The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (17 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

The first few turkeys were brought over by the Spanish, but it was the Portuguese rather than the Spanish who did the most to introduce the turkey to Europe. And it was the Portuguese government policy of secrecy that more than anything caused the misnaming of turkeys that persists to this day.

It all began because of spices. The world emporium for spices at this time was the city of Calicut in Kerala, India, where black pepper from the hills of south India and spices from the Spice Islands were sold to Muslim traders who shipped them to the Levant (the eastern Mediterranean) via Yemen or Hormuz. Then the Ottomans and Venetians took over, controlling the reshipment of spices, and other goods like exotic animals from Africa, to the rest of Europe.

In an attempt to break the Ottoman and Venetian monopolies on this trade, Portuguese mariners, starting with Vasco da Gama in 1497, sailed around Africa to reach Calicut directly by sea. On the way, they established colonies in the Cape Verde Islands and down the coast of West Africa, a region they called Guinea, slave-raiding and trading for ivory, gold, and local birds like the guinea fowl. Reaching Calicut in 1502, they quickly began to import spices as well.

At the same time, the Portuguese acquired turkeys from the Spanish. The Spanish origin is clear in the Portuguese name for turkeys,

galinha do Peru

(Peruvian chicken). The

Virreinato del Perú

(the Viceroyalty of Peru) was the name for the entire Spanish empire in South America, modern-day Peru, Chile, Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina. The Portuguese most likely got

turkey from the mid-Atlantic trade islands

(the Canary or Cape Verde islands) where ships stopped to provision between the Americas, Africa, and Europe.

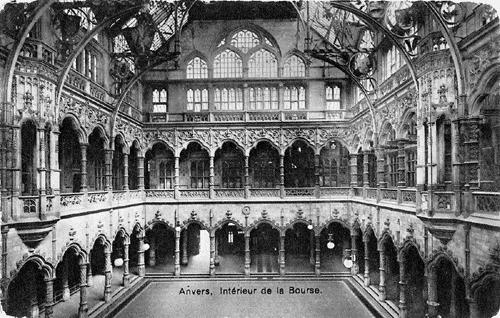

Portuguese ships sailed back to Lisbon with products from all three colonial territories: spices and textiles from Calicut; ivory, gold, feathers, and exotic birds from West Africa; and turkey and corn from the Americas. Customs were paid in Lisbon, and then goods were shipped out again to Antwerp, the trading capital of northern Europe at the time. Sixteenth-century Antwerp was a bustling commercial metropolis experiencing its golden age and full of traders: the Portuguese with their colonial finds, the Germans with their copper and silver products, the Dutch with their herring, and the English, the largest contingent, with their textiles.

In Antwerp, the Portuguese maintained a trading station and warehouse called a

feitoria

in which goods were stored (this is also the original meaning of our English word

factory

).

The trader would bring goods

to various open-air markets in squares throughout the city where wholesalers from the major trading nations of Europe would come and bargain for the Portuguese pepper, ivory, grain, and birds, German silver, English textiles, Dutch herring and so on, presumably amid cacophonies of squawking turkeys and piles of goods and food.

The Antwerp Bourse, from a nineteenth-century postcard using Antwerp’s French name, Anvers

By the middle of the century exchange trading moved to the newly built Antwerp Bourse, the world’s first building built specifically for financial and commodities trading, and from which both French and English get the word

Bourse

, meaning trading exchange. The exchange

enabled common pricings to be established

, and because goods could be sold by sample or even sight unseen, everyone avoided a lot of messy bird droppings.

Meanwhile, France and England had been importing a satiny black African bird that looked extraordinarily similar to a small female turkey. Known today as a guinea fowl, the French and English first called this bird

galine de Turquie

(Turkish chicken)

or

Turkey cock

, after the originally Turkish Mamluk sultans who first sold the bird to the

Europeans in the 1400s

. It was also called

poule d’Inde

(hen of India) because it was imported from Ethiopia (in the fifteenth century, “India” could mean Ethiopia as well as India).

By 1550 the Portuguese began to reimport this African “turkey cock” guinea fowl from West Africa (where there are long oral traditions of breeding guinea fowl among the Mandinka and the Hausa) at the exact same time as they were shipping turkeys from the New World. Both quickly became sought-after commodities.

At the same time, the Portuguese government imposed strict secrecy on all of its maritime explorations, with the goal of protecting its advantage in international trade. Publication of its discoveries was forbidden and maps and charts were strictly censored.

Portuguese globes and nautical charts

were not allowed to show the coast of West Africa, navigators were subject to an oath of silence, and the death penalty was prescribed for pilots who sold nautical charts to foreigners. It was thus impossible to know that one bird came from the Americas and the other from Africa. Because Portuguese goods were routed through Lisbon to pay customs, the two birds may have arrived at Antwerp on the same Portuguese ships, and might even have been traded sight unseen to the English or Germans in the new bourse. The two similar-looking birds were frequently confused, in Antwerp and throughout Europe.

The result is that the English “turkey cock” or “cocks of Inde,” and the French “poules d’Inde” were used sometimes for turkeys, sometimes for guinea fowl, for the next hundred years. The two birds were

confused in Dutch

too, and even Shakespeare sometimes got it wrong, using “turkey” in Henry IV, part I (act II, scene 1) when he meant guinea hen.

The English confusion between the two birds was only resolved when both were commercially farmed in England. In any case, our modern word arrived just in time for “turkey” to be actually eaten in the Renaissance, thus explaining the ubiquity of giant turkey legs in today

’

s “Renaissance Faires.”

