The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (5 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Both Macdonald and his minister of railways, Sir Charles Tupper, were a little wary of Macoun, and not without reason. He was a man with a fixed idea, which had come close to being an obsession. The evidence suggests that he was prejudiced in advance. Long before he actually visited the southern prairie he was making pronouncements about its riches. After he did see it, he tried to show that its fertility was even greater than that of the land to the north. So passionate an advocate was he that he once leaped up from the Visitors’ Gallery of the House of Commons to berate Alexander Mackenzie, in opposition, for attacking the Government on the question of prairie soil. Mackenzie had Macoun’s enthusiastic report of 1877 in his desk, and Macoun, at the risk of being ejected, was trying to get him to quote from it. Macoun did not visit the southern prairie, however, until 1879. Then he “fearlessly announced that the so-called arid country was one of unsurpassed fertility, and that it was literally the ‘Garden of the whole country’.…”

How could one explorer have seen the plains as a lush paradise while another saw them as a desert? How was it that Macoun found thick grasses and sedges where Palliser reported cracked, dry ground? The answer lies

in the unpredictability of the weather in what came to be called Palliser’s Triangle. Frank Oliver, the pioneer Edmonton editor, once remarked that anyone who tried to forecast Alberta weather was either a newcomer or a fool. Palliser saw the land under normal to dry conditions; Macoun visited it during the wettest decade in more than a century. If the former was too pessimistic, the latter was too enthusiastic.

Macoun was brought to St. Paul to convince the

CPR’S

executive committee (only Duncan McIntyre, the vice-president, was absent) that a more southerly route to the Rockies was practicable. Hill and the others were already partially convinced. Early in November, 1880, Angus wrote to Winnipeg inquiring about the possibilities of a more southerly route. His contact was that curious diplomatic jack-of-all-trades, the amiable American consul James Wiekes Taylor, who had once been an agent for the Northern Pacific when that railway had hoped to seize control of the Canadian North West. Taylor, long an enthusiast about the southern prairies, had originally fired the botanist’s imagination on the subject when Macoun visited Winnipeg with Sandford Fleming in 1872. At that time Taylor told Macoun that the area would become the wheat-producing country of the American continent. In his correspondence with Angus in 1880, Taylor (who was doing his best to get a retainer from the

CPR)

showed that his enthusiasm had not waned. He cited several Hudson’s Bay Company reports to back up his belief that a southern route was feasible and he quoted John Macoun, who had told the press that “the roses were in such profusion that they scented the atmosphere” and that water could be found in any part of the Palliser Triangle by sinking shallow wells. Taylor had also talked to Walter Moberly, the surveyor who had long been a trenchant champion of a more southerly route through British Columbia; in his correspondence with Angus he made light of the problem of the three mountain ranges that barred the way to the Pacific.

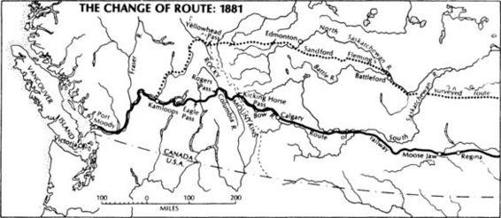

Immediately the new company was formed, in February, 1881, Jim Hill hired an American railway surveyor, Major A. B. Rogers, and sent him off to the Rocky Mountains, which Rogers had never seen, with orders to examine the four most southerly passes, three of which – the Kicking Horse, Vermilion, and Kootenay – had been ignored by the government’s survey teams. The fourth, Howse Pass (Walter Moberly’s favourite), had been rejected by Sandford Fleming after a cursory examination. Rogers, a profane, tobacco-chewing, irritable Yankee, arrived in Kamloops late in April, prepared to start work. His presence raised the hackles of more than one Canadian nationalist. “We are not inclined to credit the Yankee employees of the Syndicate with all the prodigious engineering feats that

they promised to perform,” the Toronto

Globe

editorialized with some asperity on May 3. After all, the Canadians had spent ten years examining no fewer than seven passes in the Rockies before settling on the Yellow Head. Who were these American to suggest they were wrong?

But Hill and his colleagues were already leaning strongly towards a more southerly route. The only stumbling block was the historical belief that the land it would pass through was semi-desert. All they needed was Macoun to convince them that Palliser and Hind were wrong. It did not take the voluble naturalist long to effect their conversion. After he was finished, a brief discussion followed. Then Hill, according to Macoun’s own account, raised both his hands and slammed them down on the table.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “we will cross the prairie and go by the Bow Pass, [Kicking Horse] if we can get that way.” With that statement, ten years of work was abandoned and the immediate future of the North West altered.

Why were they all so eager to push their railroad through unknown country? Why did they give up Fleming’s careful location in favour of a hazardous route across two mountain ramparts whose passes had not yet been surveyed or even explored? If the Kicking Horse were chosen it would mean that every pound of freight carried across the mountains would have to be hoisted an additional sixteen hundred feet higher into the clouds. Even more disturbing was the appalling barrier of the Selkirk Mountains, which lay beyond the Rockies. No pass of any description had yet been found in that great island of ancient rock; the general opinion was that none existed. Yet the company was apparently prepared to drive steel straight through the Rockies and right to the foot of the Selkirks in the sublime hope that an undiscovered passage would miraculously appear.

The mystery of the change of route has never been convincingly unravelled.

A variety of theories has been advanced, some of them conflicting. Even the

CPR’S

own records do not provide any additional clues as to the real or overriding reasons for the decision that was made in May of 1881.

