The Jewish Annotated New Testament (170 page)

Read The Jewish Annotated New Testament Online

Authors: Amy-Jill Levine

A rough, composite image of the highly fragmentary premodern Jewish conception of Paul finds him portrayed as the innovator of non-Jewish teachings such as the Trinitarian conception of God, the atoning death of Christ, and celibacy, who had modified the calendar, and whose antinomian (anti-

Torah

) misreading of scripture had led him to set aside practices that traditionally separated the Jews from the other nations. But such an image was by no means widespread.

In contrast, early Enlightenment Jewish discussions of Paul were remarkably positive. The Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632–77) in his

Theological-Political Treatise

stressed that the apostle spoke from reason rather than revelation and regarded him as the most philosophical of the apostles. Spinoza wrote as a philosopher, not as a theologian; in fact he had been expelled from the Amsterdam Jewish community in 1656. Since he was not a Christian convert, however, it is reasonable to see his views on Paul as reflecting at least one possible Jewish assessment. The German rabbi Jacob Emden (1697–1776) argued in his

Seder olam rabbah vezutai

that Paul had not sought to denigrate Judaism, had “never dreamed of destroying the Torah,” and was in fact “well-versed in the laws of the Torah.” While Spinoza wrote for a Gentile readership, and Emden wrote to advise the Polish Jewish authorities, both appreciations of this key Christian figure can be seen as strategic in terms of connecting with the wider Gentile world.

In the nineteenth century, German Protestant biblical criticism increasingly viewed Christianity as brought about by Paul’s universalistic teaching. As the cliché states, Paul turned the religion

of

Jesus into the religion

about

Jesus. Among the earliest Jewish proponents of this view was the German scholar Heinrich Graetz (1817–91), whose immensely influential

History of the Jews

(1853–76 [English translation 1891–98]) presented Paul as the “inventor” of Christianity, distinguished Paul’s superficial Jewish learning from Jesus’ high-mindedness and moral purity, and argued that Paul’s antinomian theology made him “the destroyer of Judaism.”

As German Christian scholarship emphasized Paul’s role in injecting pagan elements into the religion of Jesus, it comes as no surprise that the prominent American Reform rabbi, Kaufman Kohler (1843–1926), in his

Jewish Encyclopedia

(1901–16) article on “Saul of Tarsus,” found Gnostic influences and Hellenistic mystery religions to account for many of Paul’s teachings. Even the German philosopher Martin Buber (1878–1965), whose credentials in interfaith relations were impeccable, contrasted the faith (Heb’

emunah

) of Jesus, a Jewish faith that implied relation with and trust in God, with the faith (Gk

pistis

) of Paul, a Christian faith that was premised upon belief in a proposition.

Insofar as it is legitimate to speak of a popular modern Jewish view of Paul—for he barely registers on the Jewish cultural radar—the apostle is regarded not only as the creator of Christianity but also as a Jewish self-hater. The Chief Rabbi of the United Synagogue in the United Kingdom, Jonathan Sacks (1948–), in his 1993

One People?: Tradition, Modernity, and Jewish Unity

, even identified a genocidal ring to the apostle’s teachings, describing him as “the architect of a Christian theology which deemed that the covenant between God and his people was now broken. … Pauline theology demonstrates to the full how remote from and catastrophic to Judaism is the doctrine of a second choice, a new election.

No doctrine has cost more Jewish lives

” [Italics added].

Until recently the majority of Jewish commentators, influenced by the traditional Lutheran teaching that Paul taught freedom from the oppressive yoke of the Law through faith in the Messiah’s redemptive sacrifice, denounced Paul’s apparent derogation and abrogation of the

Torah

as reflected in statements such as “the power of sin is the law” (1 Cor 15.56) and “For all who rely the works of the law are under a curse” (Gal 3.10). The Rumanian scholar and leader of North American Conservative Judaism, Solomon Schechter (1847–1915), captured perfectly in his

