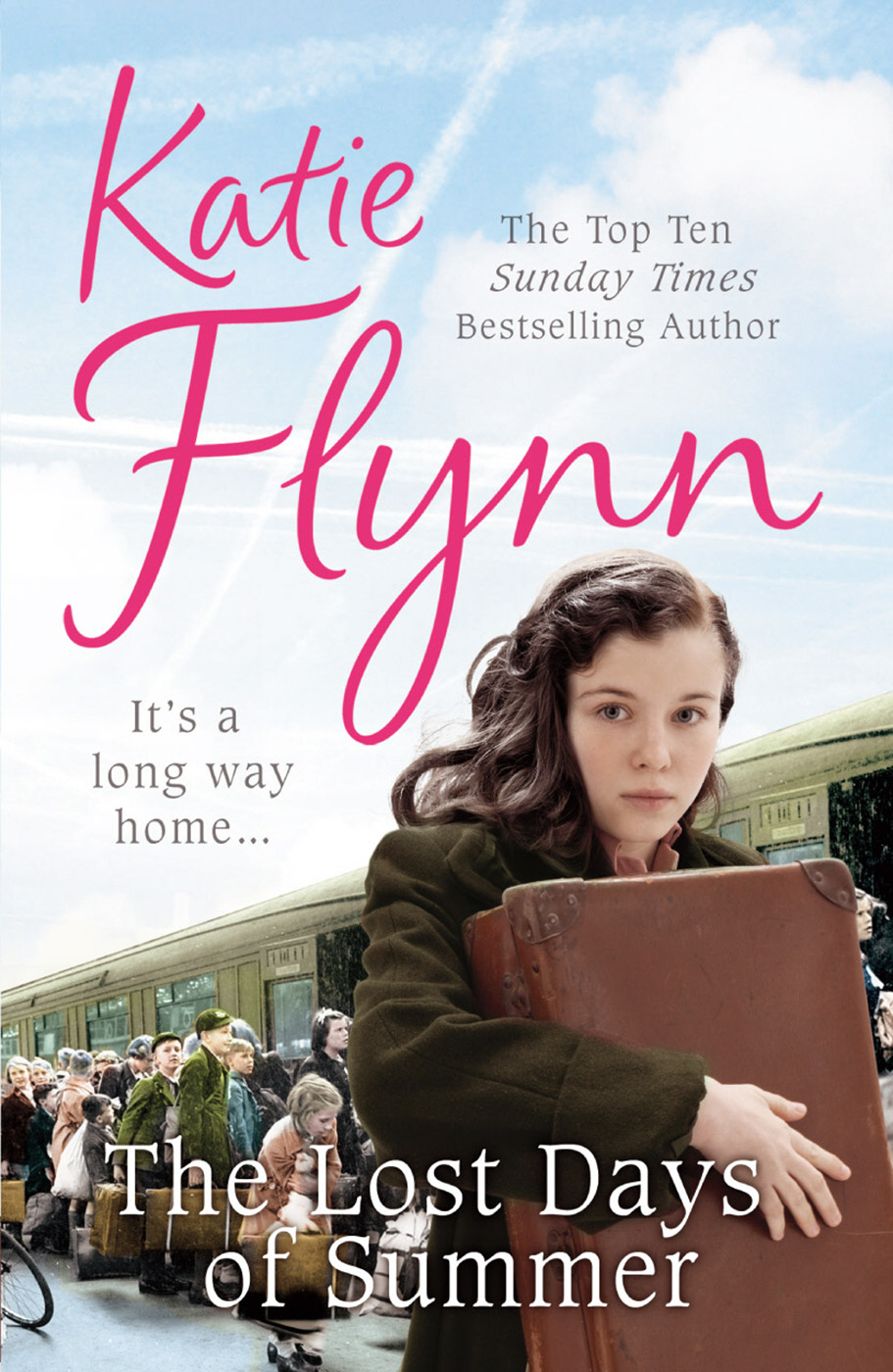

The Lost Days of Summer

Read The Lost Days of Summer Online

Authors: Katie Flynn

About the Book

Nell Whitaker is fifteen when war breaks out and, despite her protests, her mother sends her to live with her Auntie Kath on a remote farm in Anglesey. Life on the farm is hard, and Nell is lonely after living in the busy heart of Liverpool all her life. Only her friendship with young farm hand Bryn makes life bearable. But when he leaves to join the merchant navy, Nell is alone again, with only the promise of his return to keep her spirits up.

But Bryn's ship is sunk, and Bryn is reported drowned, leaving Nell heartbroken. Determined to bury her grief in hard work, Nell finds herself growing closer to Auntie Kath, whose harsh attitude hides a kind heart. Despite their new closeness, however, she dare not question her aunt about the mysterious photograph of a young soldier she discovers in the attic.

