The Last Empire (43 page)

Authors: Serhii Plokhy

President Bush meeting with (right to left) Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, Secretary of State James Baker, White House Chief of Staff John H. Sununu, and National Security Adviser General Brent Scowcroft during the First Gulf War in early 1991. A few months later, Cheney clashed with the rest of the Bush team over American policy toward the crumbling Soviet Union. He wanted the USSR gone as soon as possible. (George Bush Presidential Library and Museum)

Time is up. Russian prime minister Ivan Silaev and future Ukrainian president Leonid Kravchuk check their watches as a worried Mikhail Gorbachev looks on. In the fall of 1991 Gorbachev found it increasingly difficult to deal with the two largest Soviet republics. Kremlin, Moscow, 1991. (ITAR-TASS Photo Agency)

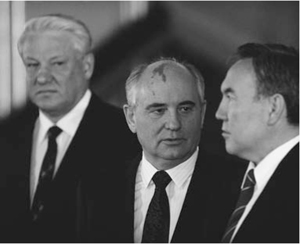

With Russia and Ukraine against him, Gorbachev courts the Kazakh leader, Nursultan Nazarbayev. Both men wanted to preserve the Soviet Union. Here a worried Yeltsin looks on as Gorbachev talks with Nazarbayev during the signing of the economic agreement in Moscow, October 18, 1991. (Corbis)

The Russian ark. Boris Yeltsin shakes hands with his economic guru, Yegor Gaidar. Russia will go its own way, at least when it comes to economic policy. The rest of the republics can follow or get out of the way. Russia would get them back once it saved itself, argued Yeltsin's advisers. Moscow, 1991. (ITAR-TASS Photo Agency)

The survivor. Gorbachev's last appearance on the international scene. Participants in the Middle East Peace Conference descend the stairs of the Royal Palace, Madrid, Spain, October 30, 1991. Behind Gorbachev is his short-lived foreign minister, Boris Pankin; behind Bush is the main architect of the conference, James Baker. In the center is Prime Minister Felipe González of Spain. He told Gorbachev that Bush and other Western leaders had written him off during the coup. (George Bush Presidential Library and Museum)

The Slavic trinity. The leaders of the three Slavic republics decide to dissolve the USSR, Belavezha Hunting Lodge, December 8, 1991. Left to right: the contented Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine, the confused StanislaÅ Shushkevich of Belarus, and the always decisive Boris Yeltsin of Russia. He is bracing himself for a stormy meeting with Gorbachev the next morning in Moscow. (ITAR-TASS Photo Agency)

Bush and Baker, friends and confidants, shown here in November 1990. In the fall of 1991 they decided to back Gorbachev no matter what. In December 1991 Baker traveled to Moscow, Kyiv, Minsk, Almaty, and Bishkek to find out what was actually going on in the Soviet Union. He reported back to Bush, recommending that he endorse the creation of the Commonwealth of Independent States. (George Bush Presidential Library and Museum)

Christmas in Moscow. Gorbachev reads his resignation speech. Now it is official: the last empire has disappeared from the political map of the world. Kremlin, Moscow, December 25, 1991. (ITAR-TASS Photo Agency)

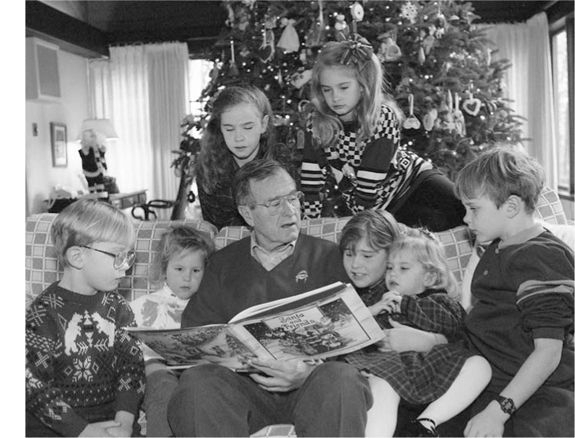

The storyteller. President Bush reads Christmas stories to his grandchildren on December 24, 1991. Next day he would fly to Washington to address to the nation on the occasion of Gorbachev's resignation and declare American victory in the Cold War. (George Bush Presidential Library and Museum)

M

IKHAIL GORBACHEV WAS SITTING

in his office at the government resort of Novo-Ogarevo. It was the afternoon of November 25, eleven days after the previous meeting of the State Council and the day of its next meeting. This time he had done itâhe had not just threatened to walk out on a meeting but had actually done so. Now he was anxious to learn what the next minutes would bring. Much had changed in and around Moscow since November 14, when he put Yeltsin and other leaders of the republics in front of television cameras and had them say that there would be some form of union in the future.

The main change was in the mood of the policy makers. Everyone was awaiting the Ukrainian referendum, scheduled for December 1, and everyone except Gorbachev was predicting a landslide in favor of independence. That was the opinion of the Ukrainian leaders, Boris Yeltsin and his fellow leaders of the republics, and George Bush and his advisers in Washington. Within the next few days, the Ukrainian factor would dramatically change the balance of forces between the republics, their relations with Gorbachev, and Bush's relations with the Soviet leader. The first sign of the coming change was the behavior of the presidents of the republics who gathered in Novo-Ogarevo on November 25 to discuss the new union treaty proposed by Gorbachev.

On that day, they were supposed to endorse the text of the union treaty that they had debated and agreed upon at the previous

meeting of the State Council. Problems began, as always, with Yeltsin, who again raised the question of the nature of the future union. He claimed that the term agreed on last time, “confederative state,” was meaningless. The treaty should stipulate instead the creation of a union or confederation of sovereign states: otherwise the Russian parliament would not ratify it.

The leaders of Belarus, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan supported Yeltsin. They refused to endorse the treaty and offered instead to submit it to their parliaments without their signatures, effectively dissociating themselves from the text. Gorbachev was furious, accusing Yeltsin of going back on his word given at the previous meeting. “So what?” responded Yeltsin, who told the media the day after the November 14 meeting that he had compromised too much. “Time is passing. In groups and committees of the [[Russian]] Supreme Soviet . . . [[the text]] was discussed, and they say that such a draft will not make it through.” As if that were not enough, Yeltsin pointed to the elephant in the roomâthe absence of representatives from Ukraine. He doubted that Ukraine would agree to join a “confederative state.” “There will be no union without Ukraine,” declared Yeltsin.

The Speaker of the Belarusian parliament, the fifty-six-year-old StanislaÅ Shushkevich, a member of the Belarusian democratic opposition and an opponent of the August coup, argued that the republican leaders needed ten more days to study the treaty because of its importance. The postponement would also make it possible for Ukraine to join. “Let's wait until December 1,” suggested Yeltsin. Gorbachev tried to turn the Ukrainian factor around. “If we decline,” he said, referring to the endorsement of the union treaty, “it will be a gift to the separatists.” His argument fell on deaf ears. Gorbachev finally lost his nerve and decided to resort to his tried-and-true maneuver of threatening to leave. “If you consider the agreement unnecessary, say so clearly,” he told the republican presidents. “Perhaps you should meet separately and decide. Or stay here, and we shall leave you. . . . Get a feeling for what is more important to youâthe people or the separatists.” With a few more parting words, he left the room, accompanied by his assistants.