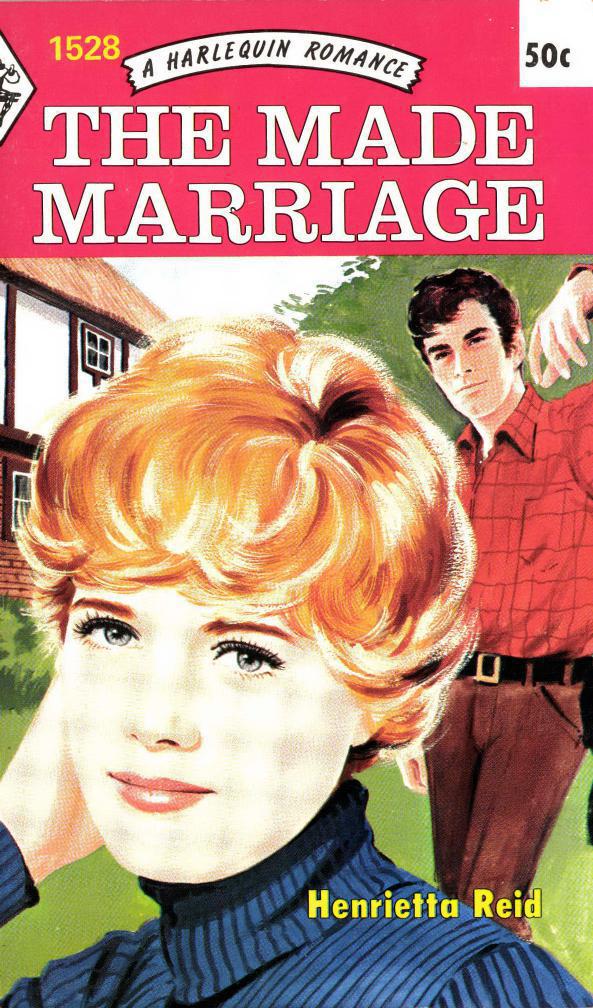

The Made Marriage

Authors: Henrietta Reid

THE MADE MARRIAGE

Henrietta Reid

“

Lonely farmer needs bride

...

Good nature essential and ability to establish warm domestic atmosphere

,”

said the advertisement—and in a fit of bravado Kate answered it, and soon found herself en route for Ireland to become the bride of a man she had never met.

But when she arrived, and met Owen Lawlor, it was only to learn that this was the first he had heard about it

...

CHAPTER

ONE

‘YOU mean you actually bought that piece of junk?’ Margot asked incredulously

.

Kate gazed guiltily at the small teapot lying on the counter, half wrapped in a grubby piece of newspaper.

‘Really, Kate, you are the limit: it has “plated” written all over it, yet you actually coughed up, thinking it was solid silver! How could you have let yourself be taken in?’

‘But the man who brought it looked so old and ill,

’

Kate protested in a small voice, ‘and perhaps he genuinely believed it was old Irish silver,

’

she added feebly. ‘He said it was an heirloom and he had brought it with him from Ireland when his family lost their estates.’

‘Lost his estates, my foot,’ Margot scoffed. ‘He probably comes from a whitewashed cottage with a thatched roof. Will you ever learn not to be so utterly trusting, especially when it comes to so-called antiques? Far from being the genuine article, the pot is only silver plated and I should say not more than a few years old, though, from its condition, I’d say your nice sweet aristocratic old character has given it a rough time.’

‘I am so sorry, Margot,’ Kate mumbled.

And Margot, seeing her cousin’s downcast expression, relented and patted her arm with rough affection. ‘There, don’t take it so much to heart: I expect the Trinket Box will survive. Goodness knows, we’ve weathered worse setbacks, but there’s no doubt about it, things are getting progressively stickier.’

As she spoke Margot gazed about her small domain with a worried frown. Through the bull’s eye glass of the wide bay window, the evening sun cast a golden greenish tinge over its contents: the chased and burnished helmet; the collection of Victorian brooches; the horse brasses; the ruby glass decanters; the hunting prints and miniatures, all the quaint bibelots that formed the stock-in-trade of her little antique shop. It was true it was situated in one of the most fascinating parts of the market town of Sahninster, between the half-timbered town hall and the old coaching inn which was rumoured to have been in olden days a refuge for fugitive highwaymen, but since the town had been bypassed by a motorway, business had fallen off and only occasional visitors to the medieval abbey found their way to The Trinket Box.