As time passes, the women learn to help each other through the rigours of war. And when Nell meets Bryn's friend Hywel, she begins to believe that she, too, may find love . . .

About the Author

Katie Flynn has lived for many years in the northwest. A compulsive writer, she started with short stories and articles and many of her early stories were broadcast on Radio Merseyside. She decided to write her Liverpool series after hearing the reminiscences of family members about life in the city in the early years of the twentieth century. She also writes as Judith Saxton. For many years she has had to cope with ME, but has continued to write.

Also by Katie Flynn

A Liverpool Lass

The Girl from Penny Lane

Liverpool Taffy

The Mersey Girls

Strawberry Fields

Rainbow’s End

Rose of Tralee

No Silver Spoon

Polly’s Angel

The Girl from Seaforth Sands

The Liverpool Rose

Poor Little Rich Girl

The Bad Penny

Down Daisy Street

A Kiss and a Promise

Two Penn’orth of Sky

A Long and Lonely Road

The Cuckoo Child

Darkest Before Dawn

Orphans of the Storm

Little Girl Lost

Beyond the Blue Hills

Forgotten Dreams

Sunshine and Shadows

Such Sweet Sorrow

A Mother’s Hope

In Time for Christmas

Heading Home

A Mistletoe Kiss

For Heather Chorlton of Holyhead who first

drew my attention to the Swtan cottage;

thank you, Heather!

Firstly, I’d like to thank Eric Anthony of the Holyhead Maritime Museum for allowing Brian to photograph his grandfather’s ‘death penny’, thus opening up a whole new chapter of my book. He also guided us through the museum – which is wonderful – and directed me to books and First World War photographs and memorabilia, especially

Master Mariner

, the biography of the late Captain William Henry Hughes, DSC, written by Dewi Francis; an exellent and amusing work dealing with both world wars.

I also spent a good deal of time at the Swtan cottage, which has been beautifully restored by local volunteers and proved irresistible as a setting for my story so my thanks to them.

Last but not least my sincere thanks go to Nancy Webber, who untangled tangles, righted wrongs and generally kept me on the straight and narrow.

September 1939

Nell Whitaker sat scrunched up in the corner seat of the train which was taking her where she had no desire to go, and looked at her reflection in the dirt-smeared window pane. The compartment was full, and she hoped the other passengers thought that she was watching the passing scene and did not realise that she was balefully examining her own face.

In the window glass she saw a thin fifteen-year-old with a tumbled mass of dark hair, large dark eyes and, she had to admit, a mouth which drooped with bitterness and disappointment. And no wonder! Her mam had promised – absolutely promised – that she should not be sent away, evacuated as they called it. Yet here she was, on a train, heading for heaven knew where.

When war had been declared three weeks previously, her younger cousins had been sent with the rest of their schoolmates to a small village on the Wirral, where they had felt out of place and unwanted. There had been no question of evacuation so far as Nell herself was concerned; she had started at secretarial college within days of war being declared and her mother had promised that the two of them would continue to live their lives as they had in peacetime. ‘If you do well at college I might be able to get you a job with me,’ she had said. ‘They know I’m hardworking and reliable, and they’ll guess that you’re the same. But even if not, secretarial jobs should be easier to find now that so many employees have either volunteered for the services or been called up.’ She had sighed wistfully. ‘I’d love to join the WAAF and do my bit for the war effort, but that’s impossible whilst you’re still in college. If only you’d taken a job in a factory – factory workers get awfully well paid . . . but that’s not what you wanted, and I’m the last person to push you into a job you’d dislike. So if you work very hard and gain the qualifications you’ve talked about, I suppose I must put up with it.’

Nell had promised to do her best, secretly surprised that her flighty, fun-loving mother had even considered joining up and wearing a uniform, but she had worked hard and passed the weekly tests with flying colours. And Mum had been pleased and proud, Nell thought miserably now, staring out at the countryside trundling past. There had been no question of sending her away then.

Meanwhile, the cousins had stayed where they were, though Matty, the closest to Nell in age, had told her before they left that they didn’t want to go, had no desire to leave Liverpool, no matter what. ‘They say there’ll be bombin’, or paratroopers dressed as nuns descendin’ from the skies,’ she had pointed out. ‘I reckon it’s all talk, meself, and we’ll be as safe here as anywhere.’

‘But won’t you like living in the country?’ Nell had asked. ‘I’ve always imagined life on a farm must be great fun.’

Matty had snorted. ‘Fun?’ she had said witheringly. ‘It’s bleedin’ hard work, from wharr I’ve heared tell, an’ no shops nor cinemas for miles. An’ country schools is horrible, wi’ outside privies and mud everywhere. Give me good old Bootle any day.’

Now, Nell looked round the crowded, stuffy compartment; it was a cold and windy day and no one wanted to open the window. The train which was to take her right across Wales and on to an island she had never even heard of seemed to be constantly held up, which meant that the journey, which someone had told her normally took two or three hours, might easily last all day.

