The life of Queen Henrietta Maria (12 page)

Read The life of Queen Henrietta Maria Online

Authors: Ida A. (Ida Ashworth) Taylor

Tags: #Henrietta Maria, Queen, consort of Charles I, King of England, 1609-1669

only to the Queen, who did much check him for that omission."

When it is borne in mind that help was still being despatched from England to the French insurgents, it cannot but be considered a pardonable lack of courtesy on the part of the envoy to decline to drink Charles' health ; and Henrietta's intervention in the character of a peace-maker must have been the rehearsal of a new part.

In February a contemporary letter again shows her in an attitude of conciliation. On this occasion she was acting as sponsor by h^r deputy, the Duchess of Richmond, to the Duke's infant heir, the King assisting in person at the ceremony, clad " in a long soldier's coat all covered with gold lace, and his hair all goffered and frizzled, which he never used before."

If things were going well in the interior of Whitehall, affairs outside were in a worse condition than before. By the spring it had become impossible to resist the popular demand for a Parliament. The methods devised by Charles and his ministers for raising money had proved wholly ineffective, and on March iyth the House met. Its temper was to be inferred from the fact that no single candidate who had suffered imprisonment owing to resistance to the forced loan exacted by Charles, had failed to win a seat. Opposition to the court had become the high road to popularity.

One of the members thus returned was Sir Thomas Wentworth, the future Earl of Strafford, destined to occupy later on, so far as it was ever filled, the place at present held by the Duke in Charles' confidence. Persistently excluded by Buckingham from the position at court which his brilliant gifts and personal charm might have obtained for him, his recent line of conduct VOL. i. 7

had caused him to be regarded with suspicion by the King, and he had been included amongst the political leaders debarred from a seat in the last Parliament by their appointment to the office of sheriff. He now took his place in the House as an avowed defender of constitutional rights. " We must vindicate our ancient liberties," he cried, summarising the great work lying before himself and his colleagues ; "we must reinforce the laws made by our ancestors ; we must set such a stamp upon them as no licentious spirit will dare hereafter to invade them." The words were remembered against him later on.

The Petition of Right was the embodiment of the vindication to which the King's future minister pointed the way. When, from the discussion of the general condition of the country and the attacks upon its liberties, the House proceeded to give utterance to the fierce hatred entertained for the man held chiefly responsible for the invasion of the people's rights ; when the Duke had been pointed out by name, amidst the acclamations of those present, as the author of all the miseries of the country, Charles, hitherto obdurate or evasive, gave way. He assented to the Petition of Right.

The concession came too late. The Commons refused to cancel the Remonstrance they had prepared, censure of the minister being explicitly included in it. But Charles was as unyielding as they. With the Duke himself standing at his side, he received the deputation come to present the Remonstrance, his demeanour on the occasion indicating his attitude towards the man at whom it was aimed. When the King had made cold response to the delegates, the Duke, falling on his knees, craved permission to make answer to his accusers,

" No, George, no," was Charles' reply, as, raising

the culprit, he gave him his hand to kiss. The man he loved was not so much as to offer a defence to his enemies. The Houses were adjoined shortly after this scene, nor did they meet again till the close of the year.

The session, unfortunate in many respects, had witnessed one event supremely important to King and Queen. This was the defection of Wentworth from the popular party. The motives dictating his present course of action, as well as his former adoption of liberal principles, had probably been mixed. " If this man," says Mr. Forster, not unduly biassed in favour of the future minister, c< had any passion as strong as that which from his earliest years impelled him to the service of the King, it was his impatience and scorn of the men about the court who for so many years had shut its doors upon him." Swayed by anger, he had thrown in his lot with the enemies of the favourite, to whom his exclusion was chiefly due. But passion is not principle, nor are the acts it dictates always a true index to character. " It was the true Wentworth who remained after this had cleared away—not the associate and fellow-patriot of Eliot, but the minister of Charles." His conduct might be devious ; his nature was sincere. His final election was now made. On July 22nd he became a peer, under the title of Lord Wentworth, and was thenceforward a steady supporter of the Crown. 1

1 The account given in J. R. Green's Short History of the transfer of Wentworth's service is a different one. " The death of Buckingham," he says (page 504), " had no sooner removed the obstacle that stood between his ambition and the end at which it had aimed throughout, than the cloak of patriotism was flung by." But it is fair to remember that, whilst the Duke doubtless stood in the way of the attainment of full power on Wentworth's part, the peerage, representing the earnest of court favour and indicating that he was already pledged to support the King, was conferred in July, and that Buckingham's murder did not take place till August.

