The Judgment of Paris (28 page)

Absent from the government appointees in 1865 was the Due de Morny, whose shrewd guidance had made the previous Salon a success. Morny died on March 10, at the age of fifty-four, ten days before the paintings and statues were due to arrive at the doors of the Palais des Champs-Élysées. His death was officially blamed on pneumonia, though rumors quickly went around Paris that he had expired from a remedy given to him by his personal physician, an expatriate Irishman named Sir Joseph Olliffe. The son of an Irish merchant, Olliffe had risen in life to become a knight of the realm, a physician at the British Embassy in Paris, and an enormously wealthy speculator who in the early 1860s had helped turn the fishing village of Deauville into a fashionable seaside resort. Unfortunately, he was also a quack, and much of his huge fortune had come from prescribing arsenic pills to improve the complexions of well-to-do patients such as Morny. The pills may well have done wonders for skin tone, but they also produced—as Morny appears to have discovered to his cost—the most disagreeable side effects. Morny's death would be felt deeply not only on the painting jury, but also in the Legislative Assembly, the auction rooms and, perhaps most of all, in the fashionable Paris salons where he had ruled as the Second Empire's greatest social lion.

The loss of Morny's moderating influence was compensated for, in part, by the government's appointment of Théophile Gautier and then the announcement that Ernest Meissonier would serve on the painting jury after all, when one of the other jurors declined his post. And among the thousands of paintings awaiting their attentions was the portrait of the nude Victorine Meurent posing as a prostimte. Manet had finally decided to send

Olympia

before the judges.

To the average Parisian, Manet must have seemed a connoisseur of punishment. When he showed his paintings at Louis Martinet's gallery in 1863, visitors had menaced his canvases with their walking sticks, creating a climate of hostility and mockery that led to even more public ridicule two months later at the Salon des Refusés. Yet after moving into his new lodgings he immediately began preparing for a second one-man show at the Galerie Martinet—an act that must have seemed either an act of vainglorious self-confidence or a foolhardy taunting of fate.

Manet's exhibition opened in February, the month before judging was due to begin for the 1865 Salon. Among the eight works he sent to the gallery were two of his "modern life"

plein-air

paintings from the previous summer,

The Races at Longchamp

and

The "Kearsarge " at Boulogne.

He also included a fragment, the dead matador, amputated from his unsuccessful

Incident in a Bull Ring,

together with a number of still lifes of fish and fruit that he had painted in Boulogne. The eight canvases were more cordially received than his show two years earlier. This was due mainly to the fact that his still lifes were perfectly unobjectionable: his paintings of peonies, salmon and bunches of grapes were far less likely to inflame opinion than had most of his previous works. These simple images of fish and fruit spread on white tablecloths showed, Théophile Thoré claimed, "undeniably picturesque qualities."

5

Manet's comparative success seemed to be underscored by the fact that during the exhibition he sold an earlier still life, two flowers in a vase, to Chesneau, who had evidently responded favorably to his overtures. "Perhaps it will bring me luck," Manet wrote to Baudelaire of the sale.

6

Manet dared to grow upbeat about his chances for the Salon. However, if his exhibition at the Galerie Martinet showcased his new artistic direction, his submissions to the 1865 Salon reverted to his more typical style. Despite the rough ride given

Dead Christ with Angels

a year earlier, he decided to offer another portrait of Christ, a canvas

enticed Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers,

painted early in 1865 with a well-known model named Janvier, a locksmith, posing in the title role. As so often in Manet's case, the work was inspired by a painting in the Louvre, this time Titian's

Christ Derided.

He portrayed Christ with his hands bound before him and the crown of thorns on his head as three Roman soldiers gathered around to taunt and threaten him. Once again his Christ—large feet, knobby knees, thin chest, plaintive expression—hardly cut a gallant figure. Nor was Manet especially galvanized by the topic: "I think that's the last time I'll be going for that sort of subject," he wrote to Baudelaire after the piece was finished.

