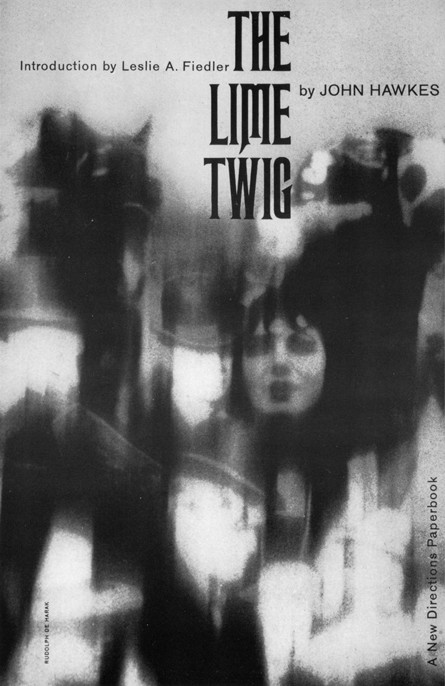

The Lime Twig

For Maclin Guerard

BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER

Everyone knows that in our literature an age of experimentalism is over and an age of recapitulation has begun; and few of us, I suspect, really regret it. How comfortable it is to be interested in literature in a time of standard acceptance and standard dissent—when the only thing more conventionalized than convention is revolt. How reassuring to pick up the latest book of the latest young novelist and to discover there familiar themes, familiar techniques—accompanied often by the order of skill available to the beginner when he is able (sometimes even with passionate conviction) to embrace received ideas, exploit established forms. Not only is the writing of really new books a perilous pursuit, but even the reading of such books is beset with dangers; and it is for this reason, I suppose, that readers are secretly grateful to authors content to rewrite the dangerous books of the past. A sense of

déjà vu

takes the curse off the whole ticklish enterprise in which the writer engages, mitigates the terror and truth which we seek in his art at the same time we cravenly hope that it is not there.

John Hawkes neither rewrites nor recapitulates, and, therefore, spares us neither terror nor truth. It is, indeed, in the interests of the latter that he endures seeming in 1960 that unfashionable and suspect stereotype, the “experimental writer.” Hawkes’ “experimentalism” is, however, his own rather than that of yesterday’s avantgarde rehashed; he is no more an echoer of other men’s revolts than he is a subscriber to the recent drift toward neo-middlebrow sentimentality. He is a lonely eccentric, a genuine unique—a not uncommon American case, or at least one that used to be not uncommon; though now, I fear, loneliness has become as difficult to maintain among us as failure. Yet John Hawkes has managed both, is perhaps (after the publication of three books and on the verge of that of the fourth) the least read novelist of substantial merit in the United States. I recall a year or so ago coming across an ad in the

Partisan Review

in which Mr. Hawkes’ publisher was decrying one of those exclusions which have typically plagued him. “Is

Partisan

,” that publisher asked, “doing right by its readers when it consistently excludes from its pages the work of such writers as Edward Dahlberg, Kenneth Patchen, Henry Miller, John Hawkes and Kenneth Rexroth?”

But God knows that of all that list only Hawkes really

needs

the help of the

Partisan Review

. Miller has come to seem grandpa to a large part of a generation; while the two Kenneths are surely not without appropriate honors and even Dahlberg has his impassioned exponents. Who, however, reads John Hawkes? Only a few of us, I fear, tempted to pride by our fewness, and ready in that pride to believe that the recalcitrant rest of the world doesn’t deserve Hawkes, that we would do well to keep his pleasures our little secret. To tout him too widely would be the equivalent of an article in

Holiday

, a note in the travel section of the

Sunday Times

, might turn a private delight into an attraction for everybody. Hordes of the idly curious might descend on him and us, gaping, pointing—and bringing with them the Coca-Cola sign, the hot-dog stand. They’ve got Ischia now and Mallorca and Walden Pond. Let them leave us Hawkes! But, of course, the tourists would never really come; and who would be foolish enough in any case to deny to anyone daylight access to those waste places of the mind from which no one can be barred at night, which the least subtle visit in darkness and unknowing. Hawkes may be an unpopular writer, but he is not an esoteric one; for the places he defines are the places in which we all live between sleeping and waking, and the pleasures he affords are the pleasures of returning to those places between waking and sleeping.

