The Little Girl in the Radiator: Mum Alzheimer's & Me

Read The Little Girl in the Radiator: Mum Alzheimer's & Me Online

Authors: Martin Slevin

© Martin Slevin, 2012

The right of Martin Slevin to be identified

as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. Apart from any use

permitted under UK copyright law no part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise

circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is

published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent

purchaser

Converted to eBook by

www.ebookgenie.co.uk

The Little Girl In The Radiator

The House With The Green Kitchen Floor

To my two children, Rebecca and Daniel, who

just thought their grandmother was crazy but loved her anyway.

And to Heather, who helped me cope when no-one

else could.

Also to all the family members of Alzheimer’s

patients out there; you’re not alone.

To my Dad.

And lastly, but mostly, to my Mum.

All that follows is true.

I SHOULD make it clear right at the outset

that I have no formal medical training. I can stick a plaster on a cut finger,

but that’s about it. Everything I know about dementia, and about Alzheimer’s

disease in particular, I have either read in books or online or seen for myself

at first-hand, as it were. The observations, comments, and conclusions I make throughout

this book are my own.

In modern Britain, more money is spent on

launching a new aftershave than on researching Alzheimer’s disease; although

we’d all like the male population to smell nice, I think we would also want our

parents and grandparents to experience a quality of life during their dotage

which is currently denied them through medical ignorance.

Some names and details of the care homes my

mum went to have been changed for legal reasons, but the details of how she

suffered in the first of them are absolutely accurate.

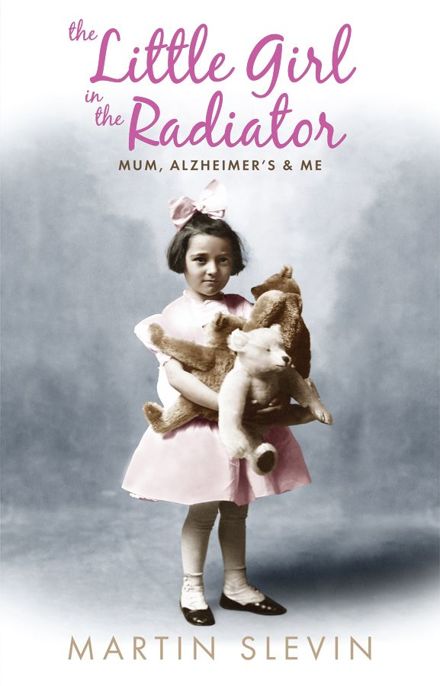

Rose Slevin, mum, as a young woman in 1945.

Rolling Up The Rug

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE IS the only medical

condition that I know of which affects the family of the patient more than it

appears to affect the patient themselves.

The long tentacles of its colourful

fantasies reach out in all directions at once, touching, clawing, caressing and

embracing all who pass within their reach, until each is drawn into the

labyrinthine tragedy and made to become an actor in the drama. While all of

this is going on, the patient continues to move through their own little world,

interacting with all of its colours, contours and characters as though nothing

had happened or changed, blissfully unaware of the emotional turmoil they are

causing in the outside universe.

If you break your leg, it incommodes you.

You

sit at home in plaster;

you

suffer and

you

deal with it: it’s

your

problem. Your family members may be slightly inconvenienced, inasmuch as they

will fetch and carry for you, but that’s about the extent of their forced

participation in your altered condition. With Alzheimer’s, it’s the other way

around. If you have Alzheimer’s disease, it becomes everyone else’s problem;

you behave as though nothing has changed, while everyone around you has to cope

with your radically altered mentality.

‘It’s like rolling up a rug,’ said the

consultant. My mother and I were sitting in the Caludon Centre, at Coventry’s Walsgrave Hospital, where she had been referred by her GP. He had suspected

the onset of dementia when mum went to his surgery to complain about a little

girl who was living inside a radiator at home, and who was whispering to her

the most disturbing things about other members of our family. When the

receptionist at the surgery heard this she had sent for the doctor, who had

come out of his consulting room into the main waiting area to find mum causing

mayhem among his other patients; she was climbing on one of the chairs and

trying to take down his curtains, because they were too short and didn’t reach

the windowsill.

Now, the specialist looked across his desk

at me and ignored my mum, who was sitting next to me, apparently unaware that

she was being discussed at all.

‘Imagine you’re standing at one end of a

long carpet,’ he said. ‘The end nearest to you represents the present, and the

other end represents your mother’s childhood. As we begin to roll up the rug,

the memories inside the roll are erased and lost forever, and her reality slips

backwards in time. The more we roll up the rug, the further back in time she

has to travel to find a point in her life that she remembers.’

