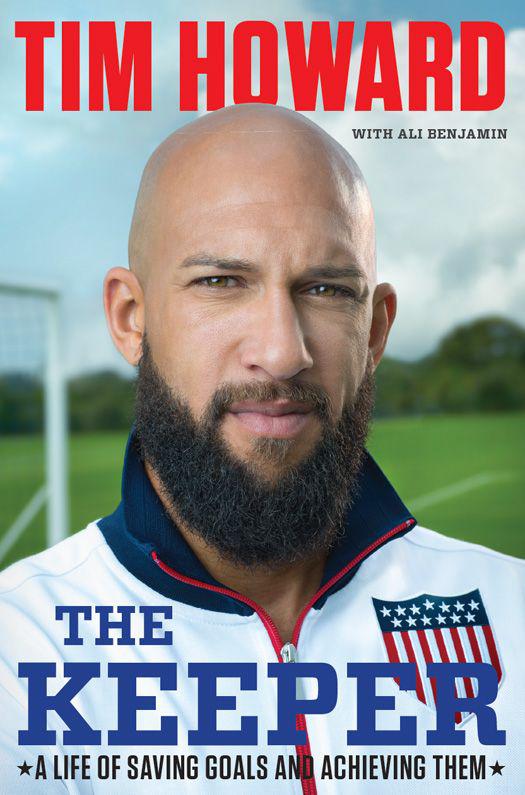

The Keeper: A Life of Saving Goals and Achieving Them

Read The Keeper: A Life of Saving Goals and Achieving Them Online

Authors: Tim Howard

For my mom, who gave me everything

And for Alivia and Jacob, who are my everything

In New Jersey, Anything Is Possible

“It Will Take a Nation of Millions to Hold Me Back”

USA vs. Belgium: Warning Shots

“You’re Not in America Anymore, Son”

USA vs. Belgium: Nothing Gets Through

T

he game I play has a different name in the U.S. than it does in the rest of the world, and I’m one of the few people who uses both. When I’m playing for my club team, Everton, in Liverpool, England, I refer to the sport as football, but when I’m playing for the U.S. National Team, I call the sport soccer. In this book, I have decided to go with the latter.

ONE

USA VS. BELGIUM: PREGAME

ARENA FONTE NOVA

SALVADOR, BRAZIL

JULY 1, 2014

E

ven from the locker room, I can hear the rumbling of the crowd. The drumbeats. The chants: USA! USA!

I believe that we will win.

I spent the past 24 hours doing what I always do: I stuck to my routine and stayed focused. Just as I’ve done today, warming up.

I started, as usual, by getting dressed in the same order—right leg before left for shin guards, socks, and shoes. Then I taped my fingers in precisely the same pattern I always follow. On the field, I checked the orange cones, right to left, with my feet, moving the one that my goalkeeping coach leaves off center deliberately so I can realign it.

This whole process might seem crazy to everyone else, but to me, nothing makes more sense. It’s the only way I know to feel calm and in control.

It’s the routine I’ve had since my first game at Everton, when

I finally had the experience and conviction to take control of my own preparation. Eight years and 500 games later, it still works—it puts my head in the right place, a place that tells me I can handle whatever comes my way.

I can’t know what’s coming. I only know how to make myself feel ready for it.

A few feet from where I’m standing now in the locker room, Michael Bradley looks intently at our center-back Matt Besler.

When they put Lukaku in

, Michael says, his voice measured, assured,

you’ve got to close him down alright?

Michael moves on to DaMarcus Beasley, our left fullback.

When Mirallas comes on, you can’t let him get behind you.

Jürgen Klinsmann moves through the locker room clapping players on the back. He’s upbeat as he makes the rounds. He speaks to Julian Green, quietly, in German. Whatever he says, Julian smiles.

Nearby, Clint Dempsey pulls his yellow captain’s armband over his bicep. His hardened jawline, his steely eyes tell me all I need to know: it’s on.

There’s a poster on the wall of the locker room, a close-up image of a bald eagle, staring straight ahead. The words next to it:

ONE NATION, ONE TEAM.

Something is in the air. I can feel it. Actually, I’ve been feeling it since we arrived in this country, every time I spotted an American flag next to a Brazilian one on a clothesline, every time I heard strangers shouting to us, “I believe!”

I believe that we will win.

I believe that we have everything we need this time.

We are strong. We have speed and power and grit. The fight is in us.

We’ve been beating powerhouse countries for over a decade.

We’ve earned a spot as the top team in our region; we’ve even beaten Mexico on their home turf for the first time in history.

We’ve beaten Spain in the Confederations Cup, making us the first team in 36 games to conquer the defending European champions. We’ve surprised the soccer world again and again and again.

Last night, Michael Bradley looked me straight in the eye and said the thing that everyone seems to be feeling, but which they haven’t yet dared to say out loud: “I really think we can beat Belgium. I think we can get to the quarterfinals.”