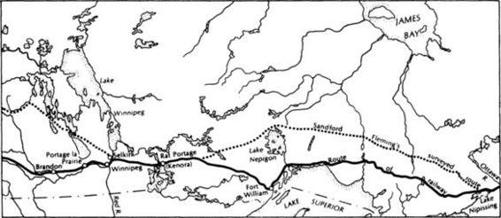

The chief reason given by Sir Charles Tupper in Parliament a year later was that it would shorten the line by seventy-nine miles and give it a greater advantage over its American rivals. Certainly this would have appealed to Jim Hill, with his knowledge of transportation, and to George Stephen, whose mind moved in logical lines, straight from point A to point B. Yet if no pass in the Selkirks could be found, then the railway would have to circumvent those mountains by way of the hairpin-shaped Columbia Valley and almost all the advantage over the northern route would be lost. Moreover, as Edward Blake, the Opposition leader, pointed out, the company in changing the line of route along Lake Superior had actually lengthened that section of the railway.

It is unlikely that the shortening of the line was the chief reason for adopting a new route. Subsequent accounts have generally attributed the move to fear of competition from American lines, which could send feeders into the soft underbelly of the country if the Canadian Pacific trunk-line ran too far north. Some historians, indeed, have suggested that the change of route was inspired by the government for nationalistic reasons. This is scarcely tenable, since it was the government that had authorized and surveyed the northern route at great expense. It was the company and not the government that pressed for the change, and the government, in the person of John Henry Pope, Macdonald’s minister of agriculture, that seemed reluctant about the change. “They are trying the Howe

[sic]

Pass,” he wrote to the Prime Minister on August 19, “… but I do not see how

we can accept that line as the charter says they must go by the other pass.… It seems to me without further legislation we cannot addopt How pass for maine line.” The

CPR

might, in fact, have gone even farther south had the government allowed it; but the change was permitted only on condition that the railroad be located at least one hundred miles north of the border.

Stephen, certainly, was concerned about American encroachment in the shape of the Northern Pacific, a company that had been trying for more than a decade, under various managements, to seize control of the Canadian North West. It had reached no farther than North Dakota by 1881, but its new president, the brilliant if erratic journalist and financier Henry Villard, had already succeeded in buying control of a local Manitoba line, the Southwestern. Villard was planning to cross the Manitoba border at three points. If he did he would certainly siphon off much of the Canadian through trade and make the

CPR

line north of Lake Superior practically worthless.

On the other hand, Stephen had the controversial “Monopoly Clause” in the

CPR

contract to protect him. Under its provisions no competing federally chartered Canadian line could come within fifteen miles of the border; Macdonald was prepared to disallow provincial charters for similarly competing lines. No doubt Stephen felt that the more southerly route provided him with extra insurance against the Northern Pacific and against other United States railways (not to mention rival Canadian roads that might be built south of the

CPR

) when, in twenty years time, the Monopoly Clause would run out. Undoubtedly, this was a consideration in adopting the new route.

Was this the chief consideration? Perhaps. The hindsight of history has made it appear so. Yet Hill himself was already dreaming dreams of a transcontinental line of his own, springing out of the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba road. Stephen and the other major

CPR

stockholders all had a substantial interest in that American railway. If the frustration of United States competition was the reason for the decision of 1881, why was Hill the man who made the decision to move the route south?

Hill did give his reason for changing the route when he banged on the table and made the decision. Macoun, in his autobiography, quoted it:

“I am engaged in the forwarding business and I find that there is money in it for all those who realize its value. If we build this road across the prairie, we will carry every pound of supplies that the settlers want and we will carry every pound of produce that the settlers wish to sell, so that we will have freight both ways.”

This was Hill’s basic railroad philosophy – a philosophy he had ex

pounded over and over again to Stephen in the days of the St. Paul adventure: a railroad through virgin territory creates its own business. It was for this reason that Hill was able to convince Stephen that the

CPR

should not attempt to make a large profit out of land sales but should, instead, try to attract as many settlers as possible to provide business for the railway. The philosophy, of course, would have applied to a considerable extent to the original Fleming line. On the other hand, that line ran through country where some settlement already existed and where real estate speculators – at Battleford and Prince Albert, for example – expected to make profits out of land adjacent to the right of way. It undoubtedly occurred to the railway company that it would be easier to control an area that had never known a settler and where there were no established business interests of any kind. Why should the road increase the value of other men’s property? Why should the

CPR

become involved in internecine warfare between rival settlements? The unholy row between Selkirk and Winnipeg was still fresh in the minds of both Hill and Stephen. Winnipeg businessmen had forced a change in the original survey to bring the main line through their community. In striking comparison was the

CPR’S

founding of the town of Brandon that spring of 1881. The company arbitrarily determined its location in the interests of real estate profit, and the company totally controlled it.

That was to be the pattern of future settlement along the line. In the case of Regina, Calgary, Revelstoke, and Vancouver, to mention the most spectacular instances, it was the company that dictated both the shape and the location of the cities of the new Canada – and woe to any speculator who tried to push the company around! The company could, and did, change the centre of gravity by the simple act of shifting the location of the railway station. For it was around the nucleus of the station that the towns and villages sprang up. The contract stipulated that if government land was available it would be provided free for the company’s stations., station grounds, workshops, dock grounds, buildings, yards, “and other appurtenances.” With a scratch of the pen the company could, and did, decide which communities would grow and which would stagnate; the placing of divisional points made all the difference. “It must not be forgotten,” the

Globe

reminded its readers in 1882, “that the Syndicate has a say in the existence of almost every town or prospective town in the North-West. Individuals rarely have an opportunity of starting a town without their consent and co-operation.” Since some eight hundred villages, towns, and cities were eventually fostered in the three prairie provinces by the

CPR

, the advantages of total control were inestimable.