The Long Descent (13 page)

Too many of these people, however, didn't take the time to work out just how much their new McMansion would cost to own, maintain, and repair, and soaring real estate prices made it very difficult to remember that every boom sooner or later ends in a bust. Once these realities began to sink in, many people who expected to get rich off their houses found themselves in an awkward predicament as their monthly paychecks no longer covered their monthly expenses. Home equity loans offered one popular way to cover the gap, but once housing prices began to slump and banks cut back on easy credit, that option shut down. From that point on the possibilities narrowed sharply, and every option â taking on more debt, deferring repairs and maintenance, leaving bills unpaid â eventually adds to the total due each month. Sooner or later, the rising tide of expenses overwhelms available income, and the result is foreclosure.

That's catabolic collapse in a nutshell. Like suburban mansions, civilizations are complex, expensive, fragile things. To keep one going, you have to maintain and replace a whole series of capital stocks: physical (such as buildings); human (such as trained workers); informational (such as agricultural knowledge); social (such as market systems); and more. If you can do this within the “monthly budget” of resources provided by the natural world and the efforts of your labor force, your civilization can last a very long time. Over time, though, civilizations tend to build their capital stocks up to levels that can't be maintained; each king (or industrial magnate) wants to build a bigger palace (or skyscraper) than the one before him, and so on. That puts a civilization into the same bind as the homeowner with the oversized house. In the terms used in the original paper, production falls short of the level needed to maintain capital stocks, and those stocks are converted to waste: buildings become ruins, populations decrease, knowledge is lost, social networks disintegrate, and so on.

What happens then depends on whether the civilization's most important resources are being used at a sustainable rate or not. Resources used at a sustainable rate are like a monthly paycheck; in the long run, you've got to live within it, but as long as you can keep expenses on average at or below your paycheck, you know you can get by. If a civilization gets most of its raw materials from ecologically sound agriculture, for example, the annual harvest puts a floor under the collapse process. Even if things fall apart completely â if the homeowner goes bankrupt and has her house foreclosed on, to continue the metaphor â that monthly paycheck will allow her to rent a smaller house or an apartment and start picking up the pieces. Civilizations such as imperial China, which were based on sustainable resources, cycled through this process many times, from expansion through overshoot to a self-limiting collapse that bottomed out when capital stocks got low enough to be supported by the stable resource base.

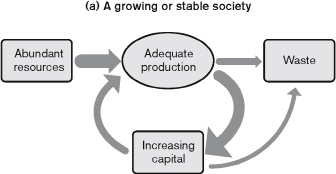

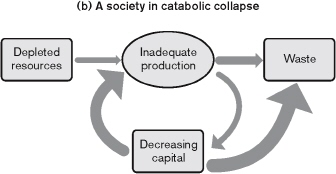

Diagram 3.1. How Catabolic Collapse Works

In a growing or stable society, the resource base is abundant enough that production can stay ahead of the maintenance costs of society's capital â that is, the physical structures, trained people, information, and organizational systems that constitute the society. Capital used up in production or turned into waste can easily be replaced.

In a society in catabolic collapse, resources have become so depleted that not enough is available for production to meet the maintenance costs of capital. As production falters, more and more of society's capital becomes waste, or is turned into raw material for production via salvage. If resource depletion can be stopped, the loss of capital brings maintenance costs back down below what production can meet, and the catabolic process ends; if resource depletion continues, the catabolic process continues until all capital becomes waste.

If the civilization depends on using resources at an unsustainable rate, though, the situation becomes much more serious. In terms of the metaphor, our homeowner bought the house with lottery winnings, not a monthly paycheck; his income is only a fraction of the amount he spends each month. In the first flush of prosperity, it's all too easy for our lottery winner to commit to far bigger monthly expenses than his income can cover. By the time the problem becomes clear, very little can be done about it. The money is gone, our homeowner is faced with bills his monthly income won't even begin to cover, and by the time the collection agencies get through with him he may very well end up living on the street. Civilizations such as the Maya, which used vital resources at an unsustainable rate, went through this process; the “collection agencies” of nature left nothing behind but crumbling ruins in the Yucatan jungle.

This is not good news for our modern industrial civilization because its capital stocks are supported by winnings from the geological lottery that laid down fantastic amounts of fossilized solar energy in the form of coal, oil, and natural gas. Even the very small fraction of our resource base that comes from the “paycheck” of agriculture, forestry, and fishing depends on fossil fuels. Since the late 1950s, scientists have been warning that what's left of our fossil fuel resources won't sustain our current industrial system indefinitely, much less support the Utopia of perpetual economic growth we have grown up expecting. For the most part, these warnings have been roundly ignored. If they continue to be ignored until actual shortages begin, we may be in for a very ugly future.