He is, in short, a Gothic novelist; but this means one who makes terror rather than love the center of his work, knowing all the while, of course, that there can be no terror without the hope for love and love’s defeat. In

The Cannibal, The Beetle Leg

, and

The Goose on the Grave

he has pursued through certain lunar landscapes (called variously Germany or the American West or Italy) his vision of horror and baffled passion; nor has his failure to reach a wide audience shaken his faith in his themes. In

The Lime Twig

he takes up the Gothic pursuit once more, though this time his lunar landscape is called England; and the nightmare through which his terrified protagonists flee reaches its climax at a race meeting, where gangsters and cops and a stolen horse bring to Michael Banks and his wife the spectacular doom which others of us dream and wake from, relieved, but which they, improbably live.

It is all, on one level, a little like a thriller, a story, say, by Graham Greene; and, indeed, there is a tension in

The Lime Twig

absent from Hawkes’ earlier work: a pull between the aspiration toward popular narrative (vulgar, humorous, suspenseful) and the dedication to the austerities of highbrow horror. Yet Hawkes’ new novel finally avoids the treacherous lucidity of the ordinary shocker, the kind of clarity intended to assure a reader that the violence he relives destroys only certain characters in a book, not the fabric of the world he inhabits. In a culture where even terror has been so vulgarized by mass entertainers that we can scarcely believe in it any longer, we hunger to be persuaded that, after all, it really counts. For unless the horror we live is real, there is no point to our lives; and it is to writers like Hawkes that we turn from the wholesale slaughter on T.V. to be convinced of the reality of what we most fear. If

The Lime Twig

reminds us of

Brighton Rock

, which in turn reminds us of a movie by Hitchcock, it is of

Brighton Rock

recalled in a delirium or by a drowning man

—Brighton Rock

rewritten by Djuna Barnes. Hawkes, however, shares the effeteness of Djuna Barnes’s vision of evil no more than he does the piety of Greene’s vision of sin. His view avoids the aesthetic and the theological alike, since it deals with the mysteries neither of the world of art nor of the spirit—but only with the immitigable mystery of the world of common experience. It is not so much the fact that love succumbs to terror which obsesses Hawkes as the fact that love breeding terror is itself the final terror. This he neither denies nor conceals, being incapable of the evasions of sentimentality: the writer’s capitulation before his audience’s desire to be deceived, his own to be approved. Hawkes’ novel makes painfully clear how William Hencher’s love for his mother, dead in the fire-bombings of London, brings him back years later to the lodgings they once shared—a fat man with elastic sleeves on his thighs, in whom the encysted small boy cannot leave off remembering and suffering. But in those lodgings he discovers Banks and his wife Margaret, yearns toward them with a second love verging on madness, serves them tea in bed and prowls their apartment during their occasional absences, searching for some way to bind them, his memories, and his self together. “I found,” he reports of one such occasion, “her small tube of cosmetic for the lips and, in the lavatory, drew a red circle with it round each of my eyes. I had their bed to myself while they were gone.” It is, however, Hencher’s absurd and fetishistic passion which draws Michael Banks out of the safe routine of his life into crime, helps, that is, to turn a lifetime of erotic daydreaming about horses into the act of stealing a real race horse called Rock Castle.

And the end of it all is sheer terror: Hencher kicked to a pulp in a stable; Margaret Banks naked beneath the shreds of a hospital gown and lovingly beaten to death; Michael, screwed silly by all his nympholeptic dreams become flesh, throwing himself under the hooves of a field of horses bunched for the final turn and the stretch! What each of Hawkes’ doomed lovers has proposed to himself in fantasy—atrocious pleasure or half-desired indignity—he endures in fact. But each lover, under cover of whatever images, has ultimately yearned for his own death and consequently dies; while the anti-lovers, the killers, whose fall guys and victims the lovers become, having wished only for the death of others, survive: Syb, the come-on girl, tart and teaser; Little Dora, huge and aseptically cruel behind her aging school-marm’s face; and Larry, gangster-in-chief and cock-of-the-house, who stands stripped toward the novel’s end, indestructible in the midst of the destruction he has willed, a phallic god in brass knuckles and bulletproof vest.

