The life of Queen Henrietta Maria (21 page)

Read The life of Queen Henrietta Maria Online

Authors: Ida A. (Ida Ashworth) Taylor

Tags: #Henrietta Maria, Queen, consort of Charles I, King of England, 1609-1669

secure so inadequate a return. For obtaining a clear conception of her true point of view at this juncture there are exceptional means at hand. In the narrative declared by Madame de Motteville to have been taken down from her lips, and which there is no reason to doubt was substantially her own, 1 she recapitulated the events leading up to the final catastrophe. The abrege thus supplied may not be of much importance historically, but it furnishes curious and interesting evidence, not to be found elsewhere, of Henrietta's own attitude, and for this reason alone it would be worth while, in her biography, to dwell upon it in some detail.

In accounting to her friend for the origin of the Scottish troubles, she attributed to the Archbishop, " at heart a good Catholic," the desire with which the King was inspired to re-establish the liturgy in the northern portion of his dominions—relating further how, at the time when the book prepared was to be despatched to Scotland, Charles had one evening brought a copy of it to her apartment, and had begged her to read it, telling her that he would like her to see how similar were their beliefs. That he should have entered upon the attempt to force upon the fierce and sturdy Protestantism of the north a volume calculated to impress this fact upon his Catholic wife, is another proof of his utter incapability of measuring and estimating the forces arrayed against him. The light in which the Queen regarded the

1 J'ai su par elle-m€me le commencement et la suite de ses disgraces ; et comme elle m'a fait 1'honneur de me les center exactement dans un lieu solitaire ou la paix et le repos regnoient sans aucun trouble, j'en ai e"crit les plus remarquables evenements, que j'ai cru devoir mettre ici. . . . Elle s'est occupee quelques jours a se donner la peine de me faire le r6cit de ses malheurs avec assez d'ordre et de nettete pour les pouvoir retenir, et j'ai ecrit tous les soirs fort exactement ce qu'elle m'a conte", sans rien changer au fond de cette histoire. — Memoires de Madame de Motteville.

unfortunate compilation, considered by her to be the raison d'etre of the initial revolt, is contained in her observation that, having reached Scotland, " this fatal book " gave rise at once to much disturbance. Her conception of the passionate religious convictions which lent its power to the Puritan opposition as well in Scotland as in England, is to be inferred from the account given by Madame de Motteville of the combination formed in the following year between the political malcontents of both countries and a third faction described as " a sect called Ana-Baptists, otherwise indifFerentists, who permit every religion and know not which is their own," every man being heretic in England a sa mode.

Charles' attempt at religious coercion was met by the determined resistance of all classes alike, the nobility and gentry, with comparatively few exceptions, joining hands with the common people in defence of their ecclesiastical rights. The Council itself was half-hearted, or more than half-hearted, in its desire to uphold the royal authority. Petitions poured in from every quarter. Commissioners were appointed to represent the nation in Edinburgh, and Charles' commands that all strangers should leave the capital were practically disregarded. His further directions that the Council of State should remove to another place raised so great a storm of protest that Council, Provost, and Bishop were compelled to invoke the protection of the King's opponents. By November a permanent body of commissioners had been chosen to replace those selected in haste and to await the King's reply to the General Supplication concerning the affairs of the Church, all that had so far been elicited from him being his abhorrence of Popery and desire to advance religion as professed in Scotland. Thus 1637 drew towards its close in the northern kingdom.

At court the autumn had passed uneventfully away. The Percy interest was as strong as ever on the Queen's side, and letters from the younger brother, Henry Percy, to Lord Leicester, ambassador in Paris and married to a sister of his own, kept the absentee informed of matters at Whitehall. In these communications the Queen is Celia, Charles Arviragus, and Leicester himself Apollo ; and it is evident that in August an attempt was being made to obtain, through Henrietta, some coveted post, since Percy is found deploring the fact that, Celia's intentions having become known, it was likely to give a great distaste to Arviragus to hear how they ordered those things without his knowledge. A month later it is reported that "Celia hath done tour d'amis;" and that though Percy himself had been forced to become the bearer of a letter to her, probably from one of his sisters, couched in language less mild than he would have desired, he had caused the Queen to consider it as proceeding from a kind wife, and Arviragus had known nothing of it.