I nodded slowly, trying to understand. My

mother looked at his burnt-orange curtains with a disgusted and professional

eye. They were tatty and frayed, and had probably hung on the window for years.

I knew she was thinking about how she could run up a much nicer pair for him in

no time at all. In fact, I was waiting for her to ask him for the job.

‘I want to ask your mother a few simple

questions,’ he said, finally looking at her.

She smiled back at him, amiably.

‘What year is it now, Rose?’

My mother began to frown.

‘Now that’s a hard one,’ she replied. ‘Let

me think. Is the war still on?’

The consultant smiled. ‘Do you mean the

Second World War?’

Mum nodded.

‘No, that ended in 1945,’ he said. ‘What

year is it now?’

‘Then it must be after that,’ she replied.

‘It’s 2002,’ he said.

‘Yes, that’s right,’ said mum, who would

have agreed if he had said it was 1812, and Napoleon was running France.

I squeezed her hand gently, and she turned

her head towards me and smiled.

‘I am going to ask you to remember a few

things, Rose,’ he said, ‘and then in a few minutes I will ask you to tell me

what those things were. Is that okay?’

‘Yes, that’s okay,’ said mum, looking back

at him, and smiling.

‘A pen, a newspaper, a pair of scissors, a

clock and a pair of shoes,’ he said slowly.

Mum nodded confidently.

‘Who is the Prime Minister today?’

‘Margaret Thatcher, the milk snatcher!’

announced my mum, triumphantly.

As Minister for Education – before her

election as Prime Minister of Britain in 1979 – Mrs Thatcher had been seen as

being responsible for the ending of free school milk for Britain’s children.

‘No, it’s Tony Blair at the moment,’ replied

the consultant.

‘Oh, I see,’ said mum. ‘I don’t like him.’

‘What month is it?’ asked the consultant.

‘April!’ said mum, with some certainty.

‘No, it’s August,’ said the consultant.

‘Yes, that’s right,’ said mum.

‘Now, I want you to tell me, Rose, the list

of items I gave you to remember a few minutes ago. Can you recall them?’

‘Yes, I can,’ she said. ‘A pair of

scissors.’

‘Very good.’ The consultant was nodding.

‘A bicycle, a fur hat, and a box of

chocolates!’

Mum looked very pleased with herself. The

consultant had stopped nodding.

‘I think we need to do some more tests,’ he

said.

* * * * *

There is no way of proving it now, but I

am convinced that my mother’s dementia began the day my father died. I believe

the shock of his death somehow triggered the Alzheimer’s condition in her.

My parents were married for over 50 years,

and they were never apart during that time. Each was the other’s right arm. My

dad had undergone a triple heart bypass operation 15 years before; it gave him

another decade and a half of life, but his health was broken. Slowly, very

slowly, he had become an invalid; in the last year of my father’s life, my

mother had nursed him like he was a sick child, and, even though it was seen

coming a long way off, when death finally arrived she went into shock.

My parents were from Dublin; they had met

and married there, and I was born in Ireland at a time when work and money were

scarce. The family story goes that, in 1961, when I was four years old, the

three of us were in the market in Dublin, and I asked for an apple. Mum

rummaged through her purse and found she hadn’t enough money.

‘It’s come to something when I can’t even

afford to buy my son a bloody apple!’ said my dad, and within a week we had

emigrated to Coventry. These days, like most places, it’s struggling a little,

but back then it was a thriving engineering city, the home of Jaguar cars –

where my dad worked – Massey Ferguson tractors, the black London taxi and lots

of other household names.

My mum was a talented seamstress, and she

started a little business in our two-bedroomed bungalow, making curtains and

matching bedspreads to order for people she knew. As word of her work spread,

her orders increased, and my father built her an extension out into the back

garden. This workroom was her world for the next 20 years: I can hardly recall

a time when she wasn’t back there, cutting, stitching, hand-sewing or measuring

material. Hundreds of different coloured threads stuck out of the walls on

little dowelling racks which my dad had made for her, and a long worktable and

three industrial sewing machines completed her little factory. I mention my

mother’s sewing now as it explains her interest in her doctors’ shabby old

curtains, and becomes more relevant still later on.

The months leading up to and following my

dad’s death were difficult. During the same period, my own marriage was coming

to an end, which was why I found myself, a year after he’d gone, sitting in my

mum’s kitchen and telling her I was going to move back in with her.

‘Oh, that would be lovely!’ she cried. ‘But

what about your wife, doesn’t she mind?’

