The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (40 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Normally, one took a ship to New Westminster, transferred to a river boat, and transferred again to a smaller steamboat at Harrison. But when Hagan made the trip, the water in the Fraser was so low and full of ice that the passengers were forced to walk from Harrison River three miles to the head of steel at Farr’s Bluff, where they boarded the train.

An engine had backed down with a tender full of wood, pulling an open flat car normally used for carrying ballast for the roadbed, with the usual iron rail down the centre to keep the gravel plough in place. It was an unprepossessing conveyance encased in a rime of dirt, snow, and ice. The passengers piled aboard by the light of the conductor’s lantern. Most had fur coats, “but not so ye editor who left home in good weather and depended upon his waterproof.”

The night was cold and stormy. The train, which had jumped the track four times en route, crept hesitantly east. “Passing around Seabird Bluff, where the storm had a sweep at the unfortunates, Dana’s narrative of going round Cape Horn was uppermost in our minds.” Finally, a snowdrift blocking the right of way brought the train to a stop.

The passengers helped to get it moving again. As they entered the first tunnel above Hope, huge icicles were sheared from the roof by the locomotive, the glass on the cab was smashed, the fireman cut about the face and head, and one passenger injured when a jagged chunk of ice crushed his leg.

There was a second delay above Emory when the train ploughed into another snowbank, came to a halt on the very lip of the canyon, backed away, and gathered steam to make a rush at the blockade. “As one gazed to the left and beheld the steep embankment, with boulders below, and, looking up the right, hanging trees and threatening rocks were not pleasant to behold while the storm raged. But the ‘sensation’ was experienced when with increased speed the engineer was trying to get good headway to get through the snowdrift and a wheel got off the track and jumped and jarred over half a dozen ties before the track was again taken. In an instant the

conductor sprang to his feet and a few of the passengers were agitated. Not a word was uttered by any person; our stretched along position caused us to feel the shock acutely and our hand grasped as if by instinct the iron rail placed upon the centre of the car. Finally the passengers reached Yale at 1 o’clock in the morning, cold, tired, but hopeful that they will never experience another such ride.”

After the town burned down for the second time, it began to take on a more sober and less flamboyant appearance. Concerts, recitals, lectures, and minstrel shows (with “comic Chinese skits” as well as the mandatory “comic Negro skits”) began to vie with the saloons for patronage. An entertainment institute was formed, for whose first recital Mrs. Onderdonk kindly lent her piano. “Applause was liberally indulged in and enthusiastic encores followed some of the pieces.… Prof. Pichelo, the violinist, especially, met with marked approval.” The Chinese opened their own Freemason’s Lodge with an ornamental flagstaff, as well as a joss-house – institutions which, in the

Sentinel’s

rosy phraseology, demonstrated “that our Chinese population have faith in the future of Yale.” Grand balls were held, in which people danced all night – and even longer – to the music of scraping violins. “A ball out here means business,” wrote Dr. Daniel Parker, Charles Tupper’s travelling companion. “The last one … commenced at 12 o’clock on Monday morning and lasted continuously day and night until 12 o’clock the next Saturday.”

On the great fête-days the community, bound by a growing feeling of cohesion, turned out en masse. The Queen’s Birthday on May 24 was an occasion for a half-holiday for whites and Indians. Chinese New Year, celebrated by the coolies early in February, ran for an entire week and “favourably impressed the white people of Yale.” The biggest event of all was the Fourth of July, since Yale was very much an American town; indeed, Hagan declared in his newspaper that the large number of Americans working on the railway “have caused the B. Columbians to worry about the possibility of the Americans forcing the province into American hands.”

Nonetheless, everyone turned out to honour the day that, again in Hagan’s words, “gave birth to free America – the home of the oppressed of all nations.” Half the population of New Westminster chugged up the river for the occasion on the

William Irving

, decked with greenery and flying pennants, a band playing on her upper deck. Cannons roared. Locomotives pulled flat cars crammed with excursionists from neighbouring Emory. Indians climbed greased poles. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was enthusiastically rendered outside of the Onderdonk home. Couples tripped

“the light fantastic toe,” in the phrase of the day, on a special platform erected on the main street. There were horse races, canoe races, caber-tossing, and hurdles. “It was conceded on all hands that the day was a gala one.…” By comparison, July 1, celebrating a Confederation that was less than a generation old, passed almost unnoticed. British Columbia was part British and part American; it would require the completion of the railway to make her part of the new dominion.

Far off beyond the mountains – beyond the rounded bulks of the Gold Range, beyond the pointed peaks of the mysterious Selkirks – the rails were inching west; but as far as Onderdonk’s navvies were concerned, that land was almost as distant as China. “… we really knew very little about what they were doing on that side,” Henry Cambie recalled. Any letters, if such had been written, would have had to travel down the muddy Fraser by boat, on to Victoria and thence to San Francisco, across the United States to St. Paul, north into Winnipeg, and then west again until they reached End of Track. The distance involved was more than five thousand miles, and yet, in 1883, End of Track was only a few hundred miles away.