They cheered, slapping the oxen arms, slapping the flesh, and cheered when the metal vest was returned to him—steel and skin—and the holster was settled again but in an armpit naked now and smelling of scented freshener.

Larry turned slowly round so they could see, and there was the gun’s blue butt, the dazzling links of steel the hairless and swarthy torso. …

“For twenty years,” shouted Dora again through the smoke opaque as ice, “for twenty years I’ve admired that! Does anybody blame me.” Banks listened and … for a moment met the eyes of Sybilline, his Syb, eyes in a lovely face pressed hard against the smoothest portion of Larry’s arm, which—her face with auburn hair was just below his shoulder—could take the punches …

And even these are bound together in something like love.

Of all the hook’s protagonists, only Sidney Slyter is without love; half dopester of the races, half amateur detective, Sidney is at once a spokesman for the novelist and a parody of the novelist’s role, providing a choral commentary on the action, which his own curiosity spurs toward its end. Each section of the novel opens with a quotation from his newspaper column,

Sidney Slyter says

, in which the jargon of the sports page merges into a kind of surrealistic poetry, the matter of fact threatens continually to become hallucination. But precisely here is the clue to the final achievement of Hawkes’ art, his detachment from that long literary tradition which assumes that consciousness is continuous, that experience reaches us in a series of framed and unified scenes, and that—in life as well as books—we are aware simultaneously of details and the context in which we confront them.

Such a set of assumptions seems scarcely tenable in a post-Freudian, post-Einsteinian world; and we cling to it more, perhaps, out of piety toward the literature of the past than out of respect for life in the present. In the world of Hawkes’ fiction, however, we are forced to abandon such traditional presumptions and the security we find in hanging on to them. His characters move not from scene to scene but in and out of focus; for they float in a space whose essence is indistinctness, endure in a time which refuses either to begin or end. To be sure, certain details are rendered with a more than normal, an almost painful clarity (quite suddenly a white horse dangles in mid-air before us, vividly defined, or we are gazing close up, at a pair of speckled buttocks), but the contexts which give them meaning and location are blurred by fog or alcohol, by darkness or weariness or the failure of attention. It is all, in short, quite like the consciousness we live by but do not record in books—untidy, half-focused, disarrayed.

The order which retrospectively we

impose

on our awareness of events (by an effort of the will and imagination so unflagging that we are no more conscious of it than of our breathing) Hawkes decomposes. For the sake of art and the truth, he dissolves the rational universe which we are driven, for the sake of sanity and peace, to manufacture out of the chaos of memory, impression, reflex and fantasy that threatens eternally to engulf us. Yet he does not abandon all form in his quest for the illusion of formlessness; in the random conjunction of reason and madness, blur and focus, he finds occasions for wit and grace. Counterfeits of insanity (automatic writing, the scrawls of the drunk and doped) are finally boring; while the compositions of the actually insane are in the end merely documents, terrible and depressing. Hawkes gives us neither of these surrenders to unreason but rather reason’s last desperate attempt to know what unreason is; and in such knowledge there are possibilities not only for poetry and power but for pleasure as well.