That future may be closer than most people like to think. The collapse of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina drew attention from around the world, but few people seem to have noticed the implications of the Big Easy's fate. The United States suffers catastrophic hurricanes every decade or so. In the past, the destruction was followed by massive rebuilding programs â but not this time. The French Quarter and a few other mostly undamaged portions of the city have reestablished a rough equivalent of their former lives, but much of the rest of the city has been bulldozed or simply abandoned to the elements. The ruins of the Ninth Ward, like the hundreds of abandoned farm towns that dot the Great Plains states and the gutted cities of America's Rust belt, may be a harbinger of changes most Americans will find it acutely uncomfortable to face.

The housing metaphor breaks down in two places, though. First, even in societies dependent on unsustainable resource use, catabolic collapse unfolds gradually, in a distinctive rhythm of crisis followed by partial recovery. It's similar to a homeowner who, facing financial ruin, sells his existing house and uses the proceeds to buy a smaller one; when he can no longer afford that, he repeats the process, until eventually he either moves into a home he can afford, or he ends up in a cardboard box on the street. In terms of the model, the mismatch between production and the maintenance costs of capital causes a certain fraction of a civilization's capital stock to be turned to waste. Since that fraction no longer has to be maintained, and because some of it can be recycled into raw materials, each wave of collapse is followed by a respite, as costs drop far enough to give the declining civilization breathing room. The result is the stairstep pattern of decline found in the histories of nearly every dead civilization.

Second, a civilization has a fractal structure â that is, the same patterns that define it at the topmost level also appear on smaller scales. The cities of eastern China that were mentioned at the beginning of this chapter maintained urban life through the fall of empires precisely because of this fractal structure; a single city and its agricultural hinterland can survive even if the larger system comes apart. The recent spread of peak oil resolutions and projects by cities and towns across America is thus a very hopeful sign. It's going to take drastic changes and a great deal of economic rebuilding before these communities can get by on the more limited resources of a deindustrial future, but the crucial first steps toward sustainability are at least on the table now. If our future is to be anything but a desperate attempt to keep our balance as we skid down the slope of collapse and decline, these projects may well point the way.

Four Facets of Catabolic Collapse

How will the process of catabolic collapse work itself out in the present situation? Prophecy is among the chanciest of arts, but a careful eye on current trends allows some educated guesses to be made about the way the near future is likely to unfold. Though the future we face is far from apocalyptic, four horsemen still define the most likely scenario.

First out of the starting gate is

declining energy availability.

Around 2010, according to the best current estimates, world petroleum production will peak, falter, and begin an uneven but irreversible descent. North American natural gas supplies are predicted to start their terminal decline around the same time. Some of the slack can be taken up by coal, wind and other renewables, nuclear power, and conservation â but not all. As oil depletion accelerates, and other resources such as uranium and Eurasian natural gas hit their own production peaks, the shortfall widens, and many lifestyles and business models that depend on cheap energy become nonviable.

The second horseman, hard on the hooves of the first, is

economic

contraction.

Energy prices are already beginning to skyrocket as nations, regions, and individuals engage in bidding wars driven to extremes by rampant speculation. The global economy, which made economic sense only in the context of the politically driven low oil prices of the 1990s, will proceed to come apart at the seams, driving many import- and export-based industries onto the ropes, and setting off a wave of bankruptcies and business failures. Shortages of many consumer products will follow, including even such essentials as food and clothing. Soaring energy prices will have the same effect more directly in many areas of the domestic economy. Unemployment will likely climb to Great Depression levels, and poverty will become widespread even in what are now wealthy nations.

The third horseman, following the second by a length or two, is

collapsing public health.

As poverty rates spiral upward, shortages and energy costs impact the food supply chain; energy- intensiveâhealth care becomes unaffordable for all but the obscenely rich; global warming and ecosystem disruption drive the spread of tropical and emerging diseases; malnutrition and disease become major burdens. People begin to die of what were once minor, treatable conditions. Chronic illnesses such as diabetes become death sentences as the cost of health care climbs out of reach for most people. Death rates soar as rates of live birth slump, launching the first wave of population contraction.

The fourth horseman, galloping along in the wake of the first three, is

political turmoil.

What political scientists call “liberal democracy” is really a system in which competing factions of the political class buy the loyalty of sectors of the electorate by handing out economic largesse. That system depends on abundant fossil fuels and the industrial economy they make possible. Many of today's political institutions will not survive the end of cheap energy, and the changeover to new political arrangements will likely involve violence. International affairs face similar realignments as nations whose power and influence depend on access to abundant, cheap energy fall from their present positions of strength. Today's supposedly “backward” nations may well find that their less energy- dependent economies turn into a source of strength rather than weakness in world affairs. If history is any guide, these power shifts will work themselves out on the battlefield.

The most important thing to remember about all four of these factors is that they're self-limiting in the near term. As energy prices soar, economies contract, and the demand for energy decreases, bringing prices back down. Even as the global economy comes apart, human needs remain, so local economies take up the slack as best they can with the resources on hand, producing new opportunities and breathing new life into moribund sectors of the economy. As public health fails, populations decline, taking pressure off other sectors of the economy. As existing political arrangements collapse, new regimes take their place, and, like all new regimes, these can be counted on to put stability at the top of their agendas.