7

If Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers

seemed almost certain to annoy the critics, the decision to submit

Olympia

was even more recklessly daring. The fact that Manet had kept the work hidden in his studio for eighteen months indicates his reservations about showing it in public. Why he decided to launch it on the world in 1865 remains something of a mystery, though Léon Koella later claimed Baudelaire had urged Manet to send it to the Salon.

8

He may also have been persuaded by Zacharie Astruc, who seems to have given the work its title and then composed an execrable poem in its honor. Whoever was responsible, the strange gamble seemed initially to have paid off. Both paintings were accepted for the Salon—though a newspaper reported, ominously, that the jurors had rejected

Olympia

at first.

9

Still, Manet remained optimistic. "From what I hear, it won't be too bad a year," he wrote to Baudelaire on the eve of the Salon's opening.

10

The next day, his sanguinity at first seemed well founded when a number of people rushed over to congratulate him on his work. They were, he was told, the most superb seascapes.

Seascapes? Manet was confused. Taking himself to Room M, he soon discovered the source of the confusion: two canvases,

The Mouth of the Seine at Honfleur

and

The Pointe de la Hève at Low Tide,

signed by an unknown painter named Monet. Manet was indignant. "Who is this Monet," he demanded, "whose name sounds just like mine and who is taking advantage of my notoriety?"

11

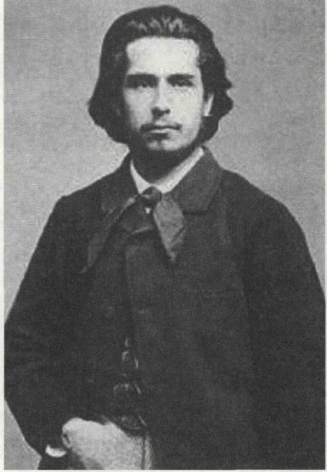

Claude Monet, at the age of twenty-four, was exhibiting at the Salon for the first time. He was a cocksure, competitive and rebellious young man of enormous ambition. The son of a grocer, he had earned a precocious fame in Le Havre, his hometown, for his talents as a caricaturist before falling under the influence of the seascapist Eugène Boudin, the son of a ship's captain and Le Havre's most celebrated painter. After Boudin convinced him to give up caricatures for painting landscapes out of doors, Monet moved to Paris in 1859 to study at the Académie Suisse, a private art studio opened on the Île-de-la-Cite in about 1850 by a former artists' model named Suisse. Gustave Courbet, among others, had paid the small fee of ten francs per month required to study at the school, which offered male and female models, studio space and plenty of camaraderie, but no teachers or program of study—a relaxed regime ideally suited to the rebellious temperament of the young Monet.

Monet's fledgling artistic career had been interrupted when he was drafted into the army in 1860. Most young Frenchmen dreaded military service and took every precaution—including bribery of the relevant officials—to avoid it. Not so, however, the plucky Monet. "The seven years of service that appalled so many," he later boasted, "were full of attraction to me."

12

He was sent to Algeria with the Zouaves, a division of the light infantry that took its name and exotic uniform—turban, baggy trousers, cutaway tunic—from an Algerian tribe. Here he savored the light of the African sun and the color of the desert, not to mention (so he later averred) the "crackling of gunpowder and the thrusts of the sabre."

13

But after little more than a year his military career ended amid the purple spots and fevered delirium of typhus. Obliged to return to France, he divided his time after his recuperation between his studies in Paris, where he entered the studio of Charles Gleyre, and painting expeditions to the Normandy coast, where he encountered his idol, Courbet.

