The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 (29 page)

Read The Last Spike: The Great Railway, 1881-1885 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Guided by the pioneer Methodist missionary John McDougall, who happened upon the surveyors and offered his services, the wagon train moved forward again. The hills became so steep that sixteen horses were needed to move one wagon and forty men to hold it back on the down grades. “Just as soon as the snow begins to fall I am, as sure as Christ, getting out of this God-forsaken country,” one of the men blurted (thereby again breaking a Hyndman commandment). McDougall cannily seized upon the phrase “as sure as Christ” for the sermon he preached that Sunday.

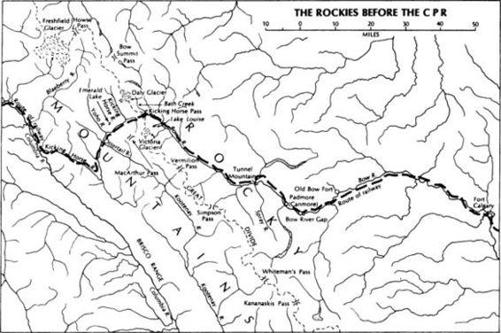

When the Baker Company’s freighters turned back at the end of their contract point, Old Bow Fort, McDougall’s brother Dave, a pioneer trader, moved the freight forward to the Bow River Gap where Hyndman and his men were to rendezvous with their chief. Although the party was several days late, there was no sign of Rogers.

About a week later – the date was July 15 – Tom Wilson was sitting on a narrow Indian trail west of the camp, smoking his pipe, when a mottled roan cayuse appeared around a curve carrying a man wearing an old white helmet and a brown canvas suit. The rider, accompanied by two Shuswap Indians, was more than trail-worn. “His condition – dirty doesn’t begin to describe it,” Wilson remembered. “His voluminous side-burns waved like flags in a breeze; his piercing eyes seemed to look and see through everything at once.… Every few moments a stream of tobacco juice erupted from between his side-burns; I’ll bet there were not many trees alongside the trail that had escaped that deadly tobacco juice aim.”

Wilson realized at once that the tattered creature on the scarecrow horse must be the notorious Major Rogers.

“This Hyndman’s camp?” the Major asked in his jerky manner.

Wilson nodded and guided Rogers to Hyndman’s tent. Hyndman stepped out, but there was no word of greeting from his chief.

“What’s your altitude?” he shot at Hyndman. The engineer stammered that he did not know.

“Blue Jesus!

*

Been here several days and don’t know the altitude yet. You——!” There followed what Wilson described as “a wonderful exhibition of scientific cussing [which] busted wide all of Hyndman’s ‘Holy Commandments’ and inspired delighted snickers and chuckles of admiration from the men who had quickly gathered around.” No further word was heard about either the strike or the commandments.

Rogers told the men that the utmost speed was essential if the survey was to keep up to schedule since the season was late and the work well behind. One party left the following morning for the Kananaskis summit of the Bow; the others worked their way westward, widening the Indian trail as they moved.

Three days later Rogers announced that he intended to set off on his own to do some exploring, but when he asked for a volunteer to accompany him, the request was greeted by absolute silence.

There was good reason for it. As Wilson put it, “every man present had learned, in three days, to hate the Major with real hatred. He had no mercy on horses or men – he had none on himself. The labourers hated him for the way he drove them and the packers for that and the way he abused the horses – never gave their needs a thought.”

In spite of himself Wilson thought he might as well take a chance, and follow Rogers.

“You were the only man who would go with the old geyser,” A. E. Tregent reminded him in a nostalgic letter, forty-eight years later. “Nobody else had the pluck to run the chance of being starved to death or lost in the woods.”

The parties began to peel off from the main force on their various assignments, Rogers and Wilson accompanying one up towards the head of the Bow Valley. The Major was clearly worried about the fate of his nephew, whose task it was to come directly across the mountains by the Kicking Horse and Bow rivers.

“Has that damned little cuss Al got here yet?” was his first question on riding into camp one afternoon after an exploration. It was some time before Wilson came to understand that Rogers’s manner of speaking about his nephew was part of his armour – a shield to conceal his inner distress.

