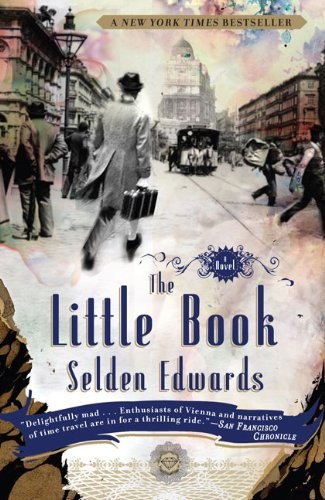

The Little Book

Authors: Selden Edwards

Table of Contents

DUTTON

Published by Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Published by Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) · Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL,

England · Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books

Ltd) · Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a

division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) · Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India · Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale,

North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) · Penguin Books (South

Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) · Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL,

England · Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books

Ltd) · Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a

division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) · Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi—110 017, India · Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale,

North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) · Penguin Books (South

Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Published by Dutton, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First printing, August 2008

Published by Dutton, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First printing, August 2008

Copyright © 2008 by Selden Edwards

All rights reserved

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Edwards, Selden.

The little book / Selden Edwards.

p. cm.

Edwards, Selden.

The little book / Selden Edwards.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-0-525-95061-5

1. Rock musicians—Fiction. 2. Time travel—Fiction. 3. Vienna (Austria)—Fiction.

4. Austria—History—1867-1918—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3605.D8985F56 2008

813’.6—dc22 2007045785

4. Austria—History—1867-1918—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3605.D8985F56 2008

813’.6—dc22 2007045785

PUBLISHER’S NOTE: This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For Gaby

This is the story of how, through a dislocation in time, my son, Frank Standish Burden III, the famous American rock-and-roll star of the 1970s, found himself in Vienna in the fall of 1897. It is a complicated story, full of extraordinary characters and wild improbabilities. Rather than dwell on those improbabilities or the parts that require more thought and explanation, I will simply tell you what I know exactly as I know it and let you sort out the pieces for yourself, forgiving a ninety-year-old woman her various lapses of memory. As an aged poet once said, “I do not remember all the details, but what I remember, I do remember perfectly.” And you will forgive this very subjective narrator her need to describe herself in the third person, as just another character in this remarkable tale. It is, after all, my son who is the center of this narrative. The world, of course, knew him as Wheeler, a name he acquired in the early 1950s, playing boys’ baseball in the Sacramento Valley of California, exactly how we will come to later. So Wheeler it will be, as I reconstruct for you his story.

Flora Zimmerman Burden

Feather River, California, 2005

Feather River, California, 2005

PART ONE

T

he Connectedness of All Things

he Connectedness of All Things

1

Arrival

Wheeler Burden did not think of visiting Berggasse 19 until the third day in Vienna, or at least there is no mention of it in the journal he kept with meticulous care from almost the moment of his arrival. The first days he spent adjusting, you might say, to the elation of newness and the spectacle of this city he knew so well in theory but had never actually visited. Then the practicalities settled on him, followed by a deep feeling of displacement. Wheeler was a long way from home with no means of either identification or support. But before the gravity of the situation set in, he was almost able to enjoy himself. Much of the first day, of course, he was busy marveling at his mere presence in such a magnificent and imperial city. It was 1897 Vienna, after all. The first hour, we learn from the journal, he spent clearing the fog from his mind and pulling himself painfully back to full awareness, emerging from the miasma of what seemed like a long uneasy sleep, and from the catastrophic precipitating event he was nowhere near ready to remember.

In the first moments Wheeler could only stare vacantly at the handsome men in dark coats and top hats, finely adorned women in long dresses with tightly corseted waists and well-defined

poitrines

, military officers in ornate and colorful regalia, workers carrying lunch boxes. Everywhere there were horse-drawn carriages of all sorts, and tall, elegant marble façades of the grand buildings for which Vienna at the end of the century had become renowned.

poitrines

, military officers in ornate and colorful regalia, workers carrying lunch boxes. Everywhere there were horse-drawn carriages of all sorts, and tall, elegant marble façades of the grand buildings for which Vienna at the end of the century had become renowned.