Some Aspects of Rabbinic Theology

(1909) the Jewish puzzlement at Paul’s apparent hostility toward the Law: “Either the theology of the Rabbis must be wrong, its conception of God debasing, its leading motives materialistic and coarse, and its teachings lacking in enthusiasm and spirituality, or the Apostle to the Gentiles is quite unintelligible.” Jewish scholars understood Paul’s antinomian stance as either an opportunistic strategy to convert Gentiles (Graetz and Joseph Klausner), or the result of embittered conflict with contemporary Jews (Kohler), or a mistaken reaction against legalism or “works-righteousness” (Buber and Claude Montefiore), or a consequence of Paul’s own frustrated inability to observe its commandments (Hyam Maccoby, Emil Hirsch, Samuel Sandmel).

A few, however, including the German Reform rabbi Leo Baeck (1873–1956), argued that Paul remained authentically Jewish. In his 1952 article “The Faith of Paul” Baeck suggested that like many of his contemporaries, Paul had expected the Law to be transcended (not abrogated) when the messianic age began; the only difference was that this new age had arrived with Jesus. Thus it had not been un-Jewish for him to exclaim, “All things are lawful for me” (1 Cor 6.12) since this closely paralleled the rabbinic teaching that in the “Days of the Messiah … there will be no merit or guilt” (

b. Shabb

. 151a). Many noted that Paul’s apparent readiness to prioritize a universal dimension at the expense of the more particularistic elements of the

halakhah

(religious law) was somewhat similar to the attitude of nineteenth-century Reform Judaism. While traditionalists were condemnatory (in 1925, the Anglo-Orthodox Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz denounced the Reform movement as “an echo of Paul, the Christian apostle to the Gentiles”), some Progressives such as Montefiore, Hans Joachim Schoeps, Samson Raphael Hirsch, Joseph Krauskopf, and Isaac Mayer Wise argued that Paul’s concern to bring the essential teachings of Judaism to the Gentiles was a profoundly Jewish concern, and, admiring his success, they speculated whether there were lessons to be learned from his methods.

More recently, mainstream New Testament scholarship has questioned the assumed antinomian character of Paul’s thought. A number of Jewish scholars are associated with this trend. For example, Mark Nanos (1954–) has gone so far as to claim that Paul was entirely

Torah-

observant and that he expected other Jewish followers of Jesus to be so as well. Nanos interprets the apostle’s negative remarks about the Law as expressing the right of Gentiles to follow Jesus without observing the Law, rather than expressive of dissatisfaction with the Law per se. Modern scholars have also been interested in issues relating to gender and Paul’s attitude toward women. Against Christian feminists who see the apostle as sexist and placing restrictions on women as a result of his rabbinic training, Amy-Jill Levine (1956–) points out the anachronism of the charge: that Paul belonged to no rabbinic school, and that the rabbinic literature is of a much later date. She further suggests that Paul would have been familiar with women leaders in Diaspora synagogues, and thus recognized women leaders in his churches (e.g., Phoebe the deacon and Junia the apostle [Rom 16]). One might even begin to talk of a sort of Jewish reclamation of the Jewish Paul. Daniel Boyarin (1946–) maintains that despite the fact that Paul had found the Law problematic, his letters (“the spiritual autobiography of a first-century Jew”) show him to be a Jew facing many of the same kinds of challenges that Jews face today; furthermore, as a fellow “cultural critic” Paul had asked the right questions (regarding universalist and gender issues in particular) in terms of how Jews should relate to the non-Jewish world.

The classic, negative view of Paul tends to emphasize Paul’s Diaspora roots and to locate him within an essentially pagan environment. Kohler and Buber, among others, locate “Paulinism” (i.e., the pessimistic exaggeration of the power of sin and the belief in enslavement of the cosmos) in a heathen world of idolatrous sacrifice, mysteries, and demonic forces. This perspective found its final expression in the eccentric theory of the Ukrainian Zionist writer Micah Berdichevsky (1865–1921), who, determined to expose the essentially non-Jewish origins of the apostle and hence of Christianity itself, argued that Saul and Paul were different people, one a Jew and the other a pagan priest from Damascus. The Anglo-Orthodox scholar Hyam Maccoby (1924–2004) also argued for the Gentile origins of the “inventor of Christianity,” maintaining that his poor emulation of rabbinic arguments (e.g., in Rom 7.1–6, where he discusses the limits of the Law) showed that he could not have been a Jew, and certainly not a Pharisee.

