The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (24 page)

Read The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn Online

Authors: Nathaniel Philbrick

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century

Custer’s lust for glory had, Benteen was convinced, put the entire regiment at risk. In his typically brash and impulsive way, Custer had attacked the village without proper preparation and forethought. “From being a participant in the Battle of the Washita,” Benteen wrote, “I formed an opinion that at some day a big portion of his command would be ‘scooped,’ if such faulty measures . . . persisted.”

But as others pointed out, the mobility of an Indian village did not allow for the luxury of reconnaissance. By the time a regiment had scouted out the location and size of the village, the encampment was more than likely beginning to disperse. One of Custer’s biggest tactical defenders later became, somewhat ironically, Lieutenant Edward Godfrey, the very officer who’d asked him about Major Elliott. “[The] attack must be made with celerity and generally without knowledge of the numbers of the opposing force . . . ,” Godfrey wrote, “and successful surprise . . . depend[s] upon luck.” Or as another noted expert in plains warfare asserted, Indians “had to be grabbed.”

But Benteen refused to see it that way. Custer, he maintained, had needlessly left one of their own to die—an inexcusable transgression that the regiment must never forget.

Several weeks after the battle, the cavalrymen returned to the Washita. When Custer and Sheridan rode into Black Kettle’s village, a vast cloud of crows leapt up cawing from the scorched earth. A wolf loped away to a nearby hill, where it sat down on its haunches and watched intently as they inspected the site. About two miles away, amid a patch of tall grass, they found Elliott and his men—“sixteen naked corpses,” a newspaper correspondent wrote, “frozen as solidly as stone.” The bodies had been so horribly mutilated that it was at first impossible to determine which one was Elliott’s.

Soon after, Benteen wrote the letter that was subsequently published in a St. Louis newspaper. “Who can describe the feeling of that brave band,” he wrote, “as with anxious beating hearts, they strained their yearning eyes in the direction whence help should come? What must have been the despair that, when all hopes of succor died out, nerved their stout arms to do and die?”

If Custer had committed one certain crime at the Washita, it involved not Major Elliott but the fifty or so Cheyenne captives who accompanied the regiment during the long march back to the base camp. According to Ben Clark, “many of the squaws captured at the Washita were used by the officers.” Clark claimed that the scout known as Romero (jokingly referred to as Romeo by Custer) acted as the regiment’s pimp. “Romero would send squaws around to the officers’ tents every night,” he said, adding that “Custer picked out a fine looking one [named Monahsetah] and had her in his tent every night.” Benteen corroborated Clark’s story, relating how the regiment’s surgeon reported seeing Custer not only “sleeping with that Indian girl all winter long, but . . . many times in the very act of copulating with her!”

There was a saying among the soldiers of the western frontier, a saying Custer and his officers could heartily endorse: “Indian women rape easy.”

S

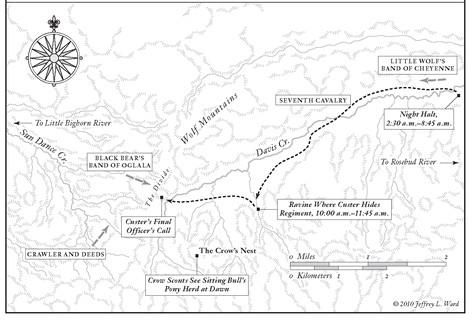

ometime between 2:30 and 3:00 a.m. on the morning of Sunday, June 25, 1876, Lieutenant Varnum awoke on the divide between the Rosebud and Little Bighorn rivers. He was lying in what he described as a “peculiar hollow” nestled under a high peak. The topography reminded him of a similarly shaped mountaintop back at West Point known as the Crow’s Nest, named for the lookout on the masthead of a ship. The Crow’s Nest at West Point provided a spectacular view of the Hudson River valley. What became known as the Crow’s Nest in the Wolf Mountains offered a very different vantage point of the Little Bighorn Valley, about fifteen miles to the west.

Varnum sat beside several Crow scouts as the thin clear light of a new dawn filled the rolling green valley of the Little Bighorn. At West Point, you peered down like God from a great, vertiginous height. Here in the Wolf Mountains, there was no sense of omniscience. As the Crows had warned the Arikara during a smoke break that night, “all the hills would seem to go down flat.”