Goshen, Vermont

June, 1960

Dreary Station Severely Damaged During Night …

Bomber Crashes in Laundry Court …

Fires Burning Still in Violet Lane

…

Last night Blood’s End was quiet; there was some activity in Highland Green; while Dreary Station took the worst of Jerry’s effort. And Sidney Slyter has this to say: a beautiful afternoon, a lovely crowd, a taste of bitters, and light returning to the faces of heroic stone—one day there will be amusements everywhere, good fun for our mortality, and you’ll whistle and flick your cigarette into an old crater’s lip and with your young woman go off to a fancy flutter at the races. For Sidney Slyter was recognized last night. The man was in a litter, an old man propped up in the shelter at Temple Place. I pushed my helmet back and gave him a smoke and all at once he said: “You’ll write about the horses again, Sidney! You’ll write about the nags again all right…” So keep a lookout for me. Because Sidney Slyter will be looking out for you. …

Have you ever let lodgings in the winter? Was there a bed kept waiting, a comer room kept waiting for a gentleman? And have you ever hung a cardboard in the window and, just out of view yourself, watched to see which man would stop and read the hand-lettering on your sign, glance at the premises from roof to little sign—an awkward piece of work—then step up suddenly and hold his finger on your bell? What was it you saw from the window that made you let the bell continue ringing and the bed go empty another night? Something about the eyes? The smooth white skin between the brim of the bowler hat and the eyes?

Or perhaps you yourself were once the lonely lodger. Perhaps you crossed the bridges with the night crowds, listened to the tooting of the river boats and the sounds of shops closing on the far side. Perhaps the moon was behind the cathedral. You walked in the cathedral’s shadow while the moon kept shining on three girls ahead. And you followed the moonlit girls. Or followed a woman carrying a market sack, or followed a slow bus high as a house with a saint’s stone shadow on its side and smoke coming out from between the tires. Then a turn in the street and broken glass at the foot of a balustrade and you wiped your forehead. And standing still, shoes making idle noise on the smashed glass, you took the packet from inside your coat, unwrapped the oily paper, and far from the tall lamp raised the piece of hot white fish to your teeth.

You must have eaten with your fingers. And you were careful not to lick your lips when you stepped out into

the light once more and felt against your face the air waves from the striking of the clock high in the cathedral’s stone. The newspaper—it was folded to the listings of single rooms—fell from your coat pocket when you drank from the bottle. But no matter. No need for the rent per week, the names of streets. You were walking now, peering in the windows now, looking for the little signs. How bloody hard it is to read hand-lettering at night. And did your finger ever really touch the bell?

I wouldn’t advise Violet Lane—there is no telling about the beds in Violet Lane—but perhaps in Dreary Station you have already found a lodging good as mine, if you were once the gentleman or if you ever took a tea kettle from a lady’s hands. A fortnight is all you need. After a fortnight you will set up your burner, prepare hot water for the rubber bottle, warm the bottom of the bed with the bag that leaks round its collar. Or you will turn the table’s broken leg to the wall, visit the lavatory in your robe, drive a nail or two with the heel of your boot. After a fortnight they don’t evict a man. All those rooms—number twenty-eight, the one the incendiaries burned on Ash Wednesday, the final cubicle that had iron shutters with nymphs and swans and leaves—all those rooms were vacancies in which you started growing fat or first found yourself writing to the lady in the

Post

about salting breast of chicken or sherrying eggs. A lodger is a man who does not forget the cold drafts, the snow on the window ledge, the feel of his knees at night, the taste of a mutton chop in a room in which he held his head all night.

It was from Mother that I learned my cooking.

They were always turning Mother out onto the street. Our pots, our crockery, our undervests, these we kept in cardboard boxes, and from room to empty room we carried them until the strings wore out and her garters and medicines came through the holes. Our boxes lay in spring rains, they gathered snow. Troops, cabmen, bobbies passed them moldering and wet on the street. Once, dried out at last and piled high in a dusty hall, our boxes were set afire. Up narrow stairs and down we carried them, over steps with spikes that caught your boot heels and into small premises still rank with the smells of dead dog or cat. And out of her greasy bodice the old girl paid while I would be off to the unfamiliar lavatory to fetch a pull of tea water in our black pot.

“Here’s home, Mother,” I would say.

