The Magician's Elephant (8 page)

Read The Magician's Elephant Online

Authors: Kate DiCamillo

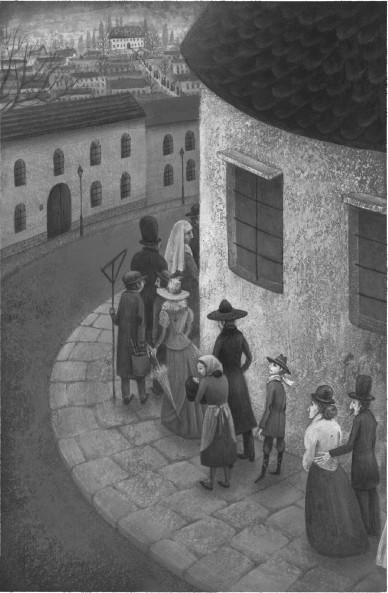

Peter listened carefully, because he would have liked very much to know the actual dimensions of an elephant. It seemed like good information to have; but the man in the black hat never arrived at the point of announcing the figures. Instead, after insisting that he would detail the dimensions, he paused dramatically, took a deep breath and then began again, rocking from heel to toe and saying, “The dimensions of an elephant are most impressive. The dimensions of an elephant are impressive in the extreme…”

The line inched slowly forward, and mercifully, late in the afternoon, the black-hatted man’s mutterings were eclipsed by the music of a beggar who stood singing, his hand outstretched, a black dog at his side.

The beggar’s voice was sweet and gentle and full of hope. Peter closed his eyes and listened. The song placed a steady hand on his heart. It comforted him.

“Look, Adele,” sang the beggar. “Here is your elephant.”

Adele

.

Peter turned his head and looked directly at the beggar, and the man, incredibly, sang her name again.

Adele

“Let him hold her,” his mother had said to the midwife the night that the baby was born, the night that his mother died.

“I do not think I should,” said the midwife. “He is too young himself.”

“No, let him hold her,” his mother said. And so the midwife gave him the crying baby. And he held her.

“This is what you must remember,” said his mother. “She is your sister, and her name is Adele. She belongs to you, and you belong to her. That is what you must remember. Can you do that?”

Peter nodded.

“You will take care of her?”

Peter nodded again.

“Can you promise me, Peter?”

“Yes,” he said, and then he said that terrible, wonderful word once more, in case his mother had not heard him. “Yes.”

And Adele, as if she had heard and understood him too, stopped crying.

Peter opened his eyes. The beggar was gone, and from ahead of him in line came the now achingly familiar words: “The dimensions of an elephant…”

Peter took off his hat and put it back on again and then took it off, working hard at keeping the tears inside.

He had promised.

He had

promised

.

He received a shove from behind.

“Are you juggling your hat, or are you waiting in line?” said a gruff voice.

“Waiting in line,” said Peter.

“Well, then, move forward, why don’t you?”

Peter put his hat on his head and stepped forward smartly, like the soldier, the very good soldier, he had once trained to become.

* * *

In the home of the Count and Countess Quintet, inside the ballroom, as the people filed by her, touching her, pulling at her, leaning against her, spitting, laughing, weeping, praying and singing, the elephant stood broken-hearted.

There were too many things that she did not understand.

Where were her brothers and sisters? Her mother?

Where were the long grass and the bright sun? Where were the hot days and the dark pools of shade and the cool nights?

The world had become too cold and confusing and chaotic to bear.

She stopped reminding herself of her name.

She decided that she would like to die.

T

he Countess Quintet had discovered that it was a somewhat messy affair to have an elephant in one’s ballroom, and so, for matters of delicacy and cleanliness, she engaged the services of a small, extremely unobtrusive man whose job it was to stand behind the elephant, ever at the ready with a bucket and a shovel. The little man’s back was bent and twisted, and because of this, it was almost impossible for him to lift his face and look directly at anyone or anything.

He viewed everything sideways.

His name was Bartok Whynn, and before he came to stand perpetually and forever at the rear of the elephant, he had been a stonecutter who laboured high atop the city’s largest and most magnificent cathedral, working at coaxing gargoyles from stone. Bartok Whynn’s gargoyles were well and truly frightening, each different from the others and each more horrifying than the one that had preceded it.

On a day in late summer, the summer before the winter the elephant arrived in Baltese, Bartok Whynn was engaged in the task of bringing to life the most gruesome gargoyle he had yet conceived, when he lost his footing and fell. Because he was so high atop the cathedral, it took him quite a long time to reach the ground. The stonecutter had time to think.

What he thought was, I am going to die.

This thought was followed by another thought: But I know something. I know something. What is it I know?

It came to him then. Ah, yes, I know what I know. Life is funny. That is what I know.

And falling through the air, he actually laughed aloud. The people on the street below heard him. They exclaimed over it among themselves. “Imagine a man falling to his death and laughing all the while!”

Bartok Whynn hit the ground, and his broken, bleeding and unconscious body was borne by his fellow stonecutters through the streets and home to his wife, who equivocated between sending for the funeral director and sending for the doctor.

She settled, finally, upon the doctor.

“His back is broken and he cannot survive,” the doctor told Bartok Whynn’s wife. “It is not possible for any man to survive such a fall. That he has lived this long is some miracle that we cannot understand and should only be grateful for. Surely it has some meaning beyond our understanding.”

Bartok Whynn, who had, up to this point, been unconscious, made a small sound and took hold of the doctor’s greatcoat and gestured for him to come close.