And that is exactly what Varnum saw in the early-morning hours of June 25: an empty green valley seemingly drained of contour. But the Indian scouts saw much more. “The Crows said there was a big village . . . ,” Varnum remembered, “behind a line of bluffs and pointed to a large pony herd.” But Varnum couldn’t see it, even after looking through one of the Crows’ spyglasses. “My eyes were somewhat inflamed from loss of sleep and hard riding in dust and hot sun,” he later explained. But, as the Crows understood, seeing is as much about knowing what to look for as it is good vision.

Speaking through the interpreter Mitch Boyer, they urged him to look for “worms on the grass”—that was what the herds looked like. But try as he might, Varnum saw nothing. He’d have to take their word for it.

Perfectly visible to all of them were the columns of smoke rising from the eastern side of the divide behind them. The regiment must be encamped and making breakfast. The Crow scouts were outraged. To allow fires of any kind when so close to the enemy was inconceivable. Were the soldiers consciously attempting to alert the Sioux to their presence?

Around 5 a.m. Varnum sent two of the Arikara, Red Star and Bull, back to Custer with a written message. The Crows, he reported, had seen “a tremendous village on the Little Bighorn.”

C

uster had halted the column just before daylight. It had been a brief but punishing march, and many of the men simply collapsed on the ground in exhaustion, their horses’ reins still looped in their hands. Others made themselves breakfast, lighting fires of sagebrush and buffalo chips (which burned blue and scentless) to heat their coffee. Benteen joined Reno and Lieutenant Benny Hodgson, the diminutive son of a Philadelphia whale oil merchant whose wry wit made him one of the favorites of the regiment, in consuming a meal of “hardtack and trimmings.” For his part, Custer climbed under a bush and, with his hat pulled over his eyes, fell asleep—apparently too tired to worry about concealing the regiment from the enemy.

The officers and men were exhausted, but it was the horses and mules who were truly suffering. Under normal conditions, a cavalry horse was fed fourteen pounds of hay and twelve pounds of grain per day. To save on weight, each soldier had been given just twelve pounds of grain for the entire scout, which he kept in a twenty-inch-long sack, known as a carbine socket, strapped to the back of his saddle. Since the Lakota pony herds had virtually stripped the Rosebud Valley of grass, this meant that each trooper’s horse had been living on only two to three pounds of grain per day. Walking among the horses that morning, Private Peter Thompson noticed “how poor and gaunt they were becoming.”

Varnum had given his written message to Red Star, and as the Arikara scout approached the campsite he “began,” he remembered, “turning his horse zig-zag back and forth as a sign that he had found the enemy.” He was met by Stabbed, the elder of the Arikara, who said, “My son, this is no small thing you have done.” Once he’d unsaddled his horse and was given a cup of coffee, Red Star was joined by Custer, Custer’s brother Tom, Bloody Knife, and the interpreter Fred Gerard.

Red Star was squatting with his coffee cup in hand when Custer knelt down on his left knee and asked in sign language if he’d seen the Lakota. He had, he responded, then handed Custer the note. After reading it aloud, Custer nodded and turned to Bloody Knife. Motioning toward Tom, he signed to the Arikara scout, “[My] brother there is frightened, his heart flutters with fear, his eyes are rolling from fright at this news of the Sioux. When we have beaten the Sioux he will then be a man.”

To speak of fear in regard to Tom was, Custer knew perfectly well, an absurdity. Just as the Indians valued counting coup as the ultimate test of bravery, a soldier in the Civil War had wanted nothing more than to capture the enemy’s flag. In the space of three days, Tom went to extraordinary lengths to capture two Confederate flags. The taking of the first, at Namozine Church on April 3, 1865, was spectacular enough to win him the Medal of Honor, but it was the second, taken at Sayler’s Creek, that almost got him killed.

Tom had just spearheaded a charge that had broken the Confederate line. Up ahead was the color-bearer. Just as Tom seized the flag, the rebel soldier took up his pistol and fired point-blank into Tom’s face. The bullet tore through his cheek and exited behind his ear and knocked him backward on his horse. His ripped and powder-blackened face spouting blood, Tom somehow managed to pull himself upright, draw his own pistol, and shoot the color-bearer dead. With flag in hand, he rode back to his brother and crowed, “The damn rebels have shot me, but I’ve got the flag!” Understandably fearful for Tom’s life, Custer ordered him to report to a surgeon, but Tom refused to leave the field until the battle was won. He’d handed the flag to another soldier and was heading back out when Custer placed him under arrest. Soon after, Tom, all of twenty years old, became the only soldier in the Civil War to win two Medals of Honor.

