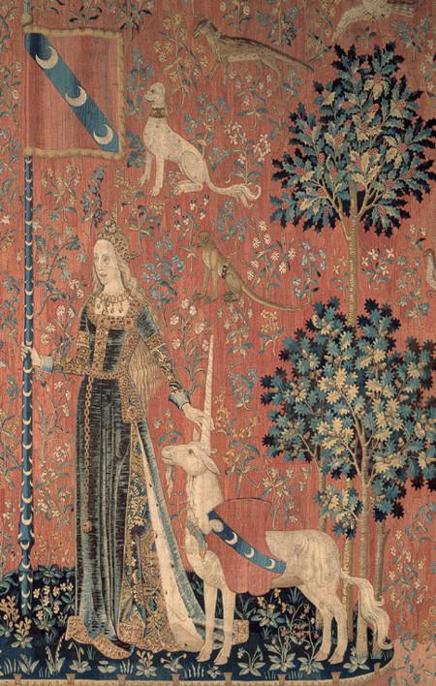

The Lady and the Unicorn (15 page)

Jacques Le Bœuf took a great gulp of pie — he didn't seem insulted by Georges walking away from him as he ate.

I backed away as well, and went to find Madeleine. She was bent over the lentil pot, her face red from the heat. ‘Don't you say a word to Aliénor,’ I hissed. ‘She doesn't need to know about this just now. Besides, nothing has been decided.’

Madeleine glanced up at me, tucked a stray clump of hair behind her ear, and began scrubbing again.

Jacques ate half of our pie before he left. I didn't touch it — I had no stomach for it now.

Aliénor didn't say anything when I fetched her from the neighbour's — she went straight to her garden and began picking the basket of peas for the baker. I was glad, for I don't know what I would have said.

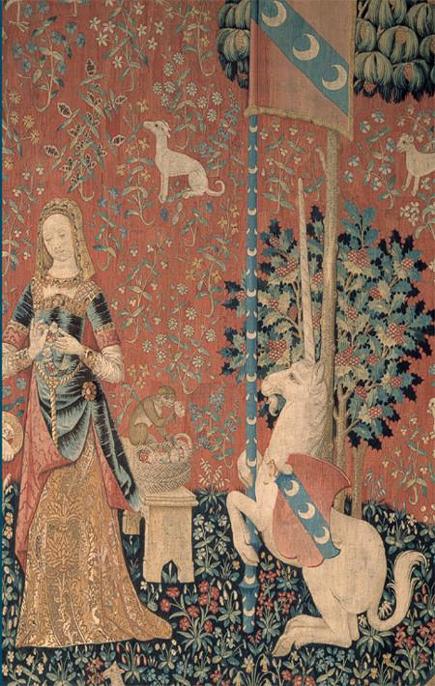

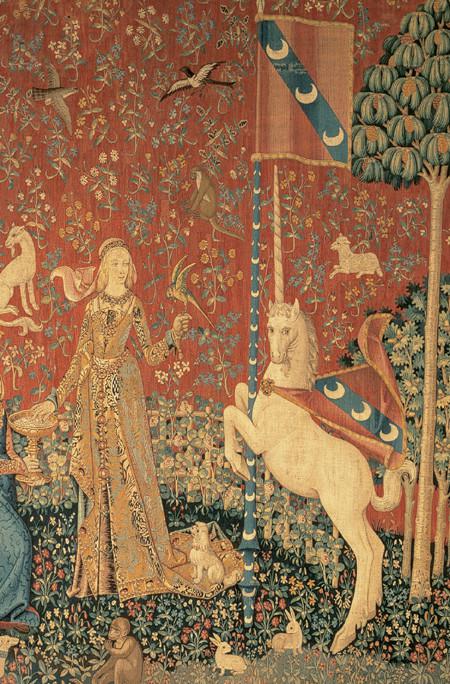

Later she offered to take the peas to the baker's wife on her own. When she was gone I pulled Georges to the far end of the garden by the rose-covered trellis so that no one could hear us. Nicolas and Philippe were working side by side on Smell, Nicolas painting the Lady's arms while Philippe began the lion.

