The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (34 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

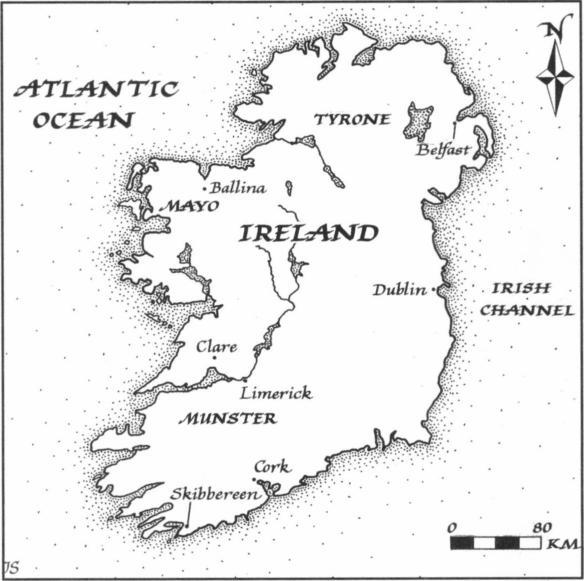

Locations in Ireland mentioned in Chapter I I

No one knows exactly when the potato came to Ireland, but it appears

to have been during the last fifteen years of the sixteenth century' Irish

farmers soon noticed that the strange tuber thrived in their wet and often

sunless climate. Potatoes produced their greatest yields in years when oats

were decimated by the rain from repeated Atlantic depressions. Planted in well-drained, raised fields, potatoes were highly productive and reliable,

even on poor soils. Ireland's long growing season without temperature extremes was ideal for the early European potato, which sprouted growth

and flowers during long summer days and tubers in frost-free autumns,

conditions very similar to those in many parts of the Andes. Unlike cereals, the tubers were remarkably immune to sudden climatic shifts. This

was true almost anywhere in northern Europe, but in Ireland the wet climate especially favored the potato. While other crops rotted above

ground, potatoes quietly grew below the surface. Easy to cook and store,

they seemed an ideal food for the Irish poor. Above all, they were an effective famine food. The potato-cereal combination offered a safeguard

against the failure of either crop. As long as a balance was maintained between the two, the Irish had a reasonably reliable safety net against hunger.

At first the potato was merely a supplement to the Irish diet, except

throughout Munster in the south, where the poorest country people embraced it as a staple very early on. Wrote an observer in 1684: "Ye great

support of ye Poore sortes of people is thire potatoes." They were a winter

food, consumed between "the first of August in the autumn until the

feast of Patrick in the spring." 2 The harvest was so casual that many farmers simply left the tubers in the ground and dug them out when required.

They learned the hard way that a hard frost would destroy the crop in

short order.

Potato cultivation increased twentyfold over the next half century, despite a terrible famine in the exceptional cold of 1740 and 1741, when

both the grain and potato crops failed; 1740-1 became known as Blaidhain an air, "the year of the slaughter." An unusually long spell of cold

weather destroyed both grain and potato crops and killed livestock, even

seabirds. By this time, the poor of the south and west were depending almost entirely on potatoes and were especially vulnerable to crop failure.

The government intervened aggressively, prohibiting grain exports and deploying the army to provide famine relief. There was little excess food in

Europe, partly because of poor harvest and also because of the War of Austrian Succession. Instead, "large supplies of provisions arrived from America."3 Both local landlords and gentry, and members of the Anglican

church organized large scale charity relief in the form of free food, subsidised grain, and free meals. This generosity was sparked more by fear of social disorder and epidemic disease than by altruism. Despite the assistance, large numbers of the poor took to the roads to beg for relief or to

move to the towns in search of food, employment, or a departing ship. Between 300,000 and 400,000 people perished of dysentery, hunger, and typhus in a famine that foreshadowed the great tragedy of the 1840s. In the

end, at least 10 percent of Ireland's population perished of starvation and

related medical ills. The famine demonstrated that neither potatoes nor

oats were a complete panacea to Ireland's farming problems, partly because

stored potatoes only kept about eight months in the damp climate.

As memories of the famine faded, the explosion in potato farming continued. The late eighteenth century was the golden age of the Irish

potato, "universally palatable from the palace to the pig-sty."4 Potatoes

formed a substantial part of the diet of the wealthy and the entire diet of

the poor. The excellent Irish strains developed during these years were admired and planted throughout northern Europe not only for human use

but as animal fodder. By the 1790s, farmers were throwing out large

numbers of surplus potatoes each year, even after feeding their cattle and

pigs. "They left them stacked in heaps at the back of ditches, piled them

in the gaps of fences, used them as top dressing, buried them, or stacked

them in fields and burned them."5

Visitor after visitor remarked on the healthy looks of Irish countryfolk,

and their cheerful demeanor, and their constant dancing, singing, and

storytelling. By the end of the eighteenth century, physicians were recommending potatoes "as a supper to those ladies whom providence had not

blessed with children, and an heir has often been the consequence."6 John

Henry wrote in 1771 that where "the potato is most generally used as

food, the admirable complexions of the wenches are so remarkably delicate as to excite in their superiors very friendly and flattering sensations." 7

In 1780, traveler Philip Lucksome observed that the poorer Irish lived on

potatoes and milk year round "without tasting either bread or meat, except perhaps at Christmas once or twice."8

Everyone grew potatoes in rectangular plots separated from their neighbors' by narrow trenches. Each tract was about two to three meters wide,

fertilized with animal dung, powdered shell, or with seaweed in coastal areas. Using spades called toys, ten men could turn over and sow 0.5 hectare with potatoes in a day. To sow a cereal crop of the same area in the same

time would take forty. The Irish "raised fields," sometimes called "lazy

beds," could produce as many as seventeen tons of potatoes a hectare, an astounding yield when compared with oats. The potato had obvious advantages for land-poor farmers living in complete poverty. With the vitamins

from their tubers and milk or butter from a few head of cattle, even the

poorest Irish family had an adequate, if spartan, diet in good harvest years.