Other languages were left with a similarly confused atlas of names; French

dinde

from “d’Inde,” Dutch

kalkeon

, many names (like Polish

indik

) dating from later reference to the Americas as the West Indies, and Levantine Arabic

dik habash

alone still pointing to Ethiopia, the source of the guinea fowl. German used to have a dozen names for turkey (

Truthahn

,

Puter

,

Indianisch

,

Janisch

,

Bubelhahn

,

Welscher Guli

, etc.).

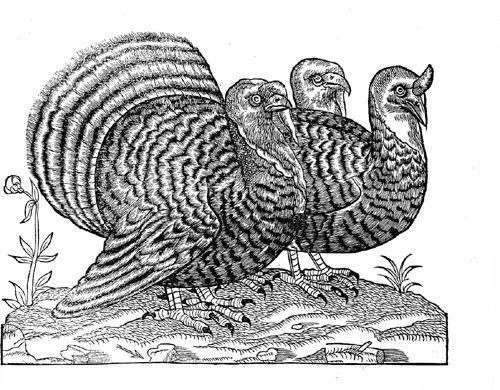

French naturalist Pierre Belon’s drawing of turkeys (“Cocs d’Inde”), from his 1555 book

L’Histoire de la Nature des Oyseaux (The Natural History of Birds)

Another memorial to the early confusion remains in the genus name for turkey that Linnaeus, the Swedish zoologist who is the father of modern taxonomy, mistakenly took from the Greek name for guinea fowl:

meleagris

, explaining Sophocles’ chorus of “turkeys.” Ovid tells us that the name

meleagris

for guinea fowl came from the Greek hero

Meleager

, who was foretold at birth to live only as long as a log burning in his mother’s fire. Although his mother saved the log, Meleager later met a tragic end anyhow and his black-clad sisters cried so many tears over his tomb that

Artemis turned them into guinea fowl

,

Meleagrides

, changing their tears into white spots all over their bodies.

The turkey became particularly popular in England. It was eaten widely by the 1560s and was a standard roasting bird for Christmas and

other feasts by 1573, when a poem celebrated: “Christmas husbandlie fare . . . pies of the best, . . . and

turkey well drest

.”

It was just at this time that the turkey made the journey back to the United States. The English colonists brought domestic turkeys with them to Jamestown in 1607 and the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629, and in both places

compared the “wilde Turkies”

to “our English Turky.”

You probably know that the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony didn’t really have a “First Thanksgiving” turkey feast (although they certainly ate a lot of wild turkey). While there were many days of thanksgiving declared at different points in the American colonies, a day of thanksgiving for the passionately religious Separatists would have been a religious holiday to be spent in church, not a dinner party with the neighbors. Instead, the joint feast to which “Massasoit with some ninety men” brought five deer is described in a 1621 Pilgrim letter as celebrating “our harvest being gotten in,” and

owes more to the autumn harvest festivals

long celebrated in England.

So if the English and the Wampanoag did eat turkey together at that feast (and we may never know for sure), it was not a newly invented American ceremony, but a fine old English tradition of Christmas and festival roast turkey celebrations.

Thanksgiving itself took hold partly from the efforts of Sarah Josepha Hale, a prominent nineteenth-century magazine editor, antislavery novelist, and supporter of female education (and the author of the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”) whose activism for a national day of thanksgiving to unify the country eventually convinced Abraham Lincoln in 1863. Within 20 years

Thanksgiving was linked in schools and newspapers with the Pilgrims

and the schoolchildren of our great immigrant wave of 1880 to 1910 (including my Grandma Anna) brought home a new holiday, a metaphor of gratitude for safe arrival in a new land.

Or at least they brought home the desserts. Like the mestizo mole, the sweet dishes that grew to symbolize Thanksgiving combine New World ingredients (cranberries, sweet potatoes, pumpkins, pecans)

with the medieval spices, sweet and sour flavors, and custards that date back to the Arabic influence on Andalusia and Italy.

By 1658 an English pumpkin pie recipe

with eggs and butter was flavored with sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves, sliced apples, and also savory spices like pepper, thyme, and rosemary. Our modern American pumpkin pie appears in the first cookbook written by an American, Amelia Simmons’s 1796

American Cookery

:

One quart stewed and strained, 3 pints cream, 9 beaten eggs, sugar, mace, nutmeg and ginger, laid into paste . . . and baked in dishes three quarters of an hour.

Recipes for pecan pie are more recent. The earliest I have seen, called Texas Pecan Pie, appeared in

The Ladies Home Journal

in 1898 (pecan is the Texas state pie):

One cup of sugar, one cup of sweet milk, half a cup of pecan kernels chopped fine, three eggs and tablespoonful of flour. When cooked, spread the well-beaten whites of two eggs on top, brown, sprinkle a few of the chopped kernels over.

The milk, eggs, and sugar in these early recipes (corn syrup only came later) remind us that the original pecan pie, like pumpkin pie, was really a custard, a descendant of early European recipes for custard pies. Recipes for an open-topped

pie crust filled with egg yolks, cream

, and spices appear in fifteenth-century cookbooks from both England and Portugal. You can still find them as

pastel de nata

in Portuguese bakeries, and the Portuguese brought them to Macao, where

they became hugely popular by their Cantonese name

daan tat

or “egg tarts.” Egg tarts are now a mainstay of

dim sum

and many Chinese bakeries sell both a Portuguese and a Chinese version. You can even get them at KFC in Macao now. Here in San Francisco, it’s the Golden Gate Bakery on Grant Avenue whose egg tarts make an excellent dessert addition for a Chinese American Thanksgiving.