The King's Speech (13 page)

Authors: Mark Logue,Peter Conradi

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Royalty

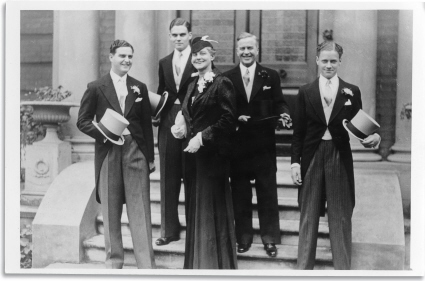

The Logue family dressed up in morning suits for Laurie’s wedding day, in July 1936, on the steps of Beechgrove

Left to right: Laurie, Valentine, Myrtle, Lionel, Antony

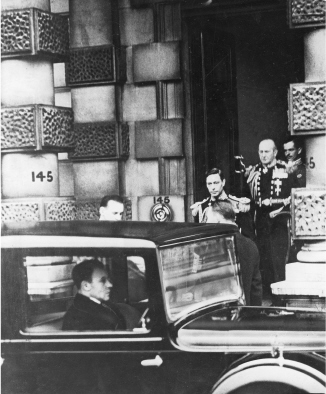

The Duke leaving 145 Piccadilly on his way to St James’s Palace to take the Oath of Accession after the abdication of his brother, King Edward, 12 December 1936

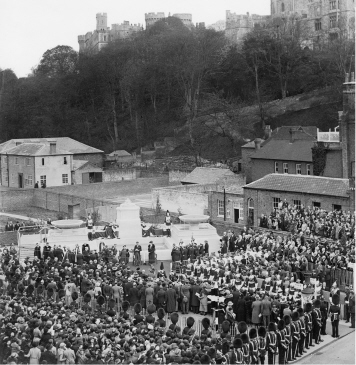

King George VI’s first speech in public since his accession four months earlier, at the unveiling of the George V Memorial at Windsor on 23 April 1937

Lionel in his office at 146 Harley Street, with a portrait of Myrtle on his desk

Myrtle in her Coronation gown

George VI’s coronation on 12 May 1937. Logue and Myrtle are seated on the balcony above the Royal Box at Westminster Abbey

In the months that followed, the British newspapers increasingly carried articles commenting on the progress that the Duke was making – all of which were collected by Logue and pasted into a large green scrap book that has passed down the family.

Reporting on the Duke’s attendance at a fundraising banquet at the Mansion House in London for the Queen’s Hospital for Children, the

Standard

noted on 12 June 1928, ‘The Duke has vastly improved as a speaker and his hesitation has almost entirely gone. His plea for the children showed real eloquence.’ A writer from the

North-Eastern Daily Gazette

came to the same conclusion the following month after a speech by the Duke at another fundraising event for the hospital, this time at the Savoy. ‘Taking it all round, I am not sure that his speeches do not equal those made by the Prince of Wales,’ the newspaper commented. ‘And that is a pretty high standard. The Duke has learnt the speaker’s two most valuable lessons – wittiness and brevity. He used rather a good simile at this dinner when he said that he hoped the speakers who followed him would have the effect of the electric plucker he recently saw at an agricultural show – an apparatus which divested a chicken of its external possessions in next to no time.’

The

Evening News

took up the same theme that October. ‘The Duke of York grows in fluency as a speaker,’ it noted. ‘He is markedly more confident than he was two years ago, more confident, indeed, than he was a few months ago. Continued practice tells in public speaking.’ The

Daily Sketch

was impressed that the Duke was ‘freeing himself more and more from the impediment that formerly interfered with an appreciation of the true gift he possesses for the apt and finished phrase’. Hearing the ‘music’ in the Duke’s voice during a speech at the Stationers’ Hall, a somewhat more imaginative writer for the

Yorkshire Evening News

was reminded of other examples of great orators who had overcome hardships. ‘I thought of Demosthenes and the story of his victory over hesitant lips; of Mr Churchill and his conquest; of Mr Disraeli whose maiden speech was a humiliation; of Mr Clynes, who in his teens, used to go out into a quarry to practise the art of speaking.’