It needed all the support which could be obtained. On June 26th Parliament had been prorogued, to reassemble, according to the present arrangements, in October. Charles and his minister were meanwhile face to face with a situation of overwhelming difficulty. Rochelle, encouraged to fresh resistance the previous year by the promise of English help, still held out, reduced to the utmost straits of misery and starvation. Should it be left to its fate, Buckingham was convicted of something perilously near to treachery. Should he, on the other hand, prosecute the war with France by going to its assistance, not only was success problematical, but, supposing it was achieved, the Huguenot interests throughout France might be rather injured than promoted. It would, at the same time, put out of the question any hope of French co-operation in the wider struggle with the great Catholic forces of Europe. But in spite of all that could be urged against it, the Duke had decided in favour of a fresh attempt to relieve the beleaguered city. In the anxiety, inconsistent as it was, he professed for peace with France, he was probably sincere. His past dogged him. He found himself committed in honour to a policy impossible to carry out with success. It was not he, however, who was fated to grapple with the difficulties he had created.

At Portsmouth the blow was struck by which he was removed from his place at the helm. The King himself, from a house in the neighbourhood of the seaport, had been superintending the preparation of the fleet to be led by the Duke to the relief of Rochelle. Even at this late stage fresh pressure had been brought to bear upon Buckingham by the Venetian ambassador to induce him to make peace with France. Soubise, the Huguenot leader, was, on the other hand, entreating him to turn a deaf

ear to these counsels. It was unlikely that, at the eleventh hour, they would prevail. But the Duke was not to determine the question.

Forebodings of evil seem to have hung alike over himself and over those who loved him. He had asked Laud to remind the King—who afterwards gave proof that no reminder was needed—of his wife and children. " Some adventure," he observed, " might kill me as well as another man." Yet he rejected the suggestion that, in consideration of his unpopularity, he should wear mail beneath his clothes. " There are no Roman spirits left," he said with a scoff. He was mistaken. As Henri of Navarre had met his death at the hands of a religious fanatic, Buckingham was to fall by the knife of a political zealot.

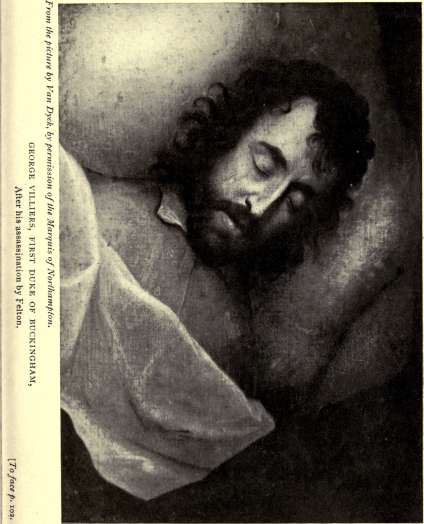

" That man is cowardly base, and deserveth not the name of a gentleman or soldier, that is not willing to sacrifice his life for the honour of God, his King, and his country ... If God had not taken our hearts for our sins, he would not have gone so long unpunished." Thus ran a paper afterwards found upon John Felton. He made good his language by his deed, and stabbed the Duke to the heart.

The King was at prayers with his household when the news was whispered into his ear. As he knelt on, his head bent, his face covered, he gave no sign of grief or disturbance, maintaining his attitude, silent and motionless, till the devotions were concluded. With the same unmoved calm he rose and went to his private chamber. But having reached it, he flung himself on the bed in a passion of tears.