‘We’ve split up,’ I said, simply.

My mother looked at me vacantly; she didn’t

seem to understand what I was saying.

‘Is she coming to stay, too?’

‘No, we’ve separated, mum,’ I said. ‘We’re

going to get a divorce. Rebecca and Daniel will continue to live there, and

I’ll move back here. I mean, if that’s all right with you?’

‘That’s great!’ she announced. ‘We can have

tea together every day!’

For various reasons I’d not visited mum that

often – once a week or so, and only then for a short while at a time – so I

hadn’t really seen the dementia ebbing and flowing through her mind like a

slowly rising tide. But as I sat there, I realised that she was now noticeably

worse than when we’d visited the consultant at the Caludon Centre a few months

earlier. I moved back over the next day or two, filling the bedroom of my

childhood with the remnants of my married life. Once I was ensconced, mum’s

decline quickly became more apparent to me.

I remember getting out of the shower one

morning as I was preparing to go to work – at the time, I was a c

ommunity

warden for Coventry City Council

. I stepped from the shower

cubicle onto the mat in the bathroom and reached over to take a fresh towel

from the rack. I was surprised when it just fell away into a series of

perfectly cut strips – about 12 of them, all exactly the same width, each

running the full length of the towel, and all laid back on the rack in perfect

symmetry, one beside the other, like a row of soldiers on parade. As I would

later learn, it is a characteristic trait of the victims of Alzheimer’s

disease, and dementia generally, that they continue obsessively to carry out

once-familiar physical tasks, perhaps in an attempt to anchor themselves in the

strange and unfamiliar new seas of their lives. In mum’s mind, she was still at

work, still cutting material to make curtains and bedding. It took me a long

time to understand that.

‘What’s happened to this towel, mum?’ I

asked, standing in the hall naked and dripping with water, and holding up the

perfect strips in either hand for my mother to see.

‘I don’t know,’ she called back from the

kitchen. ‘What are you asking me for? It must have been Peggy. Ask her.’

‘Peggy who?’ I replied.

‘Your aunt Peggy, of course,’ she said.

‘She’s always doing things like that.’

‘Mum,’ I said, softly, ‘Aunt Peggy’s been

dead for five years.’

‘She is

not

!’ insisted my mum. ‘I

spoke to her only yesterday. What are you saying things like that for?’

I thought about what the consultant had

said... The rolling up of my mother’s mental rug. If mum believed my aunt Peggy

was still alive, then she must be living in a time at least five years in the

past.

I found another towel.

* * * * *

Over the next two or three years, mum’s

decline was gradual, but inexorable. It wasn’t just her mental faculties: she

was fading away physically, too. I didn’t notice this at first, but in late

2005 I suddenly realised that she was getting very thin.

She had always been petite, and had never

put on weight despite having a good appetite. I think she lived on nervous

energy most of her adult life – she never did fewer than three things at a

time. She’d be out in her workroom making curtains or something, for instance,

and would keep popping into the kitchen to peel a bowlful of potatoes for the

family dinner, and dashing off a few lines of a letter to someone. (She was a

compulsive letter writer, of which more later.) Then she would return to the

workroom and carry on with her curtains. So she simply burned off whatever

calories she consumed.

Now, I noticed, she was getting seriously

thin. Clearly, I needed to get her eating properly. I decided to cook her a

decent meal, and opened the cupboards to start rooting around for ingredients.

Every packet, tin and box of food in the kitchen was months or even years out

of date. She’d been less than assiduous in restocking the kitchen cupboards

since my father had died.

‘All this stuff is way past its best, mum,’

I said, rummaging in a drawer for a roll of black bags.

She sat with her head in her hands and

watched me empty all the old tins and packets into the bags for the bin men to

collect on Thursday.

‘You’re going to starve me to death,’ she

sobbed. ‘Wait until your father gets home. He’ll have something to say about

this!’

She used to say that to me when I had been a

naughty child, and it still made me feel uncomfortable. Dad had always been the

one to punish me, to stop my pocket money, to send me to my room. I suppose I

was a handful as a kid, and I always seemed to be waiting for him to come home.

‘You can’t eat this stuff,’ I said. ‘Half of

it would give you food poisoning.’

Mum shook her head. ‘Your father won’t be

happy.’

‘Dad’s dead, mum,’ I replied, bluntly. Too

bluntly.

She looked at me with disgust in her eyes.

‘How could you be so cruel as to say that to

me? When I think of how much your father loves you, and all the things he does

for you.’

‘I know all that, mum, and I loved him too.

But he’s dead now, don’t you understand that?’