You do need to know that Wheeler Burden had never been to Vienna per se but had traveled there many times before in his mind. He could speak German as a result of a natural fluency with languages, and he had a general grasp of the manner in which a young man in fin de siècle Vienna was expected to carry himself, both a result of what now seemed like careful training in the hands of his wise old mentor, the Venerable Haze, whom we will encounter momentarily. In fact, after some reflection, you might conclude that, as with so many heroes who are invited on extraordinary journeys, Wheeler’s way had been prepared.

Some time after his mysterious arrival, in pulling together his initial impressions, Wheeler would detail in his journal his first moments on the Ringstrasse, the broad and magnificent boulevard that encircled the city, as awaking from a great sleep, floating between oblivion and consciousness. Anesthesia was an experience he had been through twice—once having his tonsils removed as a child and once in adulthood in 1969, during surgery to repair a spleen ruptured by an angry Hell’s Angel at a well-publicized rock-concert riot. This time he was not lying inertly in a hospital room blinking at sterile walls and unfamiliar nurses, but rather coming to his senses walking along a magnificent, wide boulevard, gaping at finely dressed passersby and massive, grandly detailed buildings.

His first recollections were ones of ambling aimlessly, smiling, gazing absently at these spectacular edifices with awe and elation, as if the mechanism that had delivered him to this fabulous place had carried with it, like anesthesia, the complete dismantling of any worldly concern.

He must have entered, he figured later, somewhere near the Danube Canal and circled half the old city before enough consciousness descended to demand a verification of place and time. Wheeler found himself drawn to a newsstand, where he picked up his first newspaper. It was then that he realized there was no other city it could have been, really. All of the impressions that led to this inevitable conclusion were rooted in the Haze’s vivid descriptions of the time and place, preserved in his famous “Random Notes,” but of course Wheeler was at the moment much more concerned with practical matters than he was with the peculiar coincidence of winding up in exactly the time and place that he had heard described so often.

First, he had to do something about his clothes. He was staring at the Viennese, predictable given his circumstance, but they were staring back, which, again given his circumstance as a stranger in a strange land, was not good. People staring, you might know, was certainly nothing new to my son. With his long hair and Wild Bill Hickok mustache, Wheeler Burden was on

People

magazine’s ten most recognizable list five years running in the mid 1970s, and, in the words of one of his grammar school teachers, had been “something of a spectacle” all his life. The Viennese focused their suspicious attention on him as he passed, not recognizing him specifically, as strollers in the 1970s would have, but simply wondering what a man in his late forties of his appearance, dressed as he was, was doing on the Ringstrasse. The style of the times and the crisp morning air made being out in shirtsleeves inappropriate, not to mention uncomfortable. This attention was giving him a deep sense of foreboding.

People

magazine’s ten most recognizable list five years running in the mid 1970s, and, in the words of one of his grammar school teachers, had been “something of a spectacle” all his life. The Viennese focused their suspicious attention on him as he passed, not recognizing him specifically, as strollers in the 1970s would have, but simply wondering what a man in his late forties of his appearance, dressed as he was, was doing on the Ringstrasse. The style of the times and the crisp morning air made being out in shirtsleeves inappropriate, not to mention uncomfortable. This attention was giving him a deep sense of foreboding.

Since strangeness, not notoriety, was drawing the unwanted attention in this situation, one in which anonymity above all was to be wished, at least until he had his bearings, he decided that doing something about appearance was his first priority.

No matter how much a more cautious person—his mother, say—might have advised looking before leaping, he felt he had to act. So, just as he had made his way around the Ring to the area of the opera house, he was drawn into his first action, a fateful one, one that set in motion everything that was to follow and established him indelibly as the central character in this story.

Other books

Billionaire Secrets of a Wanglorious Bastard by Auld, Alexei

Morte by Robert Repino

Magic Hoffmann by Arjouni, Jakob

My Fake Fiancé by Lisa Scott

Pegasi and Prefects by Eleanor Beresford

The Amulet by Lisa Phillips

Locket full of Secrets by Dana Burkey

Fallen Pride (Jesse McDermitt Series) by Wayne Stinnett

John Lennon: The Life by Philip Norman

Beyond the Hurt by Akilah Trinay