The Judgment of Paris (37 page)

Worse news was still to come for Monet as he fell afoul of his family as well as the Salon jury. Camille was with child, an unplanned and (for Monet at least) an unwanted pregnancy. Early in April, soon after learning of his rejection, Monet returned to Le Havre to confess to his father the full details of their relationship, and also, no doubt, to solicit financial assistance. Adolphe Monet was not amused. In a letter to Frédéric Bazille the elder Monet fumed that his son had taken "the wrong path" (a strange echo of Breton's objection) and needed to mend his ways if he hoped to remain in the good graces of his family.

9

He therefore ordered Claude to quit Paris and move to his aunt's house at Sainte-Adresse in Normandy.

But Monet, for the time being at least, did not wish to abandon either his pregnant mistress or the recreations of Paris. Instead, he obtained permission to set up his easel on a balcony of the Louvre, from where he painted

Garden of the Princess,

a cityscape with the Pantheon rising in the background. He sold the work to a dealer named Louis Latouche, who promptly placed it in the window of his small shop in the Rue Laffitte. Here it attracted the attention of passersby, among them Honoré Daumier, a lithographer and political satirist who urged Latouche to remove such a "horror" from his window.

Garden of the Princess

also drew the adverse attentions of another artist. Édouard Manet likewise stopped in the street and, according to legend, remarked disdainfully to a group of his friends: "Just look at this young man who attempts to do

plein-air.

As if the ancients had ever thought of such a thing!"

10

Despite his flirtations

-with plein-air

painting at Longchamp and Boulogne, Manet apparently still believed that great art could only be produced in a studio, not under the open skies.

The stringency of the 1867 jury meant that, as usual, demand escalated for another Salon des Refusés. In early April the Comte de Nieuwerkerke received an anonymous letter purporting to come from a group of artists who stated, in threatening tones: "This injustice is revolting, and you had better believe that it's not a favor we're demanding, it's our right and we hope you will grant it."

11

Agitations by bands of rejected artists soon grew so heated in the vicinity of the Palais des Champs-Élysées that complaints against them were registered with the Prefect of Police.

12

A more considered protest came from Frédéric Bazille, who sent Nieuwerkerke a letter requesting the opportunity for the

refusés

to exhibit their work in a separate Salon. "Knowing your benevolent solicitude for our interests," Bazille finished, somewhat sarcastically, "we are hoping that you will be willing to take our request into consideration."

13

Attached was a five-page list of signatories that included Manet, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Daubigny. In the middle of April, when Bazille's petition bore no fruit, yet another letter featuring many of the same signatures landed on Nieuwerkerke's desk. At this point the beleaguered Superintendent of Fine Arts agreed to meet representatives of the disgruntled artists, though in the end he denied their requests for another Salon des Refusés. He had little enthusiasm for risking a repeat of the undignified events of 1863 at a time when the eyes of the world were fixed on Paris.

At the time of the petitions against the jury's decisions, Nieuwerkerke was busy curating not only the Salon and the International Exhibition of Fine Arts but also a retrospective of the works of Ingres, who had died three months earlier at the age of eighty-seven. The Superintendent could take great satisfaction in the fact that the exhibition of 600 of Ingres's paintings and drawings was a tremendous success, with more than 40,000 people filing into the École des Beaux-Arts to see masterpieces such as

The Apotheosis of Homer, The Vow of Louis XIII

'and

Jupiter and Thetis.

Meanwhile, on the opposite bank of the Seine from the École, the exhibitions of Manet and Courbet were meeting with a quite different reception.

The poor weather that hampered the opening of the Universal Exposition likewise played havoc with Manet's plans for his one-man show. He had been hoping to open the doors of his pavilion on the first of April, but work had barely started on the project by that date as he found himself mired in both the mud of the Place de l'Alma and—much worse—unpleasant legal wrangles with his builders.

For the design of his thirty-foot-long wooden pavilion Manet had employed an architect recommended by the Marquis de Pomereu-d'Aligre. After drawing up a set of plans, the architect had entrusted the work to a contractor named Letellier, who subcontracted the work to another builder and promptly vanished. The subcontractor worked sporadically through the bad weather of February and March before downing tools altogether at the beginning of April with the job nowhere near complete. Having paid out a total of 18,305 francs, Manet was furious. Time was obviously of the essence since he needed to have his paintings exhibited in time to catch the attention of the millions of people pouring into Paris for the Universal Exposition. He therefore brought legal pressure to bear on the wayward contractor by engaging a solicitor named Chéramy. Légal summonses were promptly served on Letellier and a man named Belloir, the housepainter in charge of decorating the pavilion. The truant laborers arrived back on the site, where work finally resumed soon after the Salon opened in the middle of April.

14

Manet was also involved at this time in more solemn and heartrending affairs. By 1867 Baudelaire was back in Paris, in a special hydrotherapy clinic near the Arc de Triomphe, following a series of strokes and seizures caused by advanced syphilis. Newspapers in Paris had reported his death a year earlier, in April 1866, after he suffered a debilitating stroke in Belgium. While the obituaries had been premature, the poet was in an extremely serious condition, paralyzed down his right side and virtually incapable of speech. His mother had brought him back to Paris in July, and Manet had paid frequent visits to the clinic, where to ease Baudelaire's sufferings Suzanne played excerpts from

Tannhauser,

his favorite piece of music. Throughout the last half of 1866 and the early months of 1867, the garden in the hydrotherapy clinic became a place of pilgrimage for artists and writers such as Nadar, Gautier, Champfleury and the poet Théodore de Banville, all of whom gathered around the disabled Baudelaire. But it was Manet, apparently, whom the poet most wished to see. At the end of 1866 the painter received a letter from Nadar describing how he had discovered Baudelaire in the garden crying: "Manet! Manet!"