Those who had watched him as he received the fatal intelligence formed their own shallow conclusions from his demeanour. The very greatness of the blow may

have nerved him to bear it with the dignity in which he was rarely wanting. But such was not the interpretation placed upon his composure by men incapable of comprehending his self-restraint. Construing it as indifference, the courtiers, so Clarendon tells us, allowed themselves to fall into the error of speaking with licence of the dead, setting themselves to the dissection of his infirmities, " in which they took very ill measures, for from that time almost till the time of his own death, the King admitted very few into any degree of trust who had ever discovered themselves to be enemies to the Duke."

The same event produces contrary effects. Charles, though in silence, mourned for his friend as David for Jonathan. The neglected wife of the Duke was brokenhearted. Some friends and associates, no doubt, were genuine in their regret ; but the nation as a whole rejoiced as those who rejoice that their enemy is dead. " God bless thee, little David," cried a woman when Felton was led through London ; and the sailors leaving for Rochelle shouted out their last request to the King, that he would deal mercifully with the man who had slain the leader of the expedition.

For the feelings of the Queen it is necessary to have recourse chiefly to conjecture. A French writer asserts —on what grounds he omits to state—that she did not affect a grief she could not feel. But Sir Dudley Carleton, by this time Viscount Dorchester and Secretary of State, writing to Lord Carlisle from Portsmouth at the end of August, says that the " apprehension that sweet Princess showed and still continueth of the fatal blow given here, and ^the comfort she giveth to those many distressed ladies"—the Duke's wife, mother, and sister—"upon this accident, as it is kindly taken by the King, so it must affect all the world."

It was impossible that Henrietta should not have been aware that a danger, and perhaps the chief one. to her domestic happiness, was removed. Although she might have vindicated, in time, her claim to the first place in Charles' confidence, Buckingham would not have relinquished his supremacy without a struggle, and his mastery had been hitherto too entire not to warrant a doubt as to the issue of a trial of strength. The Duke gone, Henrietta had no rival. But whilst conscious of this, the suddenness and terrible completeness of the tragedy may have made her, generous and impulsive as she was, forget her past wrongs and present deliverance in compassion for his fate. And remembering the love she bore her husband in later years, already having its beginnings, it is difficult to believe that a blow striking him so heavily would leave her untouched. The very clamorous jubilation of the crowd would serve to range her on the side of the mourner who, making no secret of his grief, was yet bearing it u manly and princely."

She could afford to be magnanimous. With Buckingham's death a new era had opened for her. Thenceforth none would venture so much as an attempt to stand between man and wife. From this time till public calamities made shipwreck of the royal fortunes, Henrietta was a happy woman.

Contemporary documents afford occasional glimpses into the interior of the palace. Lord Carlisle was absent on a mission to Turin at the time of the Duke's murder, and the letters constantly despatched to him from court give a vivid picture of the state of things prevailing there during the last months of 1628. He could not wish, his wife wrote in October, more affection and happiness between the King and Queen than he would find on his return. And in the following

month he is informed by another correspondent, Thomas Gary, that the King might be imagined to be once more a wooer, and the Queen gladder to receive his caresses than he to make them. On the previous day her birthday had been celebrated by Charles on horseback, where he took the ring offered and was resolved to grow every day more and more galant. The King, Gary writes some three weeks later, had so wholly made over all his affections to his wife, that there was no danger of any other favourite ; whilst she, for her part, had returned to such a fondness and liking of him and his person as it was of as much comfort to themselves as of joy to their good servants.

It was well that it was so, for Charles stood sorely in need of comfort. The fatal blow dealt in August had, according to Sir George, now Lord, Goring's account, also sent to Carlisle, astonished and benumbed all. Charles himself was observed to be more reserved than ever ; though rather, the writer surmises, in order to keep oiFthe torrent of suitors than from any change in a nature the best and most constant he ever knew. Perplexities and troubles were rife. The only joy was in the happy intelligence which Goring, like others, is eager to report between their blessed sweet master and mistress, " which certainly easeth that swelling brave heart of his in these his days of highest trials." More true love Goring never saw. His Majesty being at Theobalds but for four days, the Queen can take no rest in the same nights, but sighs for his return, till when she delights herself with his shadow at her bedside.