Oblivious of the potential dangers from weather and other hazards,

Ireland moved dangerously close to monoculture. Grain was no longer

part of the diet in the south and west of the country and had become predominantly a cash crop in the north. The beauty of the potato was that it

fed the laborers who produced oats and wheat for export to bread-hungry

England. The illusion of infallible supply caused a growing demand for

Irish potatoes in northeast England to feed the growing populations of

rapidly industrializing Liverpool and Manchester.

In 1811, at the height of the Napoleonic Wars, a writer in the Munster

Farmers' Magazine called potatoes "the luxury of the rich and the food of

the poor; the chief cause of our population and our greatest security

against famine."9 But for all their advantages, potatoes were not a miracle

crop. Unusually wet or dry summers and occasional exceptionally cold

winters subjected the country to regular famine. The combination of rain

and frost sometimes killed both cereals and potatoes. Even in plentiful

years, thousands of the poor were chronically unemployed and dependent

on aggressive government intervention for relief. Many Irish workers, including many skilled linen workers, emigrated to distant lands to escape

hunger. In 1770 alone, 30,000 emigrants left four Ulster ports for North

America. They departed in the face of rapid population growth, archaic

land tenure rules that subdivided small farming plots again and againand the ever-present specter of famine.

The periodic food shortages that plagued Ireland between 1753 and 1801

were mostly of local impact, with relatively low mortality. 10 A serious food shortage developed in 1782/83, when cold, wet weather destroyed much

of the grain crop at the height of a major economic slump. Private relief efforts and aggressive intervention by the Irish government averted widespread hunger. The Earl of Carlisle, at the time the lord lieutenant of Ireland, disregarded the lobbying of grain interests, embargoed food exports

to England and made £100,000 available as bounty payments on oat and

wheat imports. Food prices fell almost immediately. When the severe winter of 1783/84 prolonged the food crisis, the lord lieutenant once again intervened. He assumed control over food exports and made money available for relief at the parish level in affected areas. Within ten days, the

parish scheme brought generous rations for the needy: a pound of bread, a

herring and a pint of beer daily. The number of deaths was much lower

than it had been during the disaster of 1740-42. Government's priorities

were clear and humane, and were matched by rapid response to needs.

An Act of Union joined England and Ireland in 1800. Ireland lost her

political and legislative autonomy and her economic independence. The

decades after 1800 saw Britain embark on a course of rapid industrialization that largely bypassed Ireland, where competition with their neighbor's highly advanced economy, the most sophisticated in Europe, undermined many nascent industries. By 1841, 40 percent of Britain's male

labor force was employed in the industrial sector, compared with only 17

percent of Irishmen. Much of the deindustrialization in the famed Irish

linen industry came from the adoption of labor-saving devices. New

weaving machinery and steam power had transformed what had been a

cottage industry into one concentrated in large mill facilities centered

around Belfast in the north. Until the factories came along, thousands of

small holders had subsisted off small plots of land and weaving and spinning. Now, having lost an important source of income, they were forced

to depend on their tiny land holdings, and above all on the potato. And

in lean years, the authorities in London were less inclined to be sympathetic than their Irish predecessors.

Irish commercial agriculture, which generated enough cattle and grain

exports to feed 2 million people, required that as much as a quarter of Ireland's cereals and most livestock be raised for sale abroad. Ireland had become a bread basket for England: Irish oats and wheat kept English bread

prices low, while most of the Irish ate potatoes raised on rented land and lived at a basic, and highly vulnerable, subsistence level. Nowhere else in

Europe did people rely so heavily on one crop for survival. And the structure of land ownership meant that this crop was grown on plots so small

that almost no tenant could produce a food surplus.

Potatoes were an inadequate insurance against food shortages. More

than 65,000 people died of hunger and related diseases in 1816, the "year

without a summer." They died in part because the British authorities

chose not to ban grain exports, an effective measure in earlier dearths.

Chief Secretary Robert Peel justified this on the specious grounds that

private charity givers would relax their efforts if the government assumed

major responsibility for famine relief. In June 1817, he issued a fatuous

proclamation to the effect that "persons in the higher spheres of life

should discontinue the use of potatoes in their families and reduce the allowance of oats to their horses."''

By 1820, the potato varieties that had sustained the Irish in earlier times

were in decline. Black, Apple, and Cup potatoes were outstanding varieties, especially the Apple with its deep green foliage and roundish tubers,

which produced a rich-flavored, mealy potato likened by some to bread

in its consistency. These hardy and productive strains began to degenerate

due to indiscriminate crossbreeding in the early nineteenth century. They

gave way to the notorious Lumper, or horse potato, which had originated

as animal fodder in England. Lumpers were highly productive and easily

raised on poor soil, an important consideration when people occupied

every hectare of land. By 1835, coarse and watery Lumpers had become

the normal staple of Irish animals and the poor over much of the south

and west. Few commentators had anything polite to say about them.

Henry Dutton described them as: "more productive with a little manure

... but they are a wretched kind for any creature; even pigs, I am informed, will not eat them if they can get other kinds."12