Others have had less difficulty placing Paul in an explicitly Jewish context. Among those who regarded him as a Hellenistic Jew, for example, were the founder of Anglo-Liberal Judaism, Claude Montefiore (1858–1938) and the American leading scholar of Jewish-Christian relations, Samuel Sandmel (1911–79). Montefiore suggested that Paul’s apparent complaints concerning Judaism and the Law had reflected his experiences of this inferior form of Judaism; thus Paul should

not

be regarded as an enemy of rabbinic Judaism. Others, from Wise in 1883 to the American scholar Alan Segal (1945–2011) in 1990, attending to Paul’s vision of paradise in 2 Corinthians 12.2 (“I know a person in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know”), attribute to Paul an education in Jewish mysticism. Hugh Schonfield even argued in his 1946

The Jew of Tarsus: An Unorthodox Portrait of Paul

, that Paul’s Letter to the Romans parallels parts of the Jewish liturgy.

Broadly speaking, the Jewish relationship with the apostle to the Gentiles has been, and remains, a bitter one. He was largely ignored until the Enlightenment, with Jewish interest gathering real momentum only in the nineteenth century, in tandem with the growth of Protestant biblical scholarship. Thereafter Paul was frequently lambasted as the real founder of Gentile Christianity, under whose influence the lachrymose history of the Jews unfolded. In contrast to the figure of Jesus, who has, in the main, been reclaimed as a good Jew of one sort or another, Paul remains an object of hostility and suspicion. While there have been a number of scholarly exceptions to this rule, one should not expect him, whose likening of the Law to “sin” and “death” still echo down the centuries, to enjoy a more general Jewish reclamation any time soon.

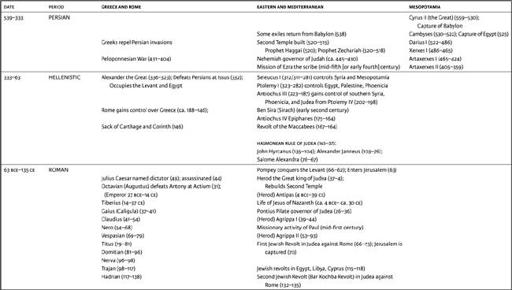

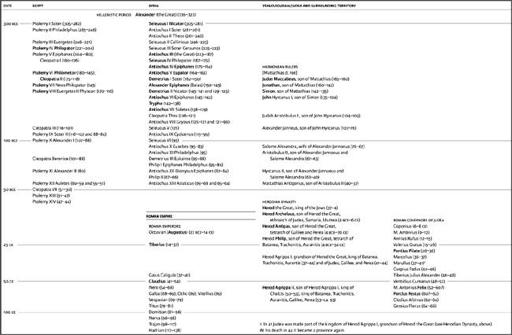

TIMELINE

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE OF RULERS

SOME TANNAITIC RABBIS

FIRST GENERATION

Gamaliel (sometimes called “the Elder”; late 1st century BCE)

Shimeon ben Gamaliel (1st century CE)

Yoḥanan ben Zakkai (1st century CE)

SECOND GENERATION

Elder

Gamaliel II (of Yavneh; son of R. Shimeon; born ca. 50 CE)

Eliezer ben Hyrcanus (pupil of R. Yoḥanan ben Zakkai; 1st–2nd century)

Yehoshua ben Ḥananiah (pupil of R. Yohḥanan ben Zakkai; 1st–2nd century)

Younger

Akiva ben Yosef (ca. 40–135)

Ishma’el (or Yishma’el) ben Elisha (early 2nd century)

Elishah ben Avuya (late 1st–early 2nd century)