Nell sighed and returned to the contemplation of her miserable reflection. She told herself that she and her mother loved each other dearly and had been very close – as close as sisters, her mother always claimed somewhat coyly – since her father, Tom Whitaker, had died. And now she felt that her mother had turned against her, reneging on her promise. She said she was sending Nell away because her sister, Nell’s aunt Kath, had written suggesting that Trixie might send her eldest daughter to Ty Hen, her farm on Anglesey, where she would be safe, well looked after and a great help.

Nell had looked at her mother, almost unable to believe her ears. ‘I didn’t even know I had an aunt Kath, and I don’t want to leave Liverpool,’ she had said. ‘Besides, you’re staying here, so why shouldn’t I? If it’s safe for you, it’s safe for me.’

She had watched her mother’s face flush and seen her eyes sparkle without understanding the cause, but presently she had learned the reason for her mother’s excitement and also, in a way, for her own banishment. ‘I’m going to join the WAAF, queen, along with your Auntie Lou,’ her mother had said. ‘They won’t accept anyone with a dependent child, so when your Auntie Kath wrote offering to have you I was delighted.’ She must have seen her daughter’s horrified expression, for she had added hastily: ‘Oh, queen, don’t look like that! Don’t you see? You’d be doing your bit for our country too, because growing food is much more important than being someone’s secretary.’

‘But Mam, I’m doing so well,’ Nell had wailed. ‘Is there a secretarial college near this woman’s farm? Might I go to it to finish my course?’

Her mother had looked uneasy. ‘It might be possible,’ she had said. ‘If you could continue your training, you’d be killing two birds with one stone. You’d be helping your aunt whilst planning for your own future. As soon as you arrive at the farm you can make enquiries; there’s no harm in that.’

‘Right. And now you can jolly well tell me why I’ve never heard of this Auntie Kath before,’ Nell had said firmly. ‘I know you’ve got a lot of relatives, and some of them I’ve never met, but I’ve never even heard of a Kath!’

Trixie Whitaker had looked rather guilty. ‘Oh, Kath and I fell out. She was set to marry a feller I – I didn’t approve of. There was a big age gap . . . in fact the whole family disapproved, so when Kath wouldn’t take no notice, but married and went off to Anglesey, we lost touch. You could have knocked me down with a feather when I got her letter. She said that Owain – that’s the name of the feller she married – had died, and she was finding the farm too much for herself and the one worker left to her. I wrote back explaining I’d been widowed myself and saying I’d be glad to entrust my eldest girl to her care.’ She had chuckled, seeing her daughter’s puzzled expression. ‘Kath didn’t even know your name, lerralone that you were an only child. Still an’ all, it were a generous offer and I’m sure you and Kath will take to one another. She’s not a bad old stick; in fact she and I were close until the quarrel. Why, I reckon she’ll even pay you, ’cos she’d have to pay a land girl, only it seems she prefers family.’

‘If she pays me, then even if there was a secretarial college two minutes’ walk away I wouldn’t be able to attend it,’ Nell had said gloomily. ‘And why didn’t you tell me when my aunt’s letter arrived? You did promise you’d never send me away, you know, or have you forgotten?’

‘War changes things,’ her mother had said vaguely. ‘Just be grateful that I’m sending you somewhere safe, and to a blood relation.’

‘What if I hate it?’ Nell had asked suspiciously. ‘Suppose Auntie Kath hates me, for that matter? Would one of the other aunts take me in?’ She had pulled a face at the thought, for fond though she was of her mother’s many sisters and cousins, their small houses were already horribly overcrowded. She got on well with Auntie Lou, but she was going away with her mother and Nell had no particular desire to live with any of the others.

Trixie, however, had shaken her head decisively. ‘I’d never forgive myself if you came back to Liverpool and got injured, or even killed, when the Germans start their bombing offensive,’ she had said, and for the first time Nell had thought her mother sounded serious. ‘If you are truly unhappy, then you must write and tell me and I’ll try to find you another billet, but not in a big city. Promise me you’ll stay with your aunt for at least six months. And remember the old saying: Out of the frying pan, into the fire. There are many worse places than a farm in the heart of the country, so please, queen, make the best of it. If I hate the WAAF, there’s no way out for me until the war’s over; why should it be different for you?’

After that, events had moved so fast that Nell and her mother had been too busy to discuss the matter further. Trixie’s papers had arrived, telling her to report to Bridgnorth in Shropshire the following Monday, and detailing the personal possessions she was allowed to take with her. Auntie Lou’s daughters were already employed by the munitions factory in Long Lane, Aintree, and had taken digs to be near their work, so Lou and Trixie sold the contents of their houses and left it to the landlord to find new tenants, thus making it impossible for Nell to run home, even if she wished to do so.