The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA (15 page)

Read The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA Online

Authors: John Ashdown-Hill

There has been some confusion about the name of Richard III's last battle. However, there seems no particular reason to reject the traditional âBosworth Field', since Henry VIII so referred to it in 1511.

12

In addition, âthere have been as many different accounts of Bosworth as there have been historians, and even today it is hard to produce a reconstruction of the battle which will command general acceptance'.

13

Ross and other modern writers continue to stress the numerical superiority of Richard III's army over âthe mixed force of French and Welsh levies which was all Henry “Tudor” could command'.

14

While the smallness of the âTudor' force may later have been exaggerated to point up the scale and miraculous nature of Henry VII's victory, superficially the respective numbers appear to suggest that Henry âTudor' had not succeeded in attracting any significant English support, and that the only English on his side were probably the small number of exiled noblemen who had formed his entourage in France.

As we have already observed, Richard III's army probably camped in and around Sutton Cheney. Let us now attempt to reconstruct the events of the last few hours of Richard III's life.

In the royal camp, the king probably arose soon after monastery and convent bells had sounded the hour of Prime, at about ten minutes past six (BST) on the morning of Monday 22 August.

15

As we have already seen, reportedly there were slight delays in the preparations for his morning mass and his breakfast. Let us assume that these delays took up some thirty minutes. The celebration of low mass in the royal tent will then have begun at about 6.40 am. The Bosworth Crucifix (a standard gilt and enamelled piece of royal travelling chapel equipment) mounted upon its lobed base, and with its side brackets in place, bearing figures of the Blessed Virgin and St John, stood, perhaps, on the portable altar, flanked by candlesticks. One of the royal chaplains began intoning the opening words of the mass for the feast day of SS Timothy and Symphorian. He was probably vested in the blood-red chasuble appropriate for the commemoration of martyrs.

16

The Latin words of the introit may have reminded the king of his coronation, and of the crown that he had worn the previous day, and would shortly put on again.

17

The service will not have taken more than half an hour. Thus, by ten past seven, Richard will have been consuming his modest breakfast, probably comprising bread and wine. While he did so his esquires no doubt began to put his armour on him. At the same time, the royal chaplains were dismantling their portable altar in the royal tent. For the last time ever, the Bosworth Crucifix was taken off its lobed base, its side brackets were removed, and it was remounted upon a tall processional stave. A hinged ring of iron was clipped into place at the foot of the crucifix, just above the socket where the latter was now attached to its wooden shaft. To this the chaplains may then have tied ribbons or tassels in the Yorkist royal livery colours of murrey and blue.

18

It was perhaps just after half past seven in the morning when the king finally donned an open crown, probably of gilded metal, set with jewels or paste, which he put on around the brow of his helmet. Richard III then left the royal tent to address his army. His chaplains, bearing the Bosworth Crucifix (now mounted as a processional cross), accompanied him to bless the royal forces.

It seems to have been a bright, sunny morning.

19

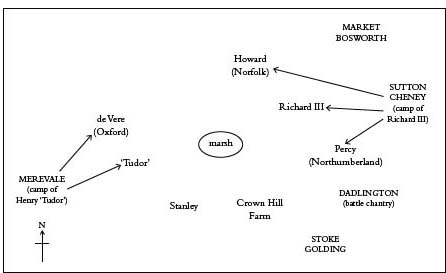

The enemy army had spent the night about 5 miles away at Merevale, which is located on Watling Street â a direct route to London. Richard, therefore, left his camp and marched his own forces westwards. The king's aim was to block Henry Tudor's route to London. However, Richard did not march as far as Watling Street. This was possibly because a Stanley banner was already visible to the south-west of Dadlington, near Stoke Golding. The Stanleys' precise intentions were still unclear, but it would have been wise to treat them with caution, and Richard would not have wanted to position his army confronting Henry âTudor', but with the Stanley forces lurking behind him.

Richard, therefore, positioned himself to the north-west of Crown Hill (as it would later be called). There, he arranged his force in an extended line on high ground, with the Duke of Norfolk's forces to the north-west, and the Earl of Northumberland's men to the south-east of the central contingent, which was commanded by Richard himself. Probably by seven fifty or thereabouts, the royal host had taken up its position on a low ridge. According to the Crowland Chronicle, Richard then ordered the execution of George Stanley, Lord Strange, but this execution was certainly not carried out, and the order may never have been given, since the Stanleys had so far taken no overtly hostile action.

20

M

AP

1: The Battle of Bosworth.

On the lower ground in front of Richard's army some of the terrain was marshy.

21

As the king and his men gazed down they saw Henry âTudor''s much smaller force mustered beyond this marshland. Towards eight o'clock this smaller rebel force slowly began to advance towards the royal army, skirting the boggy ground. For a time the king took no action, but eventually, seeing that the rebel forces were clearing the marshland, he gave orders to oppose their further advance.

When John de Vere (

soi-disant

Earl of Oxford, and one of Henry âTudor''s most experienced commanders) saw men of the royal army advancing to oppose them, he swiftly ordered his men to hold back and maintain close contact with their standard bearers. In consequence, the rebel advance may have more or less ground to a halt, but by maintaining a fairly tight formation Henry âTudor''s men effectively prevented any serious incursion into their ranks by the royal army. In total, all this slow manoeuvring may have taken up as much as an hour.