In his derisive remarks to Bloody Knife, Custer was picking up where he and the Arikara scout had left off three days before. The first night after leaving the

Far West,

a drunken Bloody Knife had tauntingly claimed that if Custer did happen to find the Indians “he would not dare to attack.” Custer was now using the supposed fears of his brother Tom as a way to show Bloody Knife that he had no qualms about attacking even a “tremendous village.”

What Custer apparently didn’t fully appreciate was the extent to which the ever-growing size of the Indian trail had already changed his scout’s attitude toward what lay ahead. The evening before, during their last encampment on the Rosebud, Bloody Knife had said to a small group of fellow scouts, “Well, tomorrow we are going to have a big fight, a losing fight. Myself, I know what is to happen to me. . . . I am not to see the set of tomorrow’s sun.”

That morning on the eastern slope of the Wolf Mountains, Custer leapt onto his horse Dandy and rode bareback throughout the column, spreading the news of the Crows’ discovery and ordering each troop commander to prepare to march at 8 a.m. There was at least one officer to whom he did not speak. “I noticed Custer passed me on horseback,” Benteen wrote. “[He] went on, saying nothing to me.”

By the time Custer returned to his bivouac, he was in a more meditative mood. When Godfrey approached him just prior to their 8 a.m. departure, Custer “wore a serious expression and was apparently abstracted” as a nearby group of Arikara, including Bloody Knife, discussed the prospects for the day ahead. At one point Bloody Knife made a remark that caused Custer to look up and ask, “in his usual quick, brusque manner, ‘What’s that he says!’ ”

“He says,” Gerard responded, “we’ll find enough Sioux to keep us fighting two or three days.”

Custer laughed humorlessly. “I guess we’ll get through with them in one day,” he said.

A

t 8:00 sharp, Custer led the column due west on a gradual climb toward the divide. At 10:30, after a march of about four miles, he directed the regiment toward a narrow ravine less than two miles east of the divide. As Custer, Red Star, and Gerard continued on to the Crow’s Nest, the soldiers were to hide themselves here until nightfall.

The officers and men climbed down into the cool depths of this subterranean pocket of sagebrush, buffalo grass, and brush. After three days and a night of marching, it was a great relief to be free, if only temporarily, from the dust and sun. Several officers, including Godfrey, Tom Custer, Custer’s aide-de-camp Lieutenant Cooke, Lieutenant Jim Calhoun, and Lieutenant Winfield Scott Edgerly smoked companion-ably in the ravine. They now knew that the day of the fight was finally at hand. Edgerly, the youngest of the group, later remembered how Cooke laughed and, speaking figuratively, predicted, “I would have a chance to bathe my maiden saber that day.”

O

n the other side of the divide, climbing up into the Wolf Mountains from the west, were two groups of Lakota. The first comprised just two people, Crawler, the camp crier for the prestigious warrior society known as the Silent Eaters (of which Sitting Bull was the leader), and Crawler’s ten-year-old son, Deeds. The previous day Deeds had been forced to abandon his exhausted horse in the vicinity of Sun Dance Creek, a small tributary of the Little Bighorn that flows west from the divide. Deeds had doubled up on his brother’s horse and ridden back to the village on the Little Bighorn. Early that morning, he and his father headed out to find the horse.

They were now about a mile to the west of the divide, riding toward the gap where the Indian trail passed over the crest of the Wolf Mountains. Crawler was in front, holding a long lariat that led to the newly recaptured pony, with Deeds just a little behind. It was a beautiful summer morning, not a cloud in the sky, as they rode up the grassy mountainside. At some point Crawler noticed a cloud of dust rising from the other side of the divide. A group of people was approaching from the east. Even though a great battle had been fought the week before, he didn’t assume these were soldiers. As the Lakota had long since learned, not all the washichus who wandered the plains wanted to fight.

—THE MARCH TO THE DIVIDE,

June 25, 1876

—