“Wait a moment,” said the doctor. “Attend, madam. Now he will deliver the words, the important words, the great message that he has been spared in order to speak. You may give those words to me, sir. Give them to me.” And with a flourish, the doctor flung his coat to the side and bent over Bartok’s broken body and offered him his ear.

“Heeeeeeeeeeee,” whispered Bartok Whynn into the doctor’s ear, “heee heee.”

“What does he say?” said the wife.

The doctor stood up. His face was very pale. “Your husband says nothing,” he said.

“Nothing?” said the wife.

Bartok tugged again at the doctor’s coat. Again the doctor bent and offered his ear, but this time with markedly less enthusiasm.

“Heeeeeeeeeeee,” laughed Bartok Whynn into the doctor’s ear, “heeeee heee.”

The doctor stood up. He straightened his coat.

“He said nothing?” said the wife. She wrung her hands.

“Madam,” said the doctor, “he laughs. He has lost his mind. His life is to follow. I tell you he will not – he cannot – live.”

But the stonecutter’s broken back healed in its strange and crooked way, and he lived.

Before the fall Bartok Whynn was a dour man who measured five feet nine inches and who laughed, at most, once a fortnight. After the fall he measured four feet eleven inches and he laughed darkly, knowingly, daily, hourly, at everything and nothing at all. The whole of existence struck him as cause for hilarity.

He went back to work high atop the cathedral. He held the chisel in his hand. He stood before the stone. But he could not stop laughing long enough to coax anything from it. He laughed and laughed, his hands shook, the stone remain untouched, the gargoyles did not appear, and Bartok Whynn was dismissed from his job.

That is how he came, in the end, to stand behind the elephant with a bucket and a shovel. His new position in life did not at all, in any way, diminish his propensity for hilarity. If anything, if possible, he laughed more. He laughed harder.

Bartok Whynn laughed.

And so when Peter, late in the day, in the perpetual, unvarying gloom of the Baltesian winter afternoon, finally stepped through the elephant door and into the brightly lit ballroom of the Countess Quintet, what he heard was laughter.

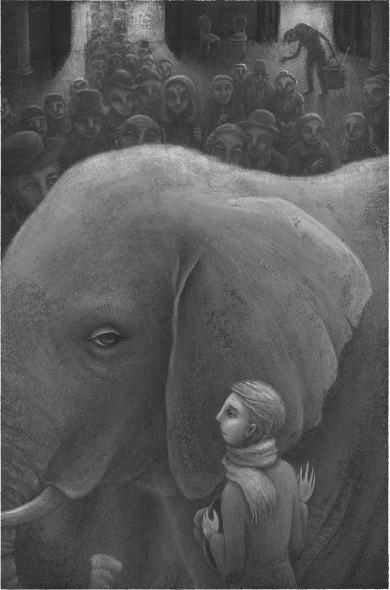

The elephant, at first, was not visible to him.

There were so many people gathered around her that she was obscured entirely. But then, as Peter got closer and closer still, she was finally, and at last, revealed. She was both larger and smaller than he had expected her to be. And the sight of her, her head hung low, her eyes closed, made his heart feel tight in his chest.

“Move along – ha ha hee!” shouted a small man with a shovel. “Wheeeeee! You must move along so that everyone,

everyone

, may view the elephant.”

Peter took his hat from his head. He held it over his heart. He inched close enough to put his hand on the rough, solid flank of the elephant. She was moving, swaying from side to side. The warmth of her astonished him. Peter shoved at the people surrounding him and managed to get his face up next to hers so that he could say what he had come to say, ask what he had come to ask.

“Please,” he said, “you know where my sister is. Can you tell me?”

And then he felt terrible for saying anything at all. She seemed so tired and sad. Was she asleep?

“Move along, move along – ha ha hee!” shouted the little man.

“Please,” whispered Peter to the elephant, “could you … I need you to … could you … would it be possible for you to open your eyes? Could you look at me?”

The elephant stopped swaying. She held very still. And then, after a long moment, she opened her eyes and looked directly at him. She delivered to him a single, great, despairing glance.

And Peter forgot about Adele and his mother and the fortuneteller and the old soldier and his father and battlefields and lies and promises and predictions. He forgot about everything except for the terrible truth of what he saw, what he understood in the elephant’s eyes.

She was heartbroken.

She had to go home.

The elephant had to go home or she would surely die.

As for the elephant, when she opened her eyes and saw the boy, she felt a small shock go through her.

He was looking at her as if he knew her.

He was looking at her as if he understood.

For the first time since she had come through the roof of the opera house, the elephant felt something akin to hope.

“Don’t worry,” Peter whispered to her. “I will make sure that you get home.”

She stared at him.

“I promise,” said Peter.

“Next!” shouted the little man with the shovel. “You must, you simply

must

, move along. Ha ha hee! There are others waiting to see the – ha ha hee! – elephant too.”

Peter stepped away.

He turned. He walked without looking back, out of the ballroom of the Countess Quintet, through the elephant door, and into the dark world.

He had made a promise to the elephant, but what kind of promise was it?

It was the worst kind of promise; it was yet another promise that he could not keep.

How could he, Peter, make sure that an elephant got home? He did not even know where the elephant’s home was. Was it Africa? India? Where were those places, and how could he get an elephant there?

He might just as well have promised the elephant that he would secure for her an enormous set of wings.

It is horrible, what I have done, thought Peter. It is terrible. I should never have promised. Nor should I have asked the fortuneteller my question. I should not have, no. I should have left things as they were. And what the magician did was a terrible thing too. He should never have brought the elephant here. I am glad that he is in prison. They should never, ever let him out. He is a terrible man to do such a thing.