It was apparently at this point â when in religious houses throughout the land monks and nuns, canons and friars were beginning to sing the office of Terce

22

â that the king suddenly caught sight of his second cousin, Henry âTudor', amongst the rebel forces.

23

Perhaps out of bravado; or from a sense of

noblesse oblige;

from fury at seeing âTudor' displaying the undifferenced royal arms, or possibly because he was suffering from a fever and not in full possession of all his faculties, Richard called his men around him and set off with them in person, at the gallop, to settle Henry's fate once and for all. An eyewitness account reports that âhe came with all his division, which was estimated at more than 15,000 men, crying, “These French traitors are today the cause of our realm's ruin”'.

24

The king's action could be seen as a risky move, and one which suggests that Richard may not have been thinking very clearly. In some ways it recalls his father's

sortie

from Sandal Castle, which had led to the Duke of York's death in December 1460. But unlike his father, Richard was in command of a large army and he should have had every chance of winning his battle. Jones prefers to see his charge as âthe final act of Richard's ritual affirmation of himself as rightful king', and it was certainly an action fully in accord with the late medieval chivalric literary tradition.

25

Whichever interpretation is correct, the king's dramatic charge did come very close to succeeding. The force of his charge cut through the âTudor' army, and Richard engaged his rival's standard bearer, William Brandon, whom he swiftly cut down. The âTudor' standard fell to the ground, and at this point Richard's hopes must have been high indeed, since probably only Sir John Cheney now stood between him and his adversary.

But Henry âTudor''s foreign mercenaries now suddenly deployed themselves in a defensive manoeuvre never hitherto witnessed in England. They fell back, enclosing Henry in a square formation of pikemen, through which the mounted warriors of the king's army could not penetrate.

26

The forefront of Richard's charging cavalry suddenly stalled, and the men riding behind cannoned into them. Many must have been unhorsed as a result. Seeing the royal charge thus broken in confusion against the wall of pikemen, the treacherous Stanley now took a swift decision and committed his forces on the âTudor' side.

27

His army cut more or less unopposed through the muddled

mêlée

of the royal cavalry, and in minutes the balance of the field was reversed. Richard III's horse was killed beneath him, and the king fell to the ground, losing his helmet in the process. He was struck on the head. As he struggled to his feet, one of his men offered him his own mount and shouted to Richard to flee, so that he could regroup and fight again. But the king refused. Surrounded now by enemies, he received further blows to his exposed head. His body, still protected by plate armour, was safe, but one hefty blow to the back of his unprotected skull was fatal. Given that in one sense his defeat and death clearly lay at Stanley's door, the report that Richard III's dying words were âTreason â treason' may well be true.

The king had died some six weeks short of his thirty-third birthday. Polydore Vergil's account of his death recorded simply that âking Richerd, alone, was killyd fyghting manfully in the thickkest presse of his enemyes'.

28

Although this account was written by and for Richard's enemies, it is a fitting tribute. Interestingly, it is also one which, in the final analysis, acknowledges without question the one key point which Richard himself was defending, namely his kingship.

Meanwhile, the rest of the vast royal army, most of whom had as yet done no fighting whatever, watched aghast as their sovereign fell. The quick-thinking John de Vere now seized the initiative. Taking rapid advantage of the new situation he hurled himself and his men at the position defended by his cousin, the Duke of Norfolk (who was in command of the royal archers). As de Vere grappled with his cousin, the latter unluckily lost his helmet. It was in that instant that an arrow, loosed at a venture, pierced the Duke of Norfolk's skull and he too fell dead.

29

The vast royal army was now, in effect, a leaderless rabble. As the great host began to disintegrate, and its individual men-at-arms started to flee in the direction of Dadlington, the men of the smaller Tudor army began to pursue them and cut them down. The premise that the final stages of the combat were located in the vicinity of Dadlington is based upon the known fact that Henry VIII later established a perpetual chantry at Dadlington parish church for the souls of those who had been killed in the battle.

30

By about ten o'clock in the morning the fighting was over. It was only from this point onwards that Henry âTudor' would have had the leisure to detail a search for Richard III's body, which had been left lying where it fell, somewhere near Henry's position at the outset of the battle. We shall explore in detail what happened to the king's remains in the next chapter.

Ironically, it was apparently in the month of August 1485 that Richard III's marriage negotiations in Portugal finally came to fruition. We have seen already that the Portuguese Council of State, meeting in Alcobaça, had urged both their king and their infanta in the strongest possible terms to accede to Richard III's marriage proposals, for they feared that otherwise the English court would turn its attention to Castile and Aragon, in which case the âCatholic Kings' were only too likely to agree to a marriage between King Richard and the Infanta Doña Isabel de Aragón.

Duly impressed by his councillors' arguments and prognostications:

King John bullied and brow-beat his sister, but also employed their aunt, Philippa, to try more feminine means of persuasion. A dramatic dénoûment [sic] followed. Joanna [sic] retired for a night of prayer and meditation. She had either a vision or a dream of a âbeautiful young man' who told her that Richard âhad gone from among the living'. Next morning, she gave her brother a firm answer: If Richard were still alive, she would go to England and marry him. If he were indeed dead, the King was not to press her again to marry.

31