Chapter Six

1

The Promised Land

2

The displaced people

3

Prohibition

4

The magical influence

5

George Stephen’s disastrous gamble

6

The CPR goes political

1

The Promised Land

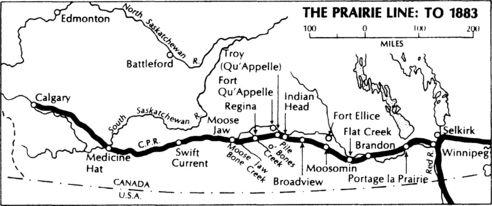

By the spring of 1883, Canada was a country with half a transcontinental railroad. Between Port Moody and Ottawa, the track lay in pieces like a child’s train set – long stretches of finished road separated by formidable gaps. The easiest part of the

CPR

was complete: a continuous line of steel ran west for 937 miles from Fort William at the head of Lake Superior to the tent community of Swift Current in the heart of Palliser’s Triangle. To the west, between Swift Current and the half-completed Onderdonk section in British Columbia, was a gap of 750 miles on parts of which not even a surveyor had set foot. The section closest to civilization was graded, waiting for the rails to be laid. The remainder was a mélange of tote roads, forest slashings, skeletons of bridges, and engineers’ stakes. An equally awesome gap, of more than six hundred miles, extended east from End of Track near Fort William to the terminus of the newly completed Canada Central Railway on Lake Nipissing. Again, this was little more than a network of mired roads chopped out of the stunted timber and, here and there, some partially blasted tunnels and rock cuts.

By the time the snows melted almost the entire right of way for twenty-five hundred miles, from the rim of the Shield to tidewater, was abuzz with human activity. In the East, the timber cutters and rock men who had endured the desolation of Superior’s shore the previous winter were ripping a right of way out of the Precambrian wilderness. In the Far West, more thousands were invading the land of the Blackfoot tribes and clambering up the mountains. Little steel shoots were sprouting south, west, and east of the main trunk-line in Manitoba. And wherever the steel went, the settlers followed with their tents and their tools, their cattle and their kittens, their furniture and their fences.

From the famine-ridden bog country of Ireland, the bleak crofts of the Scottish hills, and the smoky hives of industrial England, the immigrants were pouring in. They clogged the docks at Liverpool – three thousand in a single record day, half of them bound for Manitoba – kerchiefed women with squalling infants, nervous young husbands, chalky with the pallor of the cities, and the occasional grandmother, all clutching in a last embrace those friends and relatives whom they never expected to see again. They endured the nausea of the long sea journey, emerged from the dank holds of Sir Hugh Allan’s steamships at Halifax and Montreal, and swarmed aboard the flimsy immigrant cars that chugged off to the North West – the “land of milk and honey,” as the posters proclaimed it. Occasionally some sardonic newcomer would scribble the qualification, “if you keep cows and bees,” beneath that confident slogan; but most of the arrivals cheerfully believed it, enduring the kennels of the colonist cars in the sure knowledge that a mecca of sorts awaited them.

The land moved past them like a series of painted scenes on flashcards – a confused impression of station platforms and very little more, because the windows in the wooden cars were too high and too small to afford much of a view of the new world. They sat crowded together on hard seats that ran lengthwise and they cooked their own food on a wood stove placed in the centre of the car. They were patient people, full of hope, blessed by good cheer. In the spring and summer of 1883, some 133,000 of them arrived in Canada. Of that number, two-thirds sped directly to the North West.

No one, apparently, had expected such an onslaught. The demand for Atlantic passage was unprecedented. The

CPR

found it had insufficient rolling stock to handle the invading army and was obliged to use its dwindling reserves of cash to buy additional colonist cars second-hand. In Toronto, the immigrant sheds were overflowing; in May alone ten thousand meals were served there – as many as had been prepared in the entire season of 1882. The young Canadian postal service was overtaxed with twelve thousand letters destined for the North West. The number had quadrupled in just two years.

In Winnipeg, the

Globe

reported, the scene at the station was “as good as a show … it reminds one of exhibition times in Toronto.” The settlers from the Old World – some had come from places as remote as Iceland – had been joined by farmers from the back concessions of Ontario. Hundreds of Winnipeggers poured down to meet friends from the East or to see them off for the new land; “the amount of indiscriminate kissing done in a day would have shocked the Ettrick shepherd.” Already the rough democracy of the frontier was making itself felt. It was “nothing

unusual to see a man who would scorn to carry a small parcel on the street in the east rushing for the train with a tent rolled over his shoulder and a camp stove under his arm. Pioneer life plays havoc with false pride and northwest mud is no respecter of persons.”

Off to the west the trains puffed, every car crammed – some people, indeed, clinging to the steps and all singing the song that became the theme of the pioneers: “One More River to Cross.” The

CPR

by April was able to take them as far as the tent community of Moose Jaw, four hundred miles to the west, and, on occasion, a hundred and fifty miles farther to Swift Current. As many as twenty-five hundred settlers left Winnipeg every week, “not to wander over the prairie as was the case last spring, but to locate on land already picked out for and entered for by themselves or their friends.” Under such conditions it was not always easy to tell blue blood from peasant. The man on the next homestead or the waiter serving in a tent restaurant might be of noble birth; the son of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the poet laureate, was breaking sod on a homestead that spring. Nicholas Flood Davin, the journalist, on his first day in Regina was struck by the gentlemanly bearing of the waiter in the tent where he breakfasted. He turned out to be a nephew of the Duke of Rutland, engaged in managing a hastily erected hotel for the nephew of Earl Granville, who had opened a similar establishment in Brandon.