Then down with the skirt, down with the first chemise, off with the little boots. And, hands on the last limp bows: “You may manipulate the screen now, William.” It was always behind the boxes, a screen like those standing in theater dressing rooms or in the wards of hospitals, except that it was horsehair brown and filled with holes from her cigarette. And each time we changed our rooms, whether in the morning or midday or dusk, I would set up the screen first thing and behind it Mother would finish stripping to the last scrap of girded rag—the obscene bits of makeshift garb poor old women carry next their skin—and after discarding that would wrap herself in the tawny dressing gown and lie straight upon the single bed while I worked at the burner’s pale and rubbery

flame. And beyond our door and before the tea was in the cup, we would hear the footsteps, the cheap bracelet tinkling a moment at the glass, would hear the cold fingers lifting down the sign.

Together we took our lodgings, together we went on the street. Fifteen years of circling Dreary Station, she and I, of discovering footprints in the bathtub or a necktie hanging from the toilet chain, or seeing flecks of blood in the shaving glass. Fifteen years with Mother, going from loft to loft in Highland Green, Pinky Road—twice in Violet Lane—and circling all that time the gilded cherubim big as horses that fly off the top of the Dreary Station itself.

If you live long enough with your mother you will learn to cook. Your flesh will know the feel of cabbage leaves, your bare hands will hold everything she eats. Out of the evening paper you will prepare each night your small and tidy wad of cartilage, raw fat, cold and dusty peels and the mouthful—still warm—which she leaves on her plate. And each night as softly as you can, wiping a little blood off the edge of the apron, you will carry your paper bundle down the corridor and into the coldness and falling snow where you will deposit it, soft and square, just under the lid of the landlady’s great pail of slops. Mother wipes her lips with your handkerchief and you set the rest of the kidneys on the sooty and frozen window ledge. You cover the burner with its flowered cloth and put the paring knife, the spoon, the end of bread behind the little row of books. There is a place for the pot in the drawer beside the undervests.

In one of the alleys off Pinky Road I remember a little boy who wore black stockings, a shirt ripped off the shoulder, a French sailor’s hat with a red pompom. The whipping marks were always fresh on his legs and one cheekbone was blue. A flying goose darkened the mornings in that alley off Pinky Road, the tar buildings were slick with gray goose slime. After the old men and apprentices had left for the high bridges and little shops the place was empty and wet and dead as a lonely dockyard. Then behind the water barrel you could see the boy and his dog.

Each morning when the steam locomotives began shrieking out of Dreary Station the boy knelt on the stones in the leakage from the barrel and caught the puppy by its jowls and rolled its fur and rubbed its ears between his fingers. Alone with the tar doors dripping and the petrol and horse water drifting down the gutters, the boy would waggle the animal’s fat head, hide its slow shocked eyes in his hands, flop it upright and listen to its heart. His fingers were always feeling the black gums or the soft wormy little legs or quickly freeing and pulling open the eyes so that he, the thin boy, could stare into them. No fields, sunlight, larks—only the stoned alley like a footpath on a quay down which a black ship might come sailing if the wind held, and down beneath the mists coming off the dead steeple-cocks the boy with the poor dog in his arms and loving his close scrutiny of the nicks in its ears, tiny channels over the dog’s brain, pictures he could find on its purple tongue, pearls he could discover between the claws. Love

is a long close scrutiny like that. I loved Mother in the same way.

I see her: it is just before the end; she is old; I see her through the red light of my glass of port. See the yellow hair, the eyes drying up in the comers. She laughs and jerks her head but the mouth is open, and that is what I see through the glass of port: the laughing lips drawn round a stopper of darkness and under the little wax chin a great silver fork with a slice of bleeding meat that rises slowly, slowly, over the dead dimple in the wax, past the sweat under the first lip, up to the level of her eyes so she can take a look at it before she eats. And I wait for the old girl to choke it down.

But there is a room waiting if you can find it, there is a joke somewhere if you can bring it to your lips. And my landlord, Mr. Banks, is not the sort to evict a man for saying a kind word to his wife or staying in the parlor past ten o’clock. His wife, Margaret, says I was a devoted son.

