The Last Gun (6 page)

Authors: Tom Diaz

But, as John Adams wrote, “Facts are stubborn things, and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

67

And no matter what may be the greedy passions and self-interested wishes of the gun industry and its highly paid mouthpieces, one stubborn, bloody fact looms above all of their false assertions, impossible to avoid or erase: the United States stands alone in its high level of gun violence, a shocking contrast to other developed nations.

Two detailed cross-national comparisons of firearms deaths among comparable nations of the worldâpublished in 1998 and 2011âarrived at similar conclusions. The 1998 study found that “the US is unique in several aspects. It has the highest overall firearm mortality rate, a high proportion of homicides that are the result of a firearm injury, and the highest proportion of suicides that are the result of a firearm injury.”

68

The 2011 study reported that “the United States has a large relative firearm problem; firearm death rates in the US are more than seven times higher than they are in the other high-income countries. Firearm homicide rates are 19 times higher in the US compared with the other 22 countries in this analysis, firearm suicide rates, and unintentional firearm death rates are over five times higher. Of all the firearm deaths in these 23 high-income countries in 2003, 80% occurred in the United States.”

69

This gun carnage is so, even though “our rates of crime and nonlethal violence are not exceptional.”

70

In sum, a mugging or argument that goes wrong in Hamburg ends up with a few bruises. In Baltimore or a Denver suburb, it may likely end up with someone being shot.

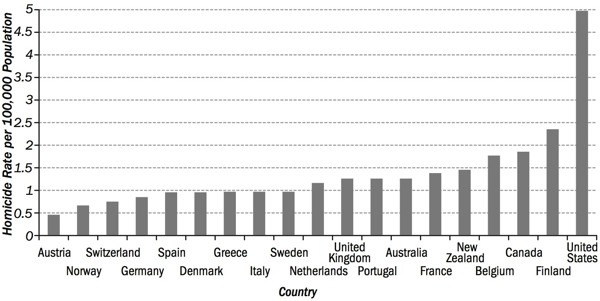

As a consequence of all this, the United States also stands far and away above other developed nations in its homicide rate, as illustrated in

Figure 5

.

Figure 5. World Homicide Rates

How can this be? A closer look at the week of gun violence documented in

figure 2

and

appendix A

provides some powerful clues. The first six deathsâin fact, the only gun deaths reported on the first two daysâwere suicides and murder-suicides.

On Monday, August 1, 2011, in Fort Huachuca, Arizona, a U.S. Army sergeant was found dead in his quarters of a gunshot wound. Base officials would not say whether he committed suicide. However, he had been arrested and escorted back to his quarters by military police the same day for bringing his personal handgun to the base's headquarters.

71

The following day, Tuesday, August 2, in Lee, New Hampshire, Andrew Hubbard, twenty-seven, killed himself with a shotgun after being involved in a car crash. Neither driver was seriously injured in the head-on collision, but Hubbard grabbed a shotgun out of the back seat of his car, then fatally shot himself behind the premises of a nearby business.

72

In Hillsboro, Wisconsin, Joseph C. Satterlee, fifty-five, rammed his wife's car on a street with his own vehicle, climbed into her car, and shot her to death with his .357 Magnum revolver. He then shot himself to death. Satterlee fired a total of eight rounds from his six-shot revolver,

pausing to reload it once. His wife, Anita K. Satterlee, had filed for divorce on June 20, 2011.

73

And in Kensington, Maryland, a quiet, upscale suburb of Washington, D.C., police officers found the bodies of Margaret F. Jensvold, fifty-four, and her son Ben Barnhard, thirteen, in their residence. Investigators concluded that Jensvold, a psychiatrist, had shot her son to death and then killed herself. The son had a number of special needs, and Jensvold was reportedly distressed that the local public school system would not pay for his attendance at a private school.

74

These deaths aptly illustrate a fact that most Americans are surprised to learn. Most gun deaths are not homicides, but preventable suicides. Even in the case of homicide, the most common scenario is notâas the NRA prefers to imagineâa rampaging criminal, but an argument between two people who know each other.

75

In this context, the human cost of the gun lobby's meddling in public policy becomes clear. For example, as is explained in the introduction, the NRA convinced Congress to forbid the armed services from collecting any information about personally owned guns among members of the military and its civilian employees. This law has had tragic yet entirely foreseeable effects. Between 2001 and 2008, 1,531 active-duty members of the military died from self-inflicted wounds.

76

(This number does not include suicides among former members of the military, which are also known to be numerous.) The military has not escaped the infection of suicide that accompanies the widespread availability of guns. But the new law has cut off an important avenue of suicide prevention among both active-duty and former military personnel.

77

In the civilian context, “the empirical evidence linking suicide risk in the United States to the presence of firearms in the home is compelling.”

78

The link is no less compelling among the military, serving and former alike. According to Dr. Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, who recently retired as a high-ranking army psychiatrist directly involved in the issue, “approximately 70 percent of Army

and Pentagon suicides are by guns.”

79

According to a study released in October 2011âominously titled

Losing the Battle: The Challenge of Military Suicide

â48 percent of military suicides in 2010 were accomplished with privately owned weapons.

80

In spite of this, Dr. Ritchie noted, although the army is “committed to lowering the rate of suicide . . . there's a curious third rail that is seldom publicly discussed: the risks of suicide by firearm.” She also notes that Army Post Exchangesâ“basically government-owned Walmarts on major posts”âare increasingly selling guns and asks whether this is “sending the troops the right message.”