50

While newspaper writers noticed the improvement in the Duke’s speaking, quite how he had managed to achieve it (and the special role played by Logue) remained a mystery to those who heard him speak, to the wry amusement of his teacher. In another cutting from the period headed ‘How well the Duke of York has trained himself to speak’, Logue has underlined the phrase ‘has trained himself ’. In a short report on 28 November 1928, the

Star

attributed the Duke’s overcoming of his ‘old difficulty in speaking’ to the influence of his equerry, Commander Louis Greig, who had become a close friend since they first met almost two decades earlier when Greig was assistant medical officer at Osborne naval college.

Yet it was only going to be a matter of time before the secret got out, given the number of visits the Duke was making to Harley Street and the frequency of Logue’s appearances at his side. On 2 October 1928 Logue received a letter at his practice from Kendall Foss, a correspondent in the London office of the United Press Associations of America news agency.

‘Dear Sir,’ wrote Foss from the agency’s office in Temple Ave, EC4.

I understand that you are in possession of the facts concerning the curing of the Duke of York’s speech impediment.

Although some miscellaneous information on this subject is current in Fleet Street, I should naturally, like to have the truth before printing this story.

Out of deference for His Royal Highness, I am writing to you for an appointment, hoping that you will be good enough to supply us with the facts for an exclusive story to be published in North America.

Trusting to hear from you favourably, I remain,

Kendall Foss for the United Press.

Logue appears to have rung Hodgson for advice but was told he was ‘on holiday, and lost on the Continent’. Foss followed up over the next few days with phone calls both to Harley Street and Bolton Gardens. On 10 October an exasperated Logue wrote back: ‘While thanking you for your courteous letter of the 2nd October, it is quite impossible for me to give any information on the subject.’

Undaunted, Foss pressed on with his researches. His story eventually appeared on 1 December 1928 on the front page of the

Pittsburgh Press

and in a number of other US papers. ‘The Duke of York is the happiest man in the British Empire,’ it began. ‘He no longer stutters . . . The secret of the duke’s speech defect has been well kept. Since boyhood he has been troubled and for about two years he has been undergoing a cure which has proved successful. Yet the story has never been published in Great Britain.’ The account that followed had, Foss wrote, been ‘only obtained after the most exhaustive inquiries and investigations. Almost no one in Great Britain seemed able to provide information’.

Foss went on to tell the story of Logue, his techniques and how he had come to work for the Duke. He also noted how in the past, when the royal couple entered a room, the Duchess would step forward and do the talking to save her husband the embarrassment of a stumble. Now, by contrast, he said, ‘she hangs back, shyly watching the man of whom she is obviously proud’.

Logue was quoted as merely confirming the Duke was his patient, saying that professional etiquette prevented him from telling more. The Duke’s private secretary was equally unwilling to elaborate.

Such reticence did not dampen the journalist’s praise for Logue’s work. ‘Obviously, Logue’s analysis of the Duke of York’s difficulty was the correct one,’ Foss concluded. ‘Those who had never heard the Duke speak until recently said they would never dream that he had once suffered agonies of embarrassment over his speech. Much like Demosthenes in ancient Athens, the Duke has mastered a handicap and is making himself into an accomplished orator.’

The floodgates were now open. The following day Gordon’s newspaper, the

Sunday Express

, weighed in with its own version – which then went round the world. ‘Thousands of people who have heard the Duke of York deliver public speeches recently have commented on the remarkable change in his speech-making,’ the newspaper wrote. ‘The

Sunday Express

is able today to reveal the interesting secret behind it.’ The story went on to cover much the same ground as Foss’s, noting how what had started as a slight stammer turned into a defect that ‘spread its shadow over the whole of the Duke’s life’, leaving him literally lost for words when he met strangers, with the result that he began avoiding speaking to people.

Despite the closeness of his friendship with Gordon, Logue did not allow himself to be any more forthcoming about his role than he had been with Foss. ‘Obviously, I cannot discuss the case of the Duke of York or any other patients of mine,’ he told the newspaper. ‘I have been asked about this matter many times during the past year by both British and American newspapers and all I can say is that it is very interesting.’ The

Sunday Express

’s story was reprinted or followed up by newspapers not only in Britain but also elsewhere in Europe – and especially in Australia, where Logue’s contribution was noted with understandable pride.