Margot shrugged off the feeling of despondency that so frequently gripped her now. How long would it be before she had to confess to her young cousin that the burden of making ends meet was gradually proving too much for even her courageous spirit and that unless by some miracle things improved spectacularly she would seriously have to consider parting with the little business she had inherited from her

gentle

antiquary father.

‘C

ome on, buck up, Kate,’ she said bracingly. ‘There are kippers for tea. I spotted them in the supermarket and remembered how crazy you are about them. We’ll toast ourselves before the fire and gossip.’

Kate smiled wanly and pushed back from her small round face the thick locks that held, in certain lights, the warm rich tints of heather honey. Cousin Margot was once again making the best of her foolish blunders, she knew. She was acutely conscious that it was not the first time she had allowed her soft heart to rule her head with disastrous

consequences to the finances of The Trinket Box. During the previous week, for instance, young Susan Edmundson had set her heart on a dainty silver comfit box displayed in the front of the window. Tears had glittered in her pale rather sly eyes when Kate had gently pointed out that, although diminutive, the box was old and indeed quite valuable.

‘But this is all I have!’ Susan had dejectedly deposited a pile of sticky coins on the counter. ‘Mum’s ill in hospital and it’s her birthday tomorrow and it will be just the thing to hold her hairpins: you see, she wears her hair in a bun,’

she

had added hopefully.

Kate had nodded. She had often seen Mrs. Edmundson behind the plate glass of her small, though prosperous, millinery shop. A widow, it was well-known that Mrs. Edmundson hopelessly spoiled Susan and indulged her every whim. It was pleasant to see the child’s anxiety to give her mother happiness and Kate had hesitated before returning the trinket to the window.

Susan had sniffed dismally. ‘I know she’d just love it, and I could pay you the rest when I get my pocket-money. Mum always gives me plenty.’

‘When do you get your pocket-money?’ Kate had asked with the last remnants of her fast departing caution.

‘At the end of the week,’ Susan had answered promptly, ‘and I’ll come along with it right away, I promise!’

Kate had paused: then, as the large blue eyes gazed at her appealingly, said, ‘Very well then, if you promise on your honour to bring along the balance at the end of the week I’ll let you have it.’

‘Perhaps you’ll put it in a box for me,’ Susan had asked promptly, now that the battle was won, and Kate had reached behind the counter for a small cardboard box and carefully packed the trinket in violet tissue-paper.

Susan had watched these proceedings with absorbed interest then, clutching her gift, had departed glowing.

But as the week drew to a close Kate had realised, with dismay, that Susan had no intention of paying the balance.

And now, once more, by her foolish good nature, she had placed her cousin in difficulties!

Margot, with a resigned sigh, collected the letters that had arrived by the afternoon post and had been placed on the counter in a pile by Kate. ‘Um, most of them look suspiciously like bills,’ Margot remarked as she scanned the outsides. ‘However, we’ll go into them by the sitting-room fire.’ She pushed the bundle into the pocket of her smock and when she had carefully locked and barred the shop door led the way into the tiny room behind the shop.

In spite of the fact that it was spring the evening was chilly and Kate’s despondency lifted as soon as they were seated on either side of the roaring fire. She had always loved this tiny room with its old winged armchairs and time-scarred furniture. It was the sort of room upon which firelight played rosily and it had not changed very much since she had first been taken under her cousin Margot’s wing after her parents’ tragic death in a boating accident.

It was seldom she allowed herself to remember those desperate moments in the icy water after the dinghy had capsized, or the expression on her father’s face, whom she had always known as gay and light-hearted, when, having towed her to the beach, he had returned for a despairing search for his young wife. Neither had been seen again. The little galleon-like room had been a refuge then, encircling her in its warmth and air of serene permanence, and now as she took the

bubbling kettle off the hob and filled the teapot she exulted in its lack of change. Nothing was different, except, of course, Bedsocks who sat purring on the rag rug in front of the fire.

Margot gazed at the little cat suspiciously as it waved a languid white-tipped paw and crinkling its black velveteen nose thoroughly washed the left-hand side of its face. ‘Bedsocks looks remarkably smug,’ she observed. ‘I wonder if she’s been at the kippers again.’