‘What are we going to do about Jacques Le Bœuf, then?’ I demanded.

Georges gazed at some pink dog roses as if he were listening to them rather than me.

‘

Alors

?’

Georges sighed. ‘We will have to let him have her.’

‘The other day you were joking that the smell would kill her.’

‘The other day I didn't know we would cut back on the blue in the tapestries. If I don't get that blue soon we'll run late already and be fined by Léon. Jacques knows that. He has me by the balls.’

I thought of Aliénor's shudders in the Chapelle. ‘She detests him.’

‘Christine, you know this is the best offer Aliénor will get. She's lucky to have it. Jacques will look after her. He's not a bad man, apart from the smell, and she'll get used to that. Some people complain of the smell of the wool here, but we don't notice it, do we?’

‘Her nose is more sensitive than ours.’

Georges shrugged.

‘Jacques will beat her,’ I said.

‘Not if she obeys him.’

I snorted.

‘Come, Christine, you're a practical woman. More so than me most of the time.’

I thought of Jacques Le Bœuf chomping his way through half of our pie, and of his threat to ruin Georges' business. How could Georges agree to such a man for his daughter? Even as I thought it, though, I knew there was little I could say. I knew my husband, and he had already decided. ‘We can't spare her now,’ I said. ‘We need her to sew on these tapestries. Besides, I've made nothing for her trousseau.’

‘She won't go yet, but she could when the tapestries are almost done. You could finish the sewing on the last two. By the end of next year, let us say. She could certainly be at Jacques' by that Christmas.’

We stood silent and looked at the dog roses growing along the trellis. A bee was worrying one, making its head bob up and down.

‘She must know nothing about this for the moment,’ I said at last. ‘You make it clear to Jacques that he can't go about bragging of his wife-to-be. If he says a word the betrothal is broken.’

Georges nodded.

Perhaps that was cruel of me. Perhaps Aliénor should be told now. But I couldn't bear to live with her sad face for the next year and a half while she waited for what she dreaded. Best for everyone if she knew only when it was time.

We walked back through Aliénor's garden, which was bright with flowers, tangles of peas, neat rows of lettuce, clipped bushes of thyme and rosemary and lavender, of mint and lemon balm. Who will look after this when she's gone? I thought.

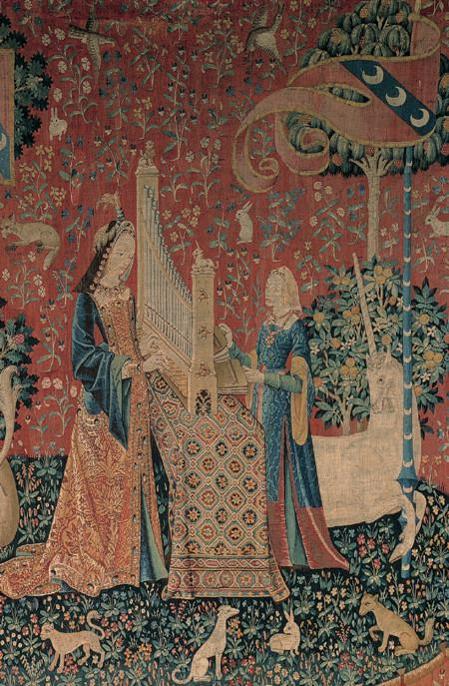

‘Philippe, stop your painting now — I need you to draw on the warp once we've put the cartoon underneath,’ Georges said, stepping ahead of me. He went up to Sound. ‘

Tiens

, help me take this inside, if it's dry. Georges, Luc!’ he called. He sounded stern and brisk — Georges' way of leaving behind our talk.

Philippe dropped his brush into a pot of water. The boys hurried out from the workshop. Georges Le Jeune climbed up a ladder to detach the cartoon from the wall. Then, one man at each corner, they carried it inside to the loom.

