The Last Living Slut (4 page)

Read The Last Living Slut Online

Authors: Roxana Shirazi

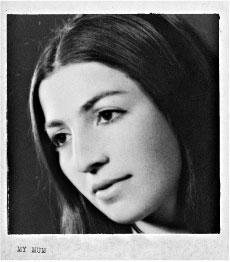

Still, she remained beautiful, with chestnut brown hair fashioned in a bob and honey eyes glistening with natural seductiveness, just like my mother’s. “

Ashraf khanoom

, you’re always dressed so chic,” I’d hear women tell her at

mehmoonis

(family parties). “Is it from Paris?” They’d sniff around her bags and dresses, and she’d always end up giving away one thing or another.

Even though this was the peak of the Shah’s rule, a time when Westernization was being heavily promoted, she still covered her body with a long, flowery

chador

—the Islamic head-and-body covering—when she went out of the house. She didn’t do it for religious purposes but strictly because she liked tradition.

People gathered at our house at night, and Anneh always started the dancing, getting everyone on their feet to move to the Iranian pop songs blasting from the cassette player. She was happy, always singing, always full of light. She welcomed everyone into our home with such genuine love and warmth that I wondered if anything ever really upset her. I found shelter in her lap and heaven in her protection when I put my head against her fat tummy, hearing the clutter of her insides and sniffing the faint smell of her Western perfume, while my mother went to work every day teaching teenagers at the local school.

My mother had a psychology degree and taught literature, psychology, and Arabic, leaving early in the morning and coming back at dusk. She had gone back to work four weeks after giving birth so she could provide for me and my grandmother. Sometimes her breast milk seeped through her shirt mid-lecture.

In many ways, my mother was the opposite of my grandmother. Even though she was only in her mid-twenties, she was serious, quiet, and pensive—and an active revolutionary. She’d rush home from work and demonstrations to do chores, pay bills, find doctors, and fix the home.

“Don’t forget the duck-shaped bread,” I would yell after her as she left the house. She never did forget to bring back a piece of duck-shaped brioche. I remember waiting for that bread with uncontrollable joy rushing through my body.

My mother shunned makeup and fancy clothes, embracing simplicity and somber colors as a revolutionary stance. The only beauty routines she adored were ironing her hair fire-poker straight with the household iron and waxing her legs to gleaming marble smoothness with homemade wax.

“Here, help me rip these sheets, my darling,” she said one afternoon, looking up from the fraying garments strewn around her on the floor, gooey, yellow, hot wax on her leg and spatula in hand.

Rip, rip, rip

, went the old sheets to become strips for her legs. I watched my mother squeal in pain for the sake of beauty as she applied and then ripped the cotton strips away.

“I wanna do it!” I whined. I wanted to be glamorous, too.

“Not until you’re twenty,” my mother snapped, tending to her slim white legs. She wanted me to be a child, not to rush into womanhood. But by the age of five I already loved makeup. I was obsessed with dressing up in the latest fashions, and desperately wanted platform shoes and flared trousers.

I screamed and howled, driving my poor mother to tears. As far as I was concerned, it was detrimental to my existence to be denied a pair of platform shoes. And my mother went mad if I touched makeup, so when she was off at work and my grandmother had her afternoon siesta, I would sneak into my grandmother’s makeup bag and cream on her neon-pink lipstick and chalk on nightclub-blue eye shadow.

We hardly had any money, but I was a spoiled princess. Everyone in my family doted on me, especially my grandmother, who bought me so many dolls that they overtook the living room and made for quite a lively tea party. Still, I stamped my feet and cried through my whistling snotty nose because it wasn’t enough. I wanted her to buy me a bride doll that I’d seen in a shop window.

Even then, I always wanted more than I had.

E

very morning, after my mother left for work, my grandmother and I began our day. First I’d run to the neighborhood bakery to get

nooneh sangak

—a foot-long triangular bread the man would bake while I watched. They would throw a slab of dough into the clay oven. It was still steaming when they brought it out, with tiny stones from the oven clinging to its underside. As they folded it, they would tell me to watch my fingers, but I didn’t care; I let the hot bread sting my mouth as I gobbled it down while running back to the house.

When I got home, we’d have breakfast sitting around the

sofreh

—an oil cloth spread on the floor for serving food—or sit by the fishpond in the garden. On the sofreh, feta cheese, herbs, fresh double cream, honey, and sour cherry jam were laid out with the hot tea. My grandmother brewed tea in the

samovar

, an hourglass-shaped decorative metal container that boiled water as steam escaped from its head, allowing the tea to brew slowly.

After the dawn prayer, an old, toothless lady by the name of Masha Baiim would come by most mornings to help my grandmother around the house. Her face was a brown, weathered map etched with deep lines. She had the patience of a saint and long black hair, which she wore in two braids hanging by her waist like rope. I was generally horrible to her, giving her hell and the occasional bite on the arm when she wouldn’t let me do the things I wanted to do.

After breakfast, I would go out to play with my friends in the alley. All the neighbors in the little houses knew one another. Our mud alley was always sunny and orange. Then we would roam the

maidoon

—or square—in the center of the neighborhood. In Tehran, every square had a number and was the social hub of the surrounding area.

By the time the sound of noon prayer wailed from the nearby mosque, the neighborhood buzzed with activity. The first to arrive was the salt seller, an old man who hobbled through the alley croaking “

Namaki! Namaki!