Kate glanced hastily at the small round table, laid for supper, and to her relief saw that the kippers were intact. ‘I think Bedsocks has turned over a new leaf,’ she remarked a little reproachfully. ‘It’s been ages since she’s stolen anything or climbed on the table.’

‘That animal is incapable of reformation,’ Margot replied unsympathetically. ‘She’s simply getting cleverer at hiding her tracks.’

Bedsocks stretched her dainty pink tongue to its fullest extent and curling the tip yawned elaborately, then gazed unwinkingly with pale topaz-coloured eyes at her detractor until Margot, in spite of herself, gave an unwilling smile. ‘It’s hard to remember what a wretched little bundle of fur she was when you brought her home.’

Kate nodded. It had been a cold stormy night in autumn when she had seen this small huddled object crouched between the sooty railings of the park, vainly trying to find protection amongst the withered leaves and bare branches of the bordering shrubs. It had offered no resistance when she had lifted it up and tucked it under her coat and later in front of the sitting-room fire when its fur had dried out had expanded miraculously into a ball of black fluff with symmetrical white socks and vest.

As soon as the evening meal was over and the table cleared, Margot began to deal with the mail. ‘Kenneth’s calling along tonight and threatens to pop the same old question,’ she said as she took up the first letter.

Kate smiled. Kenneth Millbanke was not a particular favourite of hers: an accountant in a big manufacturing firm in the adjoining town, since his mother’s death he had lived by himself in a big red villa and was inclined to self-importance. He assumed a censorious and slightly patronising attitude towards Margot’s young cousin, yet his tenacity in pursuing Margot appealed to all the romance in Kate’s nature. ‘In that case I’ll do some repairs to my clothes in the privacy of my chamber,’ Kate said mischievously.

‘And high time too,’ Margot snorted, before returning to her correspondence.

‘

You’re incredibly careless as a rule.’ Gradually her face assumed the worried frown she was inclined to wear when dealing with business matters, so that it was not until she gave an exclamation of dismay that Kate, who was seated on the rug teasing Bedsocks with a discarded envelope, looked up and saw to her alarm that Margot was staring incredulously at a long legal-looking sheet of paper, her face pale and shocked.

Kate jumped to her feet. ‘What is it, Margot?’

Her cousin stared at her unseeingly, then said hoarsely, ‘It’s a letter from the solicitors of the company who own The Four-in-Hand. It seems they want to extend their premises and have decided to take over The Trinket Box.’

Kate grew almost as white as her cousin. ‘But they can’t!’ she exclaimed at last. ‘They can’t just calmly take it away from you after all these years.

’

‘But they can,’ Margot replied wryly. ‘It’s theirs, after all. My father was only a tenant and, although he had an understanding with the company, matters were never put on a proper businesslike basis. Of course there’s the usual regrets and references to the long and pleasant association, etcetera, but it means the end of the road as far as we’re concerned.’

To Kate’s alarm, she saw tears start to Margot’s eyes. She had never known her cousin to show defeat or weakness no matter how heavy the odds were against her: it was Margot who had rallied and reassured her and on whose strength she had relied during the early days of her loss.

‘Perhaps if you wrote to them and explained how you’d hate to give up The Trinket Box they’d understand and change their minds,’ she suggested hopefully. But she felt overwhelmed by the odds against them. To her the owners of The Four-in-Hand were vague and powerful men who sat around enormous austere tables and made pontifical and irreversible decisions concerning their various properties.

Margot shook her head and smiled wryly at her cousin’s

naiveté

. ‘I’m afraid big companies don’t indulge in sentimental considerations. The Four-in-Hand is only one of their interests

:

they own hotels and roadhouses all over the country. No, I’m afraid we’ve had it as far as The Trinket Box is concerned.’ Very carefully she replaced the fateful letter in its envelope. Her actions were slow and precise, and Kate, who could at times be surprisingly perceptive, realised that Margot was deliberately giving herself time to regain her self-possession. ‘Anyway, sooner or later, we’d have had to close up: this has simply precipitated things. I’m afraid, Kate, that The Trinket Box simply wasn’t paying its way.’

‘

Not paying its way?’ Kate echoed in bewilderment. ‘But I sold lots of things last week.’