The Kills: Sutler, the Massive, the Kill, and the Hit (106 page)

Read The Kills: Sutler, the Massive, the Kill, and the Hit Online

Authors: Richard House

This situation sustained itself for a while. Once the apartments were looted it seemed that there could be little else that could be taken. And perhaps this might have been the case, perhaps this might have been the story if the women in the courtyard had not caused another upset.

(page 43)

The young private, the youth from Kentucky, was found stabbed. The wounded man wandered, trance-like, out of the lower rooms, into the courtyard. He walked through the stairwells, vacant, seeming to have some quiet purpose, stepping as a cat through wet grass, lifting up his feet, but not sensate enough to express exactly what it was that he was doing, what it was that he wanted. His hands, slashed, showed defensive wounds, where, perhaps, he had tried to grab the knife. His handprints along the wall, small slides and smudges tracking his progress from floor to floor. We saw the blood, ignored it, then later, more worried about what fresh trouble this would bring, my brother and my father followed the trail up to the top floor.

They found him sweating and panting. In the darkness his tunic appeared black, the blood having seeped through his jacket.

Unwilling to touch him, they raised the alarm. One dead solder would be no end of trouble and they did not want to be involved, but considered quickly – which would be worse? To allow him to die and suffer whatever consequences the Americans would bring down on us, or perhaps, through intervening, be seen as people who had helped, at the same time appear as collaborators to our own.

My father could not make the choice. My brother, independently, sounded the alarm. Went down to the basement and roused the women, got the soldiers away from their women’s arms and beds and brought them up the stairs to their companion, who now lay in a swoon.

They brought him down in a blanket, a makeshift stretcher, and laid him in the courtyard, still alive, but feeble from blood loss. The women came out, one by one, and held back to the courtyard walls, hands to mouths, frightened, recognizing that this would be no good thing. Ten of us could die, twenty, a hundred, and it would mean nothing. But one wounded American signalled a whole world of trouble.

The soldiers themselves appeared stunned. They stripped off the boy’s tunic, demanded water and rags and found him stabbed once in the side, and once in the chest. The boy lay pale, his wounds agape. His chest raising and falling with laboured breaths.

The military police arrived alongside an ambulance, and the boy was dressed and taken away with some hurry, and greater fears that he would die. The courtyard trapped silence, no one dared speak, and it seemed that all, even the men who had spent the night here, were under suspicion.

(page 45)

Let me describe now what was happening inside our apartment. How this event brought down a deeper distress. My mother at the table, too gone to wail, head in hands, believing that this would be the last that we would see of my brother. My father, useless, did not know what to do with himself and hung, waif-like at the door. My sister kept back, and I urged her to pack. We would hide her in one of the other apartments. They would not find her. We would say that she had already gone, that she was working elsewhere, that she was now in a city in the north, and that we had not heard from her. We could say that she had died. We would take her belongings, all evidence of her and deny that she existed, say that their records were incorrect, that there never was a girl here, that we had no sister, there was no daughter. The Americans would be bound to come and question us now. Our involvement would be examined. This attention would need to be managed if we did not want it to cause us trouble. Looking about the room, about the apartment, as bare as it was, it would not take much to convince them that there was no girl.

We hid her in another apartment, the room a chaos of broken furniture – it was not hard. She dug herself under the broken frame of a bed and slipped from view.

The Americans came in the night. They brought dogs. And now my mother’s grief grew into song. She shrieked as they came into the courtyard as they broke the doors and rounded up the women, hauled them into trucks. I strained to watch but did not see L— but watched as the women were roughly gathered, bound, thrown onto the back of the vehicle like meat. They took them away and left a team of men to clear the room, who threw out the beds, tossed the clothes into the courtyard, and then set fire to it; sparks rose and sucked the air, a column of smoke billowed upward. They threw linens, bedding, mattresses, clothes and shoes onto the fire, not caring that this might spread, that the dry night air would carry sparks into other homes.

