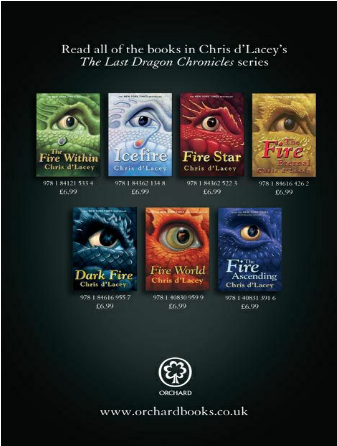

The Last Dragon Chronicles: The Fire Ascending

www.orchardbooks.co.uk

ORCHARD BOOKS

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

Orchard Books Australia

Level 17/207 Kent Street, Sydney, NSW 2000,

Australia

ISBN 978 1 40831 659 7

First published in Great Britain in 2012

This ebook edition published in 2012

Text © Chris d’Lacey 2012

Interior illustration © Tim Rose 2012

The right of Chris d’Lacey to be identified as theauthor of this work has been asserted by him inaccordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

Orchard Books is a division of Hachette

Children’s Books,

an Hachette UK company

www.hachette.co.uk

for Zookie

“Time is like water, it finds its own levels… ”

the sibyl, Gwilanna

And men will say to themselves, “Whatbecame of the last true dragon, Gawain? Did he die in flames upon the sword of awarrior? Did he spread his wings and flyinto the sun, leaving naught but hisperfect shadow behind? Did he cloakhimself in the ash of a volcano ready toemerge in glory one day?”

These stories, I can tell you, are all aninvention. The truth is he died ofloneliness. Solitude clawed at his achingheart and drew his fire to the cusp of hiseye. His auma gathered in a single teardrop. And when he could no longer bearto look upon a world untouched by the

beauty of dragons, he closed his eye and

his fire tear fell.

Herein lies the way of it…

from

The Book of Agawin

A History of Dragons

Part One

Voss

I was a boy of twelve when I watched adragon die. It was during the season ofwinterfold, when every morning thehillsides were brittle with frost and the

peak of Kasgerden shone bright with snow. I was a cave dweller then, in the keep of Yolen the healer and seer. One morning, while I was tending a goat, the earth shuddered and the pointed shadow of the beast swept over the valley, bending every blade of grass to its will. The goats were disturbed and came together in a flock. They knew better than I that a dragon was near. I jumped up, spinning about. Between the clouds there was only pale pink sky. But I could hear the quiet scything of wings and smell the

burnt sulphur trail the beast was leaving, falling all around like unseen drizzle. Swiftly, I gathered my robe about my knees and hurried for the cave as fast as I

could. Behind me the goat bells rattled. There was nothing I could do to protect the flock. If the dragon had wanted them, it could have had them all.

But killing was not on its mind that day. As I ran up the scree, calling out to Yolen,he was already standing at the mouth ofthe cave, staring hard across the yawningvalley. His lips were drawn. There was athoughtful look in his watery eyes. Heraised a hand to tell me I should stop mypanting. “Be calm, boy, there is nodanger.”

“But it’s… a

dragon

,” I blustered, my

youthful voice overflowing with wonder. The beasts were so rarely seen these days. This mountain range had once been a breeding ground for them. They were legend here. Yolen himself had taught me this.

I saw him nod. His gaze narrowedslightly. “Then be quiet and

observe

it. This might be the only chance you’ll get.”

And I understood perfectly what he

meant. Whenever men spoke about dragons these days, they spoke of them as if they were a finished breed.

So I sat upon the scree and I peered at the mountain. On the tip of Kasgerden I saw the beast in frightening silhouette. It was standing on a pair of stout hind legs with its wings stretched fully and its long

neck funnelled at the drifting clouds. I saw no flame, but out of its mouth came a cry I was sure would sever the air. I wanted to

press my hands to my head, but Yolen had not moved to do the same and I did not

wish to seem weak in his presence. So I bore the beast’s rippling wail in my ears and tried, instead, to listen to its voice and make sense of its call.

Long ago, Yolen had taught me that allthings natural to the earth had

auma

. Thegreat life force, Gaia, moved within themost inanimate pebbles as well as throughthe river and the mountains – and me.

Even the smallest grain of earth wasaware of its presence in the universe, said Yolen. In essence, we were all one being,born from the fire of the true Creator

(though he had yet to teach me who or what that was). This was a truth all men possessed but few knew what to do with, he would say. That day, I relaxed my thoughts and gave my auma up to the earth so I might

commingle

with the dragon on the mountain. I built a picture in my mind from that distant silhouette and let the

squealing enter my head. And long before my master had dropped his confident hand upon my shoulder, I knew what Yolen knew already.

“It’s come to Kasgerden to shed its fire tear.”

“Go to the cave. Gather food and

clothing. There will be a pilgrimage,”

Yolen said.

I looked once more at the creature. It

had not come hunting, it had come here to

die.

And I was going to witness it.

That day, I became a follower of Galen.

I had no idea when we set off down the

valley that this was the dragon’s true or real name. That I would learn from the

mouths of other followers. The sun had

barely moved through the narrowest of arcs when our path began to cross with a host of them, all making their way, like us, to Kasgerden. Yolen had led us straight to the river, which ran in a curve through the forest we called Horste. From between

the Horste pines the pilgrims were descending, as if the trees themselves had lifted their roots and were moving as one towards the water and the mountain. They

were simple folk, dressed in robes or common tunics. They wore sandals made of goat hide, and furs around their shoulders. I envied their children, who grew their braided hair far longer than mine and wore necklaces and bracelets

made from cones and other seeds. Some of

the men, I noticed, bore spears.

The name ‘Galen’ bubbled up as we joined their throng. The last dragon from the Wearle of Hautuuslanden. A male. A

bronze with white undersides – a feature

that marked the beast down as old. Three

hundred years at least. Maybe more. The men argued constantly about this fact. I heard one of them suggesting that the beast might not be old, but weakened. That its scales were losing their colour due to

some unusual condition or disease.

(Yolen, I saw, took note of this.) But there was one thing they were in agreement on. There would be

fraas

, they kept saying. Fraas. Fraas. The sheer thrill of it glinted in their hungry eyes. They shook their spears and gave praise to Gaia. There was a dragon. And there would be fraas.

This word, like the dragon’s name, was new to me then. I tugged Yolen’s sleeve. “What is ‘fraas’?” I asked him.

He drew me aside, close to theriverbank, a little away from the body ofthe followers. “It has been known,” hesaid, “for a dragon to shed sparks when itstear is released or first strikes the earth.