The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (14 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

No one could resist the onslaught of an angry North Sea, which contemptuously cast aside the crude earthen dikes of the day. The hydrological and technological know-how to erect truly permanent coastal fortifications did not yet exist. The first serious and lasting coast works date to

after 1500, but even they were usually inadequate in the face of savage

hundred-year storms. Small wonder the authorities often had trouble persuading peasants to settle on easily flooded lands.

At least 100,000 people died along the Dutch and German coasts in

four fierce storm surges in about 1200, 1212-19, 1287, and 1362, in

long-forgotten disasters that rivaled the worst in modern-day

Bangladesh. The Zuider Zee in the northern Netherlands formed during the fourteenth century, when storms carved a huge inland sea from

prime farming land that was not reclaimed until this century. The

greatest fourteenth-century storm, that of January 1362, went down in

history as the Grote Mandrenke, the "Great Drowning of Men."3 A

fierce southwesterly gale swept across southern England and the English

Channel, then into the North Sea. Hurricane-force winds collapsed

church towers at Bury St. Edmunds and Norwich in East Anglia. Busy

ports at Ravenspur near Hull in Yorkshire and Dunwich on the Suffolk

shore suffered severe damage in the first of a series of catastrophes that eventually destroyed them. Huge waves swept ashore in the Low Countries. A contemporary chronicler reported that sixty parishes in the

Danish diocese of Slesvig were "swallowed by the salt sea." At least

25,000 people perished in this disaster, maybe many more: no one

made accurate estimates. The fourteenth century's increased storminess

and strong winds formed huge dunes along the present-day Dutch

coastline. Amsterdam harbor, already an important trading port, experienced continual problems with silting caused by strong winds cascading sand from a nearby dune into the entrance.

In the early 1400s, more damaging storm surges attacked densely populated shorelines. On August 19, 1413, a great southerly storm at extreme low tide buried the small town of Forvie, near Aberdeen in northeastern Scotland, under a thirty-meter sand dune. More than 100,000

people are said to have died in the great storms of 1421 and 1446.

Judging from North Atlantic Oscillation readings for later centuries,

the great storms of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were the result

of cycles of vigorous depressions that flowed across northwestern Europe

after years of more northerly passage when the NAO Index was low. The

changing signals of hydrogen isotopes from a two-hundred-meter section

of Greenland ice core GISP-2 tell us summer and winter temperatures for

the fourteenth century. This hundred-year period saw several wellmarked cycles of much colder conditions, among them 1308 to 1318, the

time of Europe's massive rains and the Great Famine; 1324 to 1329, another period of unsettled weather; and especially 1343 to 1362, when

stormy conditions in the North Sea culminated in the "Great Drowning"

and the Norse Western Settlement struggled through its exceptionally

cold winters.

Sometime between 1341 and 1363 (the date is uncertain), Norwegian

church official Ivar Bardarson sailed northward with a party of Norse

along the western Greenland coast from the Eastern to the Western Settlement, charged by local lawmen to drive away hostile skraelings who

were rumored to be attacking the farms. He found the Western Settlement deserted, a large church standing empty and no traces of any colonists. "They found nobody, either Christians or heathens, only some

wild cattle and sheep, and they slaughtered the wild cattle and sheep for

food, as much as the ships would carry."4 While Bardarson blamed elusive Inuit, whom he never encountered, his account is puzzling, for one

would assume that the marauding hunters would have killed the livestock. Bardarson seems to have visited a ghost town abandoned without

apparent reason. But modern archaeological excavations reveal a settlement that was dying on its feet from the cold.

Ever since Eirik the Red's time, the Greenlanders had lived off a medieval dairying economy just like those in their homelands. Even in good

years with warm summers and a good hay crop, they lived close to the

edge. Their survival depended on storing enough hay, dried sea mammal

flesh, and fish to tide humans and beasts over the winter months. The

Norse could usually survive one bad summer by using up the last of their

surplus the following winter. But two successive poor hay crops placed

both the animals and their owners at high risk, especially if lingering ice

restricted summer hunting and fishing. The ice-core analyses for 1343 to

1362 reveal two decades of much colder summers than usual. Such a

stretch, year after year, spelled disaster.5

The main house block of a small manor farm called Nipaatsoq tells a

grim story of the final months of its occupation. Animals and people

lived in separate rooms linked by interconnecting passages. Each spring,

the owners swept out the reeds and grass that covered the floors and emptied dung from the byres, yet the archaeologists found the debris of the

very last winter's occupation intact. No one had been left to clean up in

the spring.

Five dairy cows once occupied the manor's byre. The hooves of these

five beasts, the only part of a cow that has no food value whatsoever, were

scattered among other food remains across the lower layer of one room.

The owners had butchered the dead animals so completely that only the

hooves remained. They did this in direct violation of ancient Norse law,

which for obvious reasons prohibited the slaughter of dairy cows. In desperation, they put themselves out of the dairy business by eating their

breeding stock.

The house's main hall, with its benches and hearths, yielded numerous

arctic hare feet and ptarmigan claws, animals often hunted in winter. The

larder contained the semi-articulated bones of a lamb and a newborn calf, and the skull of a large hunting dog resembling an elkhound. The limb

bones of the same animal lay in the passageway between the hall and

sleeping chamber. All the dog bones at the manor farm came from the final occupation layer and displayed the butchery marks of carcasses cut up

for human consumption. Having first eaten their cows and then as much

small game as they could take, the Nipaatsoq families finally consumed

their prized hunting dogs.