When Rogers learned that there was no sign of Albert, he began to prance around and shout.

“Where has that damn little cuss got to?” he kept asking, over and over again. “If anything happens to that damn little cuss I’ll never show my face in St. Paul again.” He was beside himself. The fact that he had given a 21-year-old youth a task that the Indians themselves would not tackle did not seem to have occurred to him; obviously, he expected the impossible.

Rogers decided to search for his nephew in the mountains south of the Bow, and shortly, he and Wilson turned their horses down the great valley.

It was a searing day in late July – a day in which the melting glaciers had turned the gentle streams to torrents. They reached an unnamed creek pouring out of the ice-field on Mount Daly and found it terribly swollen, the current tearing at top speed around enormous boulders. Wilson knew that all glacial streams begin to rise in the afternoon after the sun melts the ice in the mountains. He suggested they halt for the night and cross over when the water had subsided in the cool of the morning. Rogers swore a blue oath.

“Afraid of it are you? Want the old man to show you how to ford it?”

He spurred his horse, forged into the current, and was immediately caught by the racing stream. The horse rolled over and the Major dis-appeared

beneath the foaming, silt-laden water. Wilson seized a long pole, managed to push it towards the spot where the struggling form had disappeared, was rewarded by an answering tug, and proceeded to pull his bedraggled chief to the safety of the bank. Rogers gave him a funny look.

“Blue Jesus! Light a fire and then get that damned horse. Blue Jesus, it’s cold!”

In such a fashion did Bath Creek get its name. The story was soon all over the mountains. In the flood season, when the creek pours its silty waters into the larger river, the normally pristine Bow is discoloured for miles, and for years when that happened old surveyors would mutter sardonically that the old man was taking another bath.

A further day of searching failed to locate the missing Albert. When Rogers and Wilson returned to the summit, hoping for word of him, there was only silence. The Major grew more and more excitable. He tried to rout the men out to search in the black night, but they sensibly refused. “How the Major put in that night I do not know,” Wilson confessed, “but I do know that at daybreak next morning he was on the warpath cursing about late risers.” The members of the summit party were dispatched in all directions to fire revolvers and light signal fires if the lost should be found. Somewhere down below, on the tangled western slope of the Rockies, wrinkled by canyons and criss-crossed by deadfalls, was the missing man – dead or alive, no one could say.

Down that western slope Tom Wilson and a companion made their way through timber so thick they could not see a yard ahead and over carpets of deceptive mosses, which masked dangerous crevices and deep holes. Finally they reached the mouth of a glacial stream later to be called the Yoho. There they made camp, tentless, cooking their tea, bannock, and sowbelly all in the same tin pail. They had scarcely finished their meal when a shot cracked out in the distance. They sprang to their feet and began clambering down the stream bed, shouting as they went; rounding a curve, they came upon the missing man. Albert Rogers was starving and on the point of mental and physical exhaustion. His rations had long since been used up and for two days he had had nothing to eat but a small porcupine. He had picked it clean, right down to the quills.

The ascent back up the Kicking Horse, which the trio made the following day with Albert Rogers’s two Indians, was so terrible that half a century later Wilson insisted that it could not be described. Nearing the summit, they fired a fusillade of revolver shots and a moment later the little major came tearing down the trail to meet them. He stopped, motionless, squinting intently at his nephew; and then Wilson was permitted, for a

moment, to glimpse the human being concealed behind that callous armour of profanity.

“He plainly choked with emotion, then, as his face hardened again he took an extra-vicious tobacco-juice-shot at the nearest tree and almost snarled … ‘Well, you did get here, did you, you damn little cuss?’ There followed a second juice eruption and then, as he swung on his heel, the Major shot back over his shoulder: ‘You’re alright, are you, you damn little cuss?’ ”

Al Rogers grinned. He understood his uncle. “He also knew that, during the rest of the walk to camp, the furious activity of his uncle’s jaws and the double-speed juice shots aimed at the vegetation indicated our leader’s almost uncontrollable emotions.”