Whilst such intrigues were the matters of principal interest at court, in the country at large resistance to illegal taxation was -gathering to a head. Ship-money might be needed. It might, further, in view of the country's necessities, be necessary to enforce its payment. But it was for Parliament to decide the question. The matter at issue between King and country was neither the nature of the tax nor the uses to which it was applied, but the right of the Crown to raise it in the absence of the authorisation of the representatives of the people. It was a case, not of money, but of principle. Throughout the summer the opposition had been carried on. The refusal of Hampden to pay the tax had been selected as a test case. Through November and December his trial was protracted ; but not till some months later was

the decision of the judges made known, when seven out of twelve declared in favour of the King's claim. Though by a narrow majority, Charles had won. But it is said that the speeches of the counsel for the defence, with the arguments of the judges on the popular side, freely circulated amongst the people, more than counteracted the effect of the technical victory obtained by the Crown.

In the condition of things thus epitomised the year 1638 opened. The struggle, for constitutional rights in England, in Scotland for religious privileges, was agitating both nations. Discontent, especially in the north, was rapidly assuming the character of disaffection. King and nation were more and more openly opposed. Yet, even at this stage, few persons were probably clear-sighted enough to discern the signs of the times, or to foresee the magnitude of the approaching conflict, and Henrietta, in particular, would not entertain serious apprehensions as to its issue.

Life at court still went on as if no thunderstorm was gathering without. A letter addressed to Wentworth in February by one of his London newsagents is as full of gossip as if no weightier matters claimed consideration than the King's 'Twelfth Night masque or the authorship of an anonymous paper. The masque had been less well attended than usual, owing perhaps to the unusual cold, or to the performance having been fixed for a Sunday, or possibly to other causes. A reflection of the religious strife then being carried on at court is found in the report of a suggestion made in Council to the effect that all eldest sons should be removed from the wardship of Catholic parents and bred up Protestants. Such an arrangement would do much good, carried into effect, but nothing had as yet come of it. Prince Charles, now nearly eight, is to be taken out

of the hands of the women and given a little household of his own. The Duchesse de Chevreuse has fled to Madrid, where she has been magnificently entertained. Spain, however, is reported to have become weary of the beautiful intriguante, and a ship has been sent to bring her to England, where she is to be assigned lodgings in the garden at Whitehall. And, lastly in the budget of gossip, Wentworth is informed that Sir Toby Matthews, court flatterer in chief, has written, after the fashion of the day, " characters " both of Lady Carlisle and of the Queen ; whilst another such description of a lady, author unknown, exceeded in wit anything written by Sir Toby, and some credited Lady Carlisle herself with the production—" King, Queen, all have seen it."

So the letter runs on, giving its picture of the petty interests, the daily trivialities, of court life. And that very month the High Treasurer of Scotland, Traquair, had come to London in response to a summons from the King, and was telling Charles that if he wished his Prayer-Book to be read in Scotland he must be prepared to support it by an army of 40,000 men !

In March an event took place imperilling the friendly relations of some of the principal frequenters of the court, whilst it also affords an indication that Holland's influence over Henrietta was suffering diminution. The appointment of Northumberland to be Lord High Admiral had taken most people by surprise, and had caused disappointment to not a few aspirants to the post. The Earl had already rilled the office of Master of the Horse to the Queen, and, as brother to Lady Carlisle and to Henry Percy, had not been lacking in interest to forward his claims. He was also, according to Sir Philip Warwick, " a graceful young man, of great sobriety, regularity, and in all kinds promising and hopeful." Notwith-

standing his qualifications, few except the Queen had been prepared for his advancement ; and Lord Conway, writing to Wentworth, gives an account of the fashion in which one, at least, of his competitors had met his disappointment.

" My Lord of Holland," he wrote, " called a Council —my Lady of Devonshire, my Lady Rich, my Lady Essex, Cheek and Lucas his secretary, to whom he uttered his griefs "—complaining in especial of the secrecy with which the affair had been conducted. " The consult was whether he should bear it patiently, or publish his resentment. The former had been, in my foolish opinion, wisest, and my Lady of Carlisle saith she wonders he did not." Holland, however, had retired to Kensington, on the transparent excuse of health. Moreover, " his tongue, unfaithful to himself—and therefore his friends have the less reason to complain of it—hath so expressed his grief that the Queen makes herself very good sport at it."