” (“Salt seller! Salt seller!”) and selling the raw rock salt he carried in a sack on his bent back. A few women would bring out scraps of dried bread, leftover food, or sometimes unwanted clothes to exchange for a piece of rock salt. I remember feeling lucky that I wasn’t as poor as the salt seller, whose skinny face would break into a humble, toothless grin as he collected the goods and sauntered off to the next street.

We played until the traders arrived at noon with their cartfuls of merchandise. In the winter, the beetroot seller wheeled his cart to a stop at the top of the alley. I would run to get coins from my grandmother. Peeling off the dirty outer layer of the cooked beet would expose the steaming hot flesh beneath. My teeth sliced through the chunks and I let the hot juice wash over my gums. The tamarind man was there year-round, selling us lovely sour-salty tamarind. In the spring came a man with

gojeh sabz

—small unripe sour green plums—which we would sprinkle with salt and eat until our stomachs ached.

Sometimes, in the middle of a hopscotch game, the cinema-rama man would appear. He’d wheel in a big box. We’d put coins in, look in a peephole, and be transported to another world. A world of corseted ladies with pink boas, fancy lace, and exotic hairbrushes. When the time ran out, we’d beg the adults for more money so we could exist just a little longer in

Shahreh Farang

(foreign city). I’d peer into it so deeply that my left eye would be bruised. And then my coins would run out.

“You can’t have money for this

and

the wheel!” my mother or grandmother would say, looking up from their work cleaning fresh herbs for dinner. I loved the mini Ferris wheel that rolled into the alley once or twice a week. It always drew a massive crowd, even though the top of the wheel rose only ten feet off the ground. It felt grand to sit in those old moldy seats in the sky.

Throughout the day, the sound of mournful prayer from the loudspeaker of a nearby mosque served as a fearful reminder to pray to God. In our home, my grandmother would promptly put on her chador and turn to face Mecca, the holy city. A deep and respectful silence would fall over the neighborhood as the grownups gathered their prayer mats and

Mohr

—a small chunk of holy clay that supposedly came directly from Mecca.

Some days, during the siesta that followed, I played alone in my grandmother’s garden. I felt like a princess there: the garden was my court, the fruit trees ready to serve me. A pomegranate tree, which opened her baby pink flowers in summer, showed the world she was ready to bear autumn fruit. Next to it stood a sour cherry tree—my favorite. Lifting the hem of my dress, I would pluck the tiny cherries and gather them in my skirts. I was greedy for that fruit, even more than the blackbirds who competed with me to fill their bellies first.

At the end of the garden wall rose the tallest fir tree I had ever seen. Its trunk was so wide and its branches so dense with pines that it provided a shield for me and my cousins’ childhood games.

On the left side of the garden were the roses—pink, yellow, and white. Puffy roses. Scarlet buds pursing their lips to the sky in a kiss. Right in the middle of the yard was a small round pond filled with goldfish and green slimy moss. Often I would undress and float naked under the water, holding my breath as long as I could to feel the slither of the fish and slippery moss against my chest and tummy. My cinnamon ringlets were soaked but, soon enough, the crisp Persian sun would toast them dry as I sunbathed naked on the concrete.

“Put some panties on! Bad girl!” my grandmother or mum would scold in a loud whisper if they caught me. But I loved the feeling of my body exposed in the water and the sun. I wanted to be free.

When the adults awoke from the siesta, it was time for early evening tea, which was exactly like breakfast. In the summer we enjoyed tea in the garden. Then, in the evening, everyone put on fancy clothes to go

mehmooni

, visiting relatives’ houses to eat, dance, and have a good time. My mother usually took me to see her sister and my cousins in Foozieh, a seedy part of town that smelled like sewage. We stood by the road and shouted our destination at the orange taxis speeding by—the customary way to flag down a cab—until one stopped and we climbed in, sharing a ride with others headed that way.

Most of the men in my mother’s family were political prisoners, leaving the women alone with their children and forced to stay with their parents or in-laws. My aunt’s husband was a political prisoner along with my uncle and my mother’s cousins. Day and night, the adults would sit talking about the political situation. In the 1970s, Iran emerged as one of the oil giants of the Middle East and the Shah established himself as a monarch, with a plan to Westernize our society. By 1973, Tehran was considered one of the world’s most innovative capital cities, with religion operating on the fringes. Scores of villagers and farmers filtered into Tehran to take advantage of the prosperity promised to them by the Shah. But government corruption ensured that the promised trickle-down of wealth only pooled around government officials and friends of the Shah. The gap between rich and poor rapidly grew wider.

Soon, due to a lack of jobs and housing, an abundance of shantytowns, teeming with disenfranchised villagers and farmers, sprouted up around Tehran. As unrest spread through the citizenry, the ruling body hardened into an even more stringent military dictatorship. The Shah imprisoned anyone with opposing views, and stripped away civil liberties and the right to strike. Freedom of speech and the press were eliminated, and anti-Shah activity was punishable by torture, imprisonment, and even execution. The Shah activated his own secret police—the savak—who ramped up terror by raiding homes believed to house anti-Shah literature and arresting all suspects encountered on the way.

In this turbulent political state, dozens of resistance groups sprang up, many of them with multiple branches. Their ideologies may have differed in their particulars, but they were united in one objective: to overthrow the Shah’s military dictatorship and bring freedom and social equality to the people of Iran.

As public unrest and anti-Shah demonstrations increased, so did the gunfire in the streets. My grandmother’s house began to turn into a base for intensifying political activity. The savak raided houses in our neighborhood daily. And life became more hazardous.