There was an eerie kind of undercurrent drifting about the Rogers camp that evening. As twilight fell, purpling the valleys and making spectres of the glacial summits, the men began to gather around the fire, sucking on their pipes and gazing off across the unknown ocean of mountains. Albert Rogers, still shaky from his ordeal, was present; so was Tom Wilson, together with eighteen others – axemen, chainmen, packers, transit men, and cook. Only the Major, toiling in his tent, was absent.

They were perched on the lip of the Great Divide – the spine of the continent – and they were conscious of both the significance and the loneliness of their situation. The feeling of isolation that descends on men who find themselves dwarfed by nature in an empty land was upon each of them. In all of that vast alpine domain there was scarcely, so far as they knew, another human soul. The country was virtually unexplored; much of it had never known a white man’s moccasins. They themselves had trudged through forests, crossed gorges, and crept up slopes that no man, white or native, had ever seen. What nameless horrors did these peaks and ridges hold? For all they knew (as Wilson was to write), ferocious animals of unknown species or fearful savages of barbaric habit lurked somewhere beneath them in those shrouded hollows. To many it was inconceivable that the mountains would ever be conquered or the chasms bridged.

One declared emphatically that no railroad would ever get through such a God-forsaken land and several grunted agreement. Others argued that the success of the project depended on Rogers’s ability to discover a pass in the Selkirks.

“Wonder where we will all be this time next year,” someone said.

“Not here! No more of this for me!” another responded. He wanted to go where there was decent grub and “not seven days work a week, wet or dry.” A chorus of approval greeted this remark. For weeks they had all

existed on dried salt pork, boiled beans, and tea. They had seen no butter, eggs, vegetables or fruit; and there was no time to hunt for the game that abounded. The monotonous diet and the need to be one’s own bootmaker, tailor, barber, and laundryman was beginning to tell. “Let me get back to the settlements and this damn country won’t see me again,” one man declared.

Again, they discussed the railroad and again, when one of the party remarked that no line of steel could get through the Kicking Horse – that if a railway ever reached the west coast it would be by way of Fort Edmonton and the Yellow Head Pass – a majority of heads nodded in agreement.

There followed a strange and moving scene. The fire crackled. The peaks above stood out like ghostly shadows against the night sky. The men pulled on their pipes and stared into the flames. Nobody spoke for some time. At length, one man broke the silence:

“Let’s make a deal,” he said. “Let’s promise to keep in touch with each other at least once a year after we get out of here.”

The twenty men got to their feet and, without further prompting, took part in a solemn ritual. Each one raised an arm to the sky, and all gravely vowed to keep the Pledge of the Twenty, as it came to be called. In the years that followed, almost all were faithful to it.

*

As a result of Albert Rogers’s ordeal, the Kicking Horse Pass had been explored, after a fashion. The next task was to survey a preliminary line from the summit to the base. Wilson resumed his job as personal attendant to Major Rogers, visiting all the survey parties in the vicinity save for the one working along the Kananaskis. Rogers, who was a creature of whim and hunch, apparently had no faith in that route. He had pinned his hopes on the Kicking Horse, with the Bow Summit as his second choice. In this stubborn espousal of a single route, Rogers resembled most of the other leading railway surveyors. Each had a fixed idea in his mind from which he could not be budged. In a remarkable number of cases, they fell in love with the country they first explored. With Walter Moberly, it was the Howse Pass; with Sandford Fleming, the Yellow Head; with Charles

Horetzky, the Pine Pass; with Marcus Smith, Bute Inlet. Each of these unyielding and temperamental men jealously embraced the cause of a piece of real estate almost as if he were married to it.

On their last joint trip of the year, Rogers and Wilson all but came to blows. They had been travelling all day; the horses were worn out; Rogers had refused to halt for lunch; and Wilson was hungry, tired, and boiling mad. Since the indefatigable Major gave no sign that he intended to make camp, Wilson took matters into his own hands, bringing the packhorses to a stop in a small meadow where there was plenty of feed. Rogers continued stubbornly on and soon disappeared into the trees. Wilson attended to the animals, pitched the tent, and made supper. Looking up from his work he saw that the Major had returned and was sitting on his horse, staring at him strangely. The two ate their evening meal in silence. When they were finished Rogers finally exploded.