With few staunch friends, Holland had many enemies ready to rejoice in his mishaps, and he and Wentworth in especial were foes. " I am told," wrote the Lord Deputy a few months later to the Earl of Newcastle, " my Lord of Holland is very much awakened in the matter "— Wentworth's own concerns—" and verily I forgive him the very worst he can do me in this, or, if it please him, in anything else. . . . Methinks his lordship should desire to clear his hands of it, that at more leisure and freer of thought he might one day write a character, and another day visit Madam Chevreux. He sure were lapped in his mother's smock, which sure enough was of the finest Holland indeed, that hath thus monopolised to himself as his own peculiar the affections and devotions of that whole sex."

The bitter contempt of the man fighting, in spite of

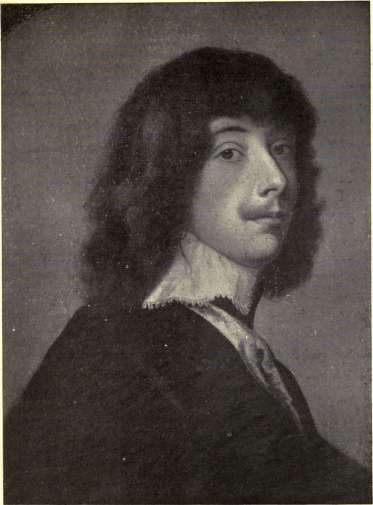

After a copy oj Van Dyck's picture in the National Portrait Gallery.

Photo by Emery Walker.

ALGERNON PERCY, EARL OK NORTHUMBERLAND.

ill-health, calumny and misrepresentation, the King's battle in Ireland, for the courtier engaged in petty intrigues, social and political, is not difficult to understand. The interests by which Wentworth's own life was filled were of a far different type. Nor, granted the fundamental principle of the absolute rights of kings, were his ambitions otherwise than noble. His loyalty was unlimited, his zeal unwearied. He desired to serve first the Crown, then the people ; to assure to the King what he believed to be his own, and to afford protection to the poor and helpless from the tyranny and the exactions of middle men, of the rich and the noble. But to compass his purpose he used any means he might find ready to his hand. He made promises in the King's name, and broke them ; worse, he deliberately contemplated their breach. It would be difficult to summarise the policy he pursued better than has been done by Mr. Gardiner : " The type of his mind was that of the revolutionary idealist, who sweeps aside all institutions which lie in his path, who defies the sluggishness of men and the very forces of human nature in order that he may realise those conceptions which he believes to be for the benefit of all."

Such a man could have no sympathy with the idlers and triflers of a court. With Henrietta he would have had little in common at a time when trouble and care and calamity had not as yet taken effect upon her. But she was ever in his eyes his master's wife, with the glamour of royalty about her ; and when he was compelled to cross her wishes it was done with regretful and reverent courtesy. In a correspondence belonging to this year Henrietta gave proof that she knew how to take a refusal.

" Monsieur Wentworth," she wrote, " I have found

HENRIETTA MARIA

you so prompt to oblige me [on former occasions] that I write to you myself to render you thanks, and also to make you a request in according which you may oblige me more than in anything else ; which is that you would suffer that a devotion that the people of this country have always had to a Place a Saint Patrick, should not be abolished. They will make so modest a use of it that you will have no reason to repent, and you will do me a great pleasure. . . . Your very good friend, H. M. R."

The thing could not be done ; but one is assured that Wentworth felt it hard to refuse a request thus proffered. " The gracious lines I received from your Majesty's own hand," he writes, " concerning St. Patrick's Purgatory, I shall convey over to my posterity as one of the greatest honours of my past life. For the thing itself, it was by act of State decry'd under the Government of the late Lord's Justice before my coming into the Kingdom ; and since I read your Majesty's I can with truth say 1 am glad none of my Counsel was in the matter." Having been abolished, and the spot in question being in the midst of the Scotch plantation, it would be difficult to effect a restoration of the devotion at present. His advice is to let the matter rest awhile, until opportunity should offer of carrying out the Queen's pleasure with regard to it. He is always anxious to serve her.