Yes, devoted. I remember fifteen years of sleeping, fifteen years of smelling cold shoes in the middle of the night and waiting, wondering whether I smelled smoke down the hallway to the toilet or smelled smoke coming from the parlor that would bum like hay. I think of the whipped boy and his dog abed with him and that’s what devotion is: sleeping with a wet dog beneath your pillow or humming some childish time to your mother the whole night through while waiting for the plaster, the beams, the glass, the kidneys on the sill to catch fire. Margaret’s estimation of my character is correct. Heavy men are

most often affectionate. And I, William Hencher, was a large man even then.

“Don’t worry about it, Hencher,” the captain said. “We’ll carry you out if we have to.” On its cord the bulb was circling round his head, and across the taverns and walls and craters of Dreary Station came the sirens and engines of the night. Sometimes, at the height of it, the captain and his man—an ex-corporal with rotten legs who wore a red beret and was given to fainting in the hall—went out to walk in the streets, and I would watch them go and wait, watch the searchlights fix upon the wounded cherubim like giants caught naked in the sky, until I heard them swearing in the hall again and, from the top of the stair, an unfamiliar voice crying, “Shut the door. Oh, for the love of bleeding Hell, come shut the door.”

We were so close to the old malevolent station that I could hear the shifting of the sandbags piled round it and could hear the locomotives shattering into bits of iron. And one night wouldn’t a cherubim’s hand or arm or curly head come flying down through our roof? Some dislodged ball of saintly brass palm or muscle or jagged neck find its target in Lily Eastchip’s house? But I wasn’t destined to die with a fat brass finger in my belly.

To think that Mr. and Mrs. Banks—Michael and Margaret—were only children then, as small and crouching and black-eyed as the boy with the French sailor’s hat and the dog. It is a pity I did not know them then: somehow I would have cared for them.

Such things don’t want forgetting. When they anchored

a barrage balloon over number twenty-eight—how long it was since we had been evicted from that room—and when the loft in Highland Green had burned Ash Wednesday, and during those days when the water would curl a horse’s lip and somebody’s copy of

The Vicar of Wakefield

was run over by a fire truck outside my door, why then there was plenty of soot and scum the memory could not let go of.

There was Lily Eastchip with bird feathers round her throat and a dusty rag up the tiny pearl lacing of her sleeve; there was the captain dishonorably mustered from the forces; there was the front of our narrow lodging which the firemen kept hosing down for luck; there was the pink slipper left caught by its heel in the stairway rungs and hanging toe first into the dark of that dry plaster hall. And there were our boxes with broken strings, piled in the hallway and rising toward the slipper, all the cartons I had not the heart to drag to Mother’s room. So I see the pasty corporal—Sparrow was his name—rubbing together the handles of his canes, I see Miss Eastchip serving soup, I see Mother’s dead livid face. And I shall always see the bomber with its bulbous front gunner’s nest flattened over the cistern in the laundry court.

Margaret remembers none of it and Mr. Banks, her husband, is not a talker. But Miss Eastchip’s brother went down in his spotter’s steeple, tin hat packed red with embers and both feet in the enormous boots burning with a gas-blue flame. Lily got word of it the eve he fell and with the duster hanging down her wrist and the tears on

her cheek she looked as if someone had touched a candle to her nightdress in the dark of our teatime. She stood behind the captain’s chair whispering, “That’s the end for me, the end for me,” while the bearer of the news merely sat for a moment, teacup rattling in the saucer and helmet gripped between his knees.

“Well, sorry to bring distressing information,” the warden had said. “You’d better keep the curtains on good tonight. We’re in for it. I’m afraid.”

A pale snow was coming down when he passed my window—a black square-shouldered man—and I saw the dark shape of him and the gleam off the silvery whistle caught in his teeth. Somebody laid the cold table, and far-off we heard the first dull boom and breath, as if they had blown out a candle as tall as St. George’s spire.

“Good night, Hencher. …”

“Good night, Captain. Mother gave you the salts for Lily, did she?”

“She did. And—Hencher—if anything uncommon occurs in the night, you can always give me a signal on the pipes.”