I saw the face of my neighbours at the windows, brightened by firelight, who each caught my eye, and each turned away, slipped back into the darkness, wanting not to be seen. The dogs howled at the fire, strained at their leashes, and here – finally – we come to the worst.

One of these hounds released by its minder hurtled up the stairs, and found its way floor by floor to the vacant apartment in which we had secured my sister, it sought out the chaotic heap under which she lay and began to bark and howl and scrambled at the furniture.

They found her, the soldiers. Brought her out. Took her away.

(page 47)

My mother returned to the new ministry and came back exhausted, used up. They would not speak with her. Threatened her with arrest when she started to make a fuss. She begged, fell to her knees, offered herself in her daughter’s place. Attempted to explain that they had taken her by mistake, that she was not one of the women they had herded in the palazzo. She was a girl. Her daughter. Surely they had daughters themselves? Surely they had mothers also, who they would not bear to see degrade themselves? Could they not see that this was a simple mistake. She would make no complaint. She would be grateful. She would spy for them, inform on the neighbours, collect information. She would do anything if they would release her child. She is fourteen. Return her to me.

The man she spoke to appeared not to understand. Refused to listen, and when he had to, sat without expression, a wall. Stones would have wept, she said, but this man saw nothing in front of him, nothing recognizable, nothing from which he could draw the simplest strand of sympathy.

Outside the building she was met by a woman, an American who hurried after her. This girl, she said, had heard her, understood her, and realizing that the adjutant would do nothing, explained with care that there was a magistrate. One of our own people, and that my mother should assemble witnesses, set out a record of what had happened and have this signed by neighbours. The magistrate would not ignore us, with evidence he could over-step the adjutant and speak directly with the military commanders. There was hope in this, a little hope.

On her return my mother explained what we needed to do. Using D.P.’s paper I addressed the facts of the night before. Wrote first our address and date as I had seen on official documents, set out the names of the people in the house, wrote my sister’s name in capitals. After this we knocked on our neighbours’ doors. If they had refused my mother, they could not refuse the testimony of others. There were men who had witnessed this. Neighbours drawn to their windows and balconies – she had seen them, I had seen them – keeping safe behind shutters, but watching; she had felt them, seen them, knew they were there.

Some, at first, admitted as much. Gave their condolences. Shook their heads in horror. That it would come to this. After everything. Daughters taken, stolen from their houses. Floor by floor we knocked on each of the doors, implored each neighbour the same. Come with us. Come to the magistrate, help present our case, prove that our daughter existed, and that she was taken from us. Sign here. A piece of paper, give some testimony, if not your name then a mark, a simple mark. None of them. Not one. Would sign.

Misfortune is a river, and once it has found its course it will widen its banks, flood wasteland, vineyards and farmland without discrimination, swamp and lay the plains to waste. The same day my sister was taken, the British stood by as the museums were looted. Done with our homes, our palaces and museums were now the target.

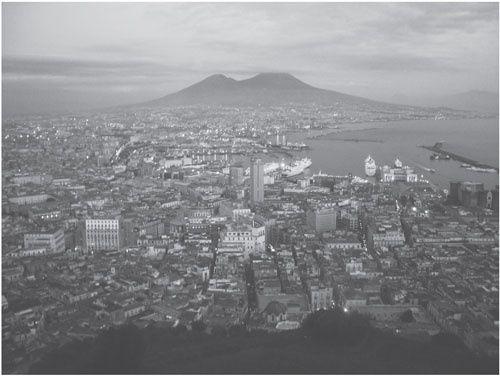

We determined to see the magistrate without the petition. If he were one of our countrymen he would surely help us. The streets, which by mid-afternoon would normally be quiet, were hectic with activity. Troops, American and British, lined the boulevards, the shops along the main thoroughfares were shuttered, the ministry itself closed. Police blockaded the main arcade, at the port the ships’ guns faced inland. It became clear, as we ran from corner to corner, inching our way to the magistrate’s court, that there were fears of an insurrection. By the time we passed the National Museum the looting was done. The doors lay open, and a white thread of smoke blew from the back of the building. There were shards, glass from the windows, stones used to pelt the doors, and papers scattered across the pavement and into the road. Tanks faced the building and the men now guarding (surely too late) wore visors and masks so their faces could not be seen.