The houseflies tell a similar tale. Centuries before, the Norse accidentally introduced a fly, Telomerina flavipes, which flourishes in dark, warm

conditions where feces are present. Telomerina could only have survived

in the warmth of the fouled floors of the main hall and sleeping quarters,

where their carcasses duly abounded. Quite different, cold-tolerant carrion fly species lived in the cool larder. Once the house was abandoned,

the cold-loving flies swarmed into the now empty living quarters as the

fires went out. Telomerina vanishes. The uppermost layer of all, accumulated after the house was empty, contains species from outside, as if the

roof had caved in.

There were no human skeletons in the house-no remains of dead

the survivors were too weak to bury, no last survivor whom no one was

left to bury. With but a few seals for the larder, the Nipaatsoq farmers

may have simply decided to leave. Where and how they ended up is

anybody's guess. Had they adopted toggling harpoons and other traditional ice-hunting technology from their Inuit neighbors a few kilometers away, they could have taken ring seal year round and perhaps

avoided the late spring crises that could envelop them even in good

years. Perhaps they had an aversion to the Inuits' pagan ways, or their

cultural roots and ideologies were simply too grounded in Europe to

permit them to adapt.

Another isolated Norse settlement, known to archaeologists as Gard

Under Sander (Farm Beneath the Sand) lay inland, close to what was once

fertile, rich meadowland just ten kilometers from Greenland's ice cap.

Farm Beneath the Sand began as a long house used first as a human

dwelling, then as an animal shed. In about 1200 the hall burnt down. Several sheep perished in the blaze. The farmers now built a centralized farmhouse, like that at Nipaatsoq, with constantly changing rooms, not all of

them in use at one time, as the stone-and-turf farm changed over more

than two centuries. Late in the 1200s, the climate deteriorated, local glaci ers advanced and the pastures sanded up. Farming became impossible and

the settlement was abandoned. After abandonment, sheep that were left

behind continued to shelter in the empty houses, as did overnighting

Thule hunters."

The Norse kept a foothold at the warmer Eastern Settlement for another 150 years. Here they lay close to the open North Atlantic, where

changing fish distributions, southern spikes of pack ice, and new economic conditions brought new explorers instead of the traditional knarrs.

Basques and Englishmen paused to fish and to trade for falcons, ivory,

and other exotic goods. But above all, they pursued whales and cod.

In the eighth century, the Catholic Church created a huge market for

salted cod and herring by allowing the devout to consume fish on Fridays,

the day of Christ's crucifixion, during the forty days of Lent and on major

feast days. The ecclesiastical authorities still encouraged fasting and forbade sexual intercourse on such occasions, also the eating of red meat, on

the grounds it was a hot food. Fish and whale meat were "cold" foods, as

they came from the water, and were thus appropriate nourishment for

holy days. But fish spoils quickly, and in the days before refrigeration,

drying and salting were about the only ways to preserve it. Dried salt cod

and salted herring quickly became the "cold" foods of choice, especially

during Lent. Salted cod kept better than either salt herring or whale meat

and was easily transported in bulk.

Cod had been a European staple since Roman times. Dried and salted

fish was light and durable, ideal hardtack for mariners and armies. In

1282, preparing to campaign in Wales, King Edward of England commissioned "one Adam of Fulsham" to buy 5,000 salted cod from Aberdeen in northeastern Scotland to feed his army. Salt cod fueled the European Age of Discovery and was known to Elizabethan mariners as the

"beef of the sea." Portuguese and Spanish explorers relied heavily on it to

provision their ships during their explorations of the New World and the

route to the Indies around the Cape of Good Hope. No one held the

stuff in high esteem. On land and at sea, people washed it down with

beer, cider, malmsey wine, or "stinking water" from wooden barrels. For centuries, thousands of fishermen, especially Basques from northern

Spain, Bretons, and Englishmen, pursued cod despite horrifying casualty

rates at sea in all weathers. A commodity with a value higher than gold,

cod sustained entire national fisheries for centuries.?

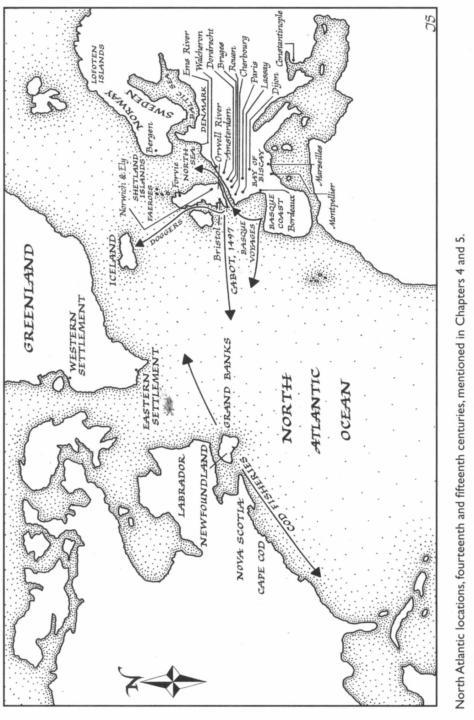

The Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua, flourishes over an enormous area of

the North Atlantic, with a modern range from the northern Barents Sea

south to the Bay of Biscay, around Iceland and the southern tip of Greenland, and along the North American coast as far south as North Carolina.

Streamlined and abundant, it grows to a large size, has nutritious, bland

flesh, and is easily cooked. It is also easily salted and dried, an important

consideration when the major markets for salt cod were far from the fishing grounds, and often in the Mediterranean. When dried, cod meat is almost 80 percent protein.