81

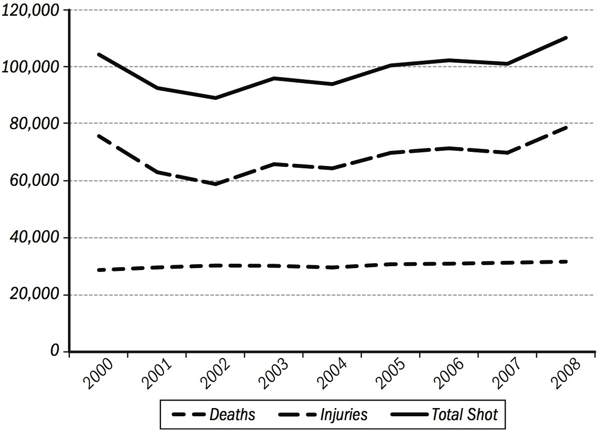

The media's reporting vacuum and the gun lobby's distortions have obscured another fact: the number of shootings in the United States is going up, not down.

The number of Americans killed by guns has remained fairly constant in the nine years for which complete data is available in the twenty-first century

82

But the common focus on gun deaths as a marker to illustrate America's gun problem obscures an alarming trend. The number of persons who suffer nonfatal gunshot injuriesâthat is, who are shot but do not dieâhas risen over the same period. As graphically demonstrated by

figure 6

,

this means that more people are being shot by guns every year in the United States. In other words, America's gun problem is getting worse, not better. More guns means more shootings.

Figure 6. Total Shootings Rising in the United States

Figure 6

shows that between 2000 and 2008 a total of 617,488 people suffered nonfatal gunshot injuries in the United States. This averages about 68,610 persons per year. In 2008, howeverâa year in which gun deaths totaled 31,593, only slightly above the period's averageâanother 78,622 were shot but did not die, a figure markedly above the period's average. Most striking, the total number of people shot in 2008 totaled 110,215âthe highest total recorded during the nine-year period.

83

These civilian deaths and injuries may be put into further perspective by comparing them to the experience of the U.S. armed services during the same period. The total of U.S. active-duty military deaths, from all causes, in the years 2001 through 2008 was 12,390.

84

The total deaths caused by hostile action during the same eight years was 3,811, while the number of deaths from self-inflicted wounds among active duty military personnel was 1,531.

85

Why have gun deaths remained fairly constant even though the total number of people shot is increasing? The answer is that improved emergency services and better medical care are saving lives that would otherwise be lost to guns.

The authors of a landmark study in 2002 on the relationship between murder and medicine concluded that advances in emergency servicesâincluding the 911 system and establishment of trauma centersâas well as better surgical techniques have suppressed the homicide rate. They concluded that “without these developments in medical technology there would have been between 45,000 and 70,000 homicides annually the past 5 years instead of an actual 15,000 to 20,000.”

86

That finding is confirmed by anecdotal observations from law enforcement officials and the medical community. “It would be fair to say gunshot wound victims, if they suffered the same injury 25 years earlier, their chances of survival would be much

less,” Major Pat Welsh of the Dayton, Ohio, police said in April 2011. “It's a credit to the advances in medical technology and procedures.”

87

In Birmingham, Alabama, Dr. Loring Rue, chief of trauma care at the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Trauma Center, said in commenting on the fact that while the number of violent crimes was increasing in Birmingham, the number of resulting deaths was falling, “I am convinced that not just our hospital, but all those who provide trauma care in Birmingham, make a distinct contribution to keeping the murder rate lower.”

88

The bad news is that even nonfatal gunshot wounds often leave victims chronically damaged. “There have definitely been improvements in trauma care, and a remarkable job is being done in getting victims through life-threatening injuries, but we are still being left with injuries that drastically alter lives,” according to Dr. Selwyn Rogers, director of a trauma center in Boston.

89

The January 2011 shooting in Tucson, Arizona, in which U.S. Representative Gabrielle Giffords was gravely injured, is a well-known, if not singular, example. Fifty percent of all trauma deaths are secondary to traumatic brain injury such as Representative Giffords suffered, and gunshot wounds to the head caused 35 percent of these.

90

Gunshot wounds also account for about 15 percent of all spinal cord injuries in the United States.

91

One question that remains unanswered is whether advances in care will outpace advances in gun lethality as the gun industry continues to militarize the civilian market with high-capacity semiautomatic pistols, assault rifles, and high-caliber sniper rifles.

92

“Many of the victims now have multiple gunshot wounds,” then District of Columbia police chief Charles H. Ramsey observed in 2003. “The criminals also use high-caliber, high-powered weapons.”

93

As the authors of the 2002 study trenchantly observed, “At some point in contesting the outcome of criminal assault to the body, weaponry may yet trump medicine.”

94

SUPREME NONSENSE AND DEADLY MYTHS

With the exception of one historic and widely reported event, Thursday, June 26, 2008, was a routine day in the universe of gun death and injury in the United States.

1

The gunfire started well before sunrise.

At about one

A

.

M

., in Corpus Christi, Texas, a man angry about a stolen radio fired at least four shots into the air in front of a residence where he thought the culprit lived.

2

Around two

A

.

M

., twenty-five-year-old Manuel Davis was shot to death on a street corner in Cleveland, Ohio.

3

Half an hour later, at two thirty

A

.

M

. in Halsell, Alabama, Jimmy Tanks, a sixty-seven-year-old railroad retiree, heard noises outside his trailer home and grabbed his gun. The noise was a “repo man” in the process of repossessing Tanks's car.

4

Shots were fired and Tanks was killed. At just about the same time, in Muskegon, Michigan, a twenty-three-year-old woman and her boyfriend were wounded in what police described as a suicide attempt.

5

Less than an hour later, twenty-year-old Bernardino Hernandez allegedly opened fire on his ex-girlfriend in Elgin, Illinois, shooting her three times in the backâthe two were reported to be in a dispute over custody of their baby.

6