I believe that we will win.

Dempsey calls us over.

Let’s get this done for our country, okay?

We’re pumped now.

Anyone else have something to say? Tim?

No. I’ve said it all. Marked up the white tactics board and tapped it again and again, reminding our defenders of our strategy.

Dempsey locks eyes with me, then says to the group,

Let’s bring it in on three.

We place our hands in a circle. Dempsey counts, and we respond in unison.

USA!

We walk out of the locker room. In the hallway, I see the two Belgian players who also happen to be my Everton mates: Kevin Mirallas and Romelu Lukaku. We hug, but we all feel the tension; we’re not teammates today. We’re opponents.

Belgium’s starters line up; we fall into place beside them, our eyes fixed straight ahead. Nearby, children wait, ready to take our hands.

The referee stands between us, holding the ball.

That ball: I ask the ref if I can hold it. Another ritual. I turn it over in my hands, feeling its curve against my keeper’s gloves.

Then I make the sign of the cross.

Michael bellows, “Come on, boys.”

Almost there.

That’s when I say the same prayer I always do before a game, the one for my children: I pray that they’ll know how much I love them, that they’ll be protected from harm. This is the prayer that grounds me, that puts everything in perspective.

We walk out of the tunnel, and the stadium erupts.

It’s all color and light and sound. The green of the field, the ref’s neon jersey, the blue stands that surround us. Flags and scarves and banners everywhere, in red, white, and blue. The thunderous roar of that crowd.

When I reach the field, it’s time to bend down and touch the grass; then the sign of the cross, again. Two more rituals.

I believe that we will win.

Somewhere in that roaring crowd sits my mom. Simply knowing she’s there gives me the old feeling I had as a kid playing rec league soccer, when she’d move closer to me during a tough moment, lending me strength—telegraphing the message, simply by her presence:

You’ll be okay, Tim.

I know others are watching back in the States. My old coach. My dad. My kids. My brother. Laura.

And so many more. Nearly 25 million people in the U.S. watched our last game against Portugal—50 percent more than had tuned in to either the World Series or the NBA Finals. At this very moment, people are crowded into public spaces all over the U.S., watching together. Twenty-eight thousand in Chicago’s

Soldier Field. Twenty thousand in Dallas. Ten thousand in the small city of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

They’re out there right now, wearing Uncle Sam hats, stars-and-stripes T-shirts, their faces painted red, white, and blue. They’re out there for us. They believe in us.

I believe that we will win.

When the whistle blows, I cross myself for the third time. The final ritual.

We can do this. I am certain of it. We can win today. And if we do, if we advance to the quarterfinals, it will be the greatest thing I’ve ever done for my country.

This is going to be the game of my life.

A

ll my saves are rooted in New Jersey—every leap, every block, every kick and dive and fingertip touch. All of them were born in Jersey.

I spent my childhood following my older brother, Chris, around Northwood Estates, our apartment complex in North Brunswick. While “Northwood Estates” might conjure images of rolling hills and English gardens, the reality was far more modest: a group of functional brick buildings, with 250 units in all, wedged between Routes 1 and 130. We were the far outer edge of the suburbs, a stone’s throw from a pizza shop and not much else.

A few miles away were the manicured streets of the Fox Hill Run development, where some friends of mine lived. I was always taken aback by the upper-middle-class luxury of their homes: high ceilings and white carpets and light streaming in through skylights. They had pool tables in finished basements, huge backyards with pools and hexagonal gazebos where their parents sat sipping glasses of wine.

If you could make it to Fox Hill Run

, I thought,

you really had it made

. But if Jersey gave me anything,

it gave me perspective. A few miles in the other direction lay a rough apartment complex with a reputation for gang violence and corner crack deals.

In our New Jersey, we heard a medley of languages—Spanish, Polish, Punjabi, Italian, Hebrew. Leaving our apartment each day, we were often hit with a pungent and mysterious odor; it took years before my brother and I figured out that it was the smell of curry bubbling, the nightly fare for a Sikh family who lived in an adjoining building. One of the kids in that family, Jagjit, rode his bike with us, occasionally stopping to adjust his turban.

In that eclectic, multinational mix, I fit right in.

My own father, who moved out before I formed my first memory, is black, a Woodstock hippie turned long-haul trucker. My mother is white, born in Hungary to a teacher and a former POW. Although deeply shy with others, Mom was always affectionate and loving with me and Chris.

The world around me was so diverse, so filled with different ethnicities and experiences that I never bothered to wonder about my own skin until I was ten years old.

“Why does your skin have that dark color?” a white classmate asked one afternoon.

I looked at my arm and considered his question. My skin

was

pretty dark, now that he mentioned it. I shrugged.

“My family went to Florida,” I said. It was true. We had been to Florida . . . about 20 weeks earlier. “I guess I still have a tan.”