15

These various anxieties kept Manet from his painting. At some point in the spring of 1867, however, he took a canvas and easel to the hill of the Trocadéro, a quarter mile downstream from where his star-crossed pavilion was taking shape near the Pont de l'Alma. Though used as a refuse dump during the Universal Exposition, the Trocadéro provided a beautiful panorama of the Palais du Champ-de-Mars. Therefore, despite his supposed reservations about

plein-air

painting, Manet began a cityscape not unlike Monet's

Garden of the Princess.

He placed a series of figures in the foreground—a clutch of men in top hats, others in military uniform, and a group of ladies wielding their ubiquitous parasols. He also added the fifteen-year-old Léon Koella, spiffily attired in a pearl-gray top hat and white trousers, walking a shaggy-looking dog along the path. Kranz's gigantic exhibition hall was shown at a distance, obscured by clouds of steam, while Nadar's

Cileste, a

small teardrop, hung in the sky above.

Had Manet's panorama of Paris continued a few more inches to the left it may have captured the Pont de l'Alma and his own small exhibition hall, which was nearing completion, at long last, around the time he began his

View of the Universal Exposition of 1867.

The Manet pavilion finally opened on May 24, with fifty-three canvases on show, including

Music in the Tuileries, The Absinthe Drinker, Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe

and

Olympia.

Manet had spared no expense to make his gallery a success. On the outside, pennants fluttered on flagpoles, while on the inside the walls were hung with red velvet and a divan in the center of the room offered respite to weary visitors. "A perfume of gallantry floats on the air," wrote one of his friends.

16

For good measure, Manet made available copies of Zola's article from the

Revue du XIX

e

Siècle,

which he published in pamphlet form despite some initial reservations. "I think it might be in poor taste," he had written to Zola in March, "and strain our resources to no great advantage, to reprint such an outspoken eulogy of me and sell it at my own exhibition."

17

But he was won over by Zola, who understood a thing or two about publicity from his days at the Librairie Hachette. The pamphlet, handsomely attired in blue slipcovers, was therefore available in bookshops by the time the gallery opened to the public. Likewise on offer was a catalogue for Manet's exhibition, complete with a preface elucidating his motives in showing his work outside the Palais des Champs-Élysées.

Though no doubt composed with the help of Zola, this short article rehashed many of the points that Manet had put to the Comte de Walewski at their meeting in 1863. It explained that Manet's work had attracted criticism from those who followed (and here the preface alluded pointedly to the École des Beaux-Arts) "the traditional teachings concerning composition, technique and the formal aspect of a picture. Those who have been brought up on these principles," it asserted, "countenance no others." Constant rejection by Salon juries adhering to these conservative principles was obviously detrimental to the livelihood of an artist. Deprived of an audience, such an artist "would be obliged to stack up his canvases or roll them up and put them away in the attic." But Manet had decided, the preface stated, "to present a retrospective exhibition of his work directly to the public." Of course, the public had been even more hostile to many of his works than had most members of the Salon juries, but the preface urged visitors to give the paintings a second look. With repeated viewing, the initial "surprise and even shock will give way to familiarity. Little by little," the preface confidently predicted, "understanding and acceptance will follow."

18

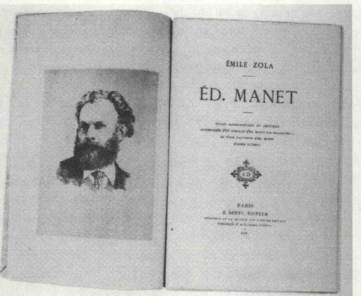

Title page of Zola pamphlet on Manet

(Manetportrait by Filix Bracquemond)

Manet was fraught as the day of the opening approached. "He is in a frightful state," Claude Monet (not yet exiled to Normandy) reported to Bazille after a visit to the pavilion.

19

Despite his efforts and professed optimism, Manet's exhibition proved a comparative failure. He did receive a good notice in

L 'Indipéndance beige

from Jules Clarétie, who called him "a Velázquez of the boulevards" and a "Parisian Spaniard."

20

He also received a glowing report in the

Revue libérale

from Hippolyte Babou, an influential writer and critic who had immortalized himself a decade earlier by providing Baudelaire with the title for

Les Fleurs du mal.

21

But these lines marked the full extent of the blandishments. The other Parisian papers completely ignored the exhibition: no reviews appeared in the

Gazette des Beaux-Arts, L 'Artiste, Le Moniteur,

or any of the other journals that had previously humiliated him with their pungent comments. Critics like Gautier, Saint-Victor and Mantz, busily surveying the other art on show in Paris, all declined to set foot in his little pavilion. One of the few references to the exhibition was in the humorous

Journal amusant,

which dubbed it the "Musée Drôlatique"

22

—the Museum of Drolleries.

Nor was the public any more reliable, since most of the spectators apparently came to laugh. "Never at any time was seen a spectacle of such revolting injustice," fumed Manet's friend Antonin Proust, who claimed the public was "pitiless": "They laughed in front of these masterpieces. Husbands escorted their wives to the Pont de l'Alma. Wives brought their children. The entire world had to avail itself of this rare opportunity to shake with laughter."

23

As usual, Proust was exaggerating. In fact, Manet's pavilion was never really thronged. He began by charging an entrance fee of fifty centimes, half of what Salon-goers paid to get into the Palais des Champs-Élysées. This modest fee meant that in order to recoup his costs he needed to entice 36,000 paying customers into his pavilion, or to make up any shortfall in these numbers with sales of his canvases. The Ingres retrospective at the École des Beaux-Arts drew such crowds, but Manet's name did not possess the same magnetic properties. By the end of June, in a bid to inflate his receipts, he had doubled his entrance fee to a franc.

24