province. Overcoming the resistance opposed to him, he sent to inform the Queen of its capture, as though it had been rescued from the enemy ; announcing his purpose of

holding the fortress for the King, and declaring that he was ready to surrender it to any one Louis should appoint.

Notwithstanding his expressions of loyalty and submission, the act could not be interpreted otherwise than as displaying an intention of preparing for a struggle, and when the news reached Paris excitement was great. Marie, seized with panic, had thoughts of resigning the Regency. Some of the Council were in favour of the step, others against it. Amongst these last d'Ancre was naturally prominent. Were power to pass from the Queen he must have known that his day would be over ; and it was determined that she should continue to hold the reins of government.

It had next to be decided whether the rebels should be approached by means of negotiation and diplomacy or resort should be had to arms. Marie spoke of proceeding to Mezieres with troops, of setting forth at once with the King to reduce Nevers to submission. Villeroy and the President Jeannin, who had succeeded Sully in the charge of the finances, were in favour of active measures. Sillery, the Chancellor, advocated conciliation. The Queen, he pointed out, save for the Guises and fipernon, stood almost alone ; the Huguenots were powerful, and, a woman and a child being at the head of affairs, caution was necessary. Supported by the Concini, the Chancellor prevailed.

The Prince, meanwhile, had issued a manifesto justifying his conduct as an attempt to reform the disorders of the kingdom, to be accomplished, if possible, by peaceful methods, recourse to be had to arms solely should that step be necessary in the interests of the King ;

and demanding, in conclusion, that the States-General should be convened. Under these circumstances, the Queen made the grave mistake of parleying with the rebels. It was true that warlike preparations were also in progress; fresh levies of Swiss were made, and the reserves were called out. But, pending the completion of military arrangements—to take effect in case conciliation should fail — de Thou was dispatched to confer with Conde and his partisans, taking leave of the King on March i.

" Go and tell ces messieurs-la to be very good," said the boy, placing his two hands upon the shoulders of the envoy, as he bade him adieu. It would have been better to have taken steps to enforce their good behaviour.

Civil war seemed within measurable distance. The two parties were armed, and were showing every disposition to increase their strength. It was easy for the Princes to use the language of loyalty, to hoist the white flag and cross, and to declare that, if they took up arms, or even went further, it was only to serve the King ; their meaning was well understood, and the fact that the Huguenots appeared to be inclined to give them their support was a dangerous feature of the struggle.

The Regent was taking her measures, and on April 10 the King reviewed in person the two companies of cavalry usually commanded by Nevers, now confided to the more trustworthy hands of Praslin. Paris itself was not considered safe, and orders were issued that when Louis left the palace he should be accompanied by an armed escort. Informed that such was

joo The Making of a King

his mother's command, the boy was manifestly disturbed.

" The Parisians will think that I am afraid," he said. " I am not afraid. I do not fear them "—meaning the confederated nobles. cc If they should come, should we not beat them ? "

" Sire," was the answer,

After some thought, the King bowed to necessity.

" Eien" he said, " but tell them to wear their cloaks over their arms as they pass through the city."

Louis was eager for the resort to force which his mother and her advisers were so anxious to avoid.

Changes were taking place in the conduct of affairs. Louis was beginning to appear at the Council-board. The ministers, as well as the Queen, though they might have been slow to desire his presence there, had awakened