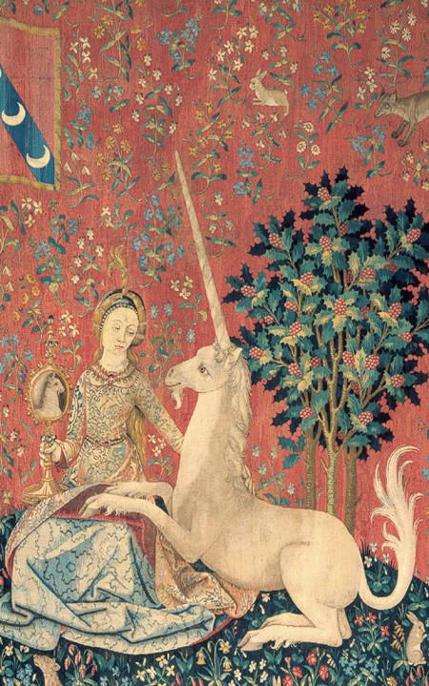

With the cartoon gone the garden suddenly felt empty. Nicolas and I were alone. He was painting the Lady's hands now as she held a carnation. In his own hand he too held one. He did not turn around but kept his back to me. That's unlike Nicolas — he doesn't usually give up the chance to talk to a woman alone, even if she is older and married.

He was holding his back and head very stiff and straight — from anger, I realized after a moment. I gazed at the white carnation between his fingers. Aliénor grew them near the roses. He must have come over to pick one while Georges and I were back there talking.

‘Don't think badly of us,’ I said softly to his back. ‘It will be best for her.’

Nicolas didn't answer immediately, but held his brush up to the cloth. He did not paint but remained with his hand suspended in the air. ‘Brussels is beginning to bore me,’ he said. ‘Its ways are too boorish for me. I'll be glad to leave. The sooner the better.’ He glanced at the carnation he held, then threw it down and crushed it under his heel.

That evening he painted until very late. These summer nights it is light almost to Compline.

‘Chevalier's gift is not limited to undercover education and the creation of lively characters. What she does best is to study a famous work of art with the eyes of a bright, inquisitive child, teasing out a story that might lie behind it. The marvellously enigmatic medieval tapestries of her title are a gift to this, her own brand of historical fiction.’

Independent on Sunday

‘Chevalier sets her imagination free to create a story peopled by the artists, weavers and the women whose likenesses appear in the tapestry … an engaging and enjoyable read.’

Daily Mail

‘Cartoonists, weavers, dyers, financiers, even those who trim the hem, all add a dash of their own desires to the mix. Thus when the tapestry is unrolled there shimmers beneath its brilliant surface another shadowy net of threads, weaving together the loves and longings of all involved …

The Lady and the Unicorn

will perhaps eclipse

Girl With a Pearl Earing

… Her characters are not tossed about by large well-documented events; it is the machinations of their inner worlds that make the story and then drive the plot. Yet there is no doubt that the past is a beautiful and somehow apt surround for her tales of human nature, in much the same way that antique settings can add a golden gloss to jewels.’

Guardian

‘A beautifully written tale, I could not put it down … an exquisite, moving and convincing story, drawing realistic and rounded characters who each tell their aspect of the tale … This is not just a novel about the creation of a work of art, but a tale of ambition, lust, betrayal and heartbreak … a compelling and enormously enjoyable work.’

Evening Standard

‘The strongest scenes in Tracy Chevalier's charming novel concern the lives of the craftsmen in late 15th-century Brussels weaving the tapestries … the novel neatly presents a weave of first-person narrative voices, each speaker creating a new strip of plot … Nicolas functions as a sort of running stitch, tying the various stories together, looping back and forth between Paris and Belgium, one woman and another. Eventually, he himself is caught, and stitched in to a woman's design.’

Other books

Taken by Storm: A Raised by Wolves Novel by Barnes, Jennifer Lynn

The Word of a Liar by Beauchamp, Sally

Trumpet on the Land by Terry C. Johnston

Arctic Summer by Damon Galgut

Miriam's Well by Lois Ruby

Swordmistress of Chaos by Robert Holdstock, Angus Wells

The Carnelian Legacy by Cheryl Koevoet

Leashed (Going to the Dogs) by Dawson, Zoe

High-Caliber Concealer by Bethany Maines