The magistrate was not at the court, as we should have expected. Instead, at the height of the looting, the Americans had driven him to the museum, and there was no clear idea what had then happened to him, except that he had failed to quell the trouble.

We waited at his office. His secretary sat behind a desk and told us that it would do no good. ‘There will be no other business now. They (meaning the Americans, perhaps the British) were working hand in hand with the looters. These weren’t bandits. This was organized, carefully planned. Much of what they wanted, the prize of our culture was gone already by the time they arrived. The people they caught were passers-by. They will be shot. Under martial law. They will be shot.’

He knew nothing of our sister. Nothing about the women at the palazzo. Nothing about the entertainments, and did not seem surprised by the news. ‘A car we could find,’ he said, ‘we know the names of every thief. A person.’ He shrugged. ‘They disappear. If someone is gone. I am sorry to report. They are gone.’

His office, decorated white and blue, held busts. Heads of state, former kings, and in the corridor also I noticed the bronze likenesses of our philosophers, a great deal of statuary in fact along the corridors and stairwells, none of it particularly fitting the surroundings. Watching me the magistrate’s clerk said that we should go. There was nothing he could do, and nothing either that the magistrate could manage. Without verification of our claim we had no grounds to make a petition.

(page 50)

My sister returned two days later at sunset as we returned, again, from the magistrate’s office. ( . . . )

I called on Dr P—, begged him to come see her, to help. Knocked hard at his door. Saw that his blinds were slightly opened. Called to him. Insisted that I knew he was in. That I would break the door. His voice, feeble but clear, refused to assist, and told me, directly, and with some shame to go away.

I ran to other doors, to other neighbours and asked for water, for towels, for a trough so we could bathe her. Door after door remained unanswered. About the palazzo hung a thick silence. The silence of people hiding, of people holding their breaths, of people closing their eyes and hardening themselves, making themselves as dull as walls and floors and stone. Not one person came to our aid.

(page 51)

The morning after the return of my sister, my brother took himself to the vineyard and used a curved pruning knife to slit the artery in his leg. He lay with his back to the vine and bled himself of life. He left no note or explanation, which did not need to be voiced perhaps. I found him, and held him at the end. I sat with him long after, and thought hard over the facts and realized that everything I had done to this point was driven by coincidence. The opportunities opened to me had come through chance alone. The misfortunes were otherwise, and were driven by situations which I believed I could not control. But now, it seemed to me that I could be less undirected. Less blown. More determined. If I did not I would end up used like my brother and sister. Here, as if to give example to the trouble which I debated, I was found with the knife, covered in blood, and arrested.

And so I was imprisoned for the murder of my brother.

Yee Jan waited in the cubicle until he could be certain that the students were gone. Some stuck around for extra sessions, one-on-ones that lasted an hour at most. Others dawdled to chat and wrap up the day, and took too long to say goodbye. Tonight they were filming at the marina and Yee Jan didn’t have time to dawdle.

They

meaning a film crew, technicians, handlers, movers, a mix of lean and professional Americans and Italians (men) from Los Angeles and Rome: people (men) so serious and focused and so used to crowds they saw nothing but the job ahead of them. Yee Jan wanted to watch them for their industry alone. The crew wore military green T-shirts and vests with

The Kill

printed in white script on the front and the outline of a white star in a white circle on the back. He wanted one of the vests, although he was happy to settle for a photograph. Yee Jan leaned into the mirror and considered how this could be achieved. He pinched his eyelashes to tease out stray hairs. He’d come in early that morning specifically to watch the maintenance crew off-load lights from flat-bed trucks and prepare the cabins (technically trailers) and set them end on end on the broad sidewalk that ran alongside the port, and just as soon as he was ready he’d go back and find them.