Claude Monet

By 1865 Monet was sharing an apartment in the Rue Furstemberg with Frédéric Bazille, a friend from Gleyre's studio. However, a month before the Salon opened he had departed with his paintbox and his eighteen-year-old mistress, Camille Doncieux, for the village of Chailly-en-Bière, on the edge of the Forest of Fontainebleau, thirty-five miles south of Paris. The forest's rustic enchantments had been celebrated on canvas by Corot, who had painted there as early as 1822, as well as by Jean-François Millet and Théodore Rousseau, both permanent residents of the area by the late 1840s. Inspired in part by the example of their work, Monet was beginning an immensely bold pictorial enterprise, a twenty-foot-wide canvas onto which he planned to paint, in the open air, capturing the interplay of light and shade among the trees, a series of life-size figures in modern dress relaxing over a picnic lunch in the forest.

Monet hoped to have his mammoth new painting ready for the Salon of 1866. In the meantime, he had succeeded in his first attempt to show work at the Salon, since his two Normandy seascapes—one showing sailboats battling winds in rough, muddy waters off the coast of Honfleur, the second a foaming tide retreating from a rocky beach under a leaden sky—suitably impressed the jurors. Better still, the two works soon received exuberant praise from the public and critics alike. Paul Mantz, chief art critic for the

Gazette des Beaux-Arts

and one of the most fearsome reviewers in France, heaped compliments on

The Mouth of the Seine at Honfleur,

singling out its "taste for harmonious colors" and proclaiming it one of the finest seascapes seen at the Salon in recent years.

14

A new star had been born—a star who, most irritatingly for Édouard Manet, shared four fifths of his surname. Manet may have been even more provoked had he known that Monet planned to call his huge new painting

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe.

Zacharie Astruc, who knew both painters, volunteered to introduce Manet to the younger man. But Manet, waving his arm dismissively, stoutly refused the acquaintance.

15

For while his virtual namesake luxuriated in words of exorbitant praise, his own two Salon paintings were meeting with an altogether different fate.

I

WISH I HAD you here, my dear Baudelaire," Manet wrote to his friend, who was still in Brussels, shortly after the 1865 Salon opened. "Insults are beating down on me like hail. I've never been through anything like it."

1

Charles Baudelaire was not the most sympathetic person to whom Manet might have turned. Never one to worry about either the critics or public opinion, Baudelaire thrived on controversy and notoriety. "I'd like to see the entire human race against me," he once wrote. Eager to produce an opprobrious reputation for himself and requite the morbid curiosity of the Belgians, he had recently begun spreading the rumor that he had murdered and then eaten his father. "I am swimming in dishonor like a fish in water," he was soon boasting in letters to friends back in Paris.

2

Baudelaire could not therefore understand Manet's dismay over yet another vitriolic reception for his Salon paintings. As he put it in a letter to a friend, insults and injustice were "excellent things."

3

His response to Manet's plight was a stern letter urging his friend to call to mind artists such as Richard Wagner—an idol of Baudelaire's—who had been forced to contend with both a loutish public and the inane sniping of the critics. "Do you think you are the first man put in this predicament?" Baudelaire upbraided the disconsolate painter. "Are you a greater genius than Châteaubriand or Wagner? And did not people make fun of them? They did not die of it."

4

Still, the boorish protests that drove Wagner's

Tannhäuser

from the Paris stage in 1861 could not compare to the unseemly hubbub that greeted Manet's work at the 1865 Salon, with

Olympia

(plate 4B) provoking an even more incredulous and fiercely hostile reaction than

Music in the Tuileries

or

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe

had two years earlier. "Never has a painting excited so much laughter, mockery and catcalls as this

Olympia,"

wrote one critic in his review of the show.

5

On Sundays, when admission was free, immense crowds poured into Room M, preventing people from getting close to

Olympia

or even circulating through the rest of the room. An atmosphere of hysteria and even fear predominated. Some spectators collapsed in "epidemics of crazed laughter" while others, mainly women, turned their heads from the picture in fright. "Nothing can convey the visitors' initial astonishment," wrote the correspondent for

L'Époque,

"then their anger or fear."

6