The Jewel Trader Of Pegu

In memory of my mother,

Lonnie Hantover

Every day redemption is worked for him,

as for those who went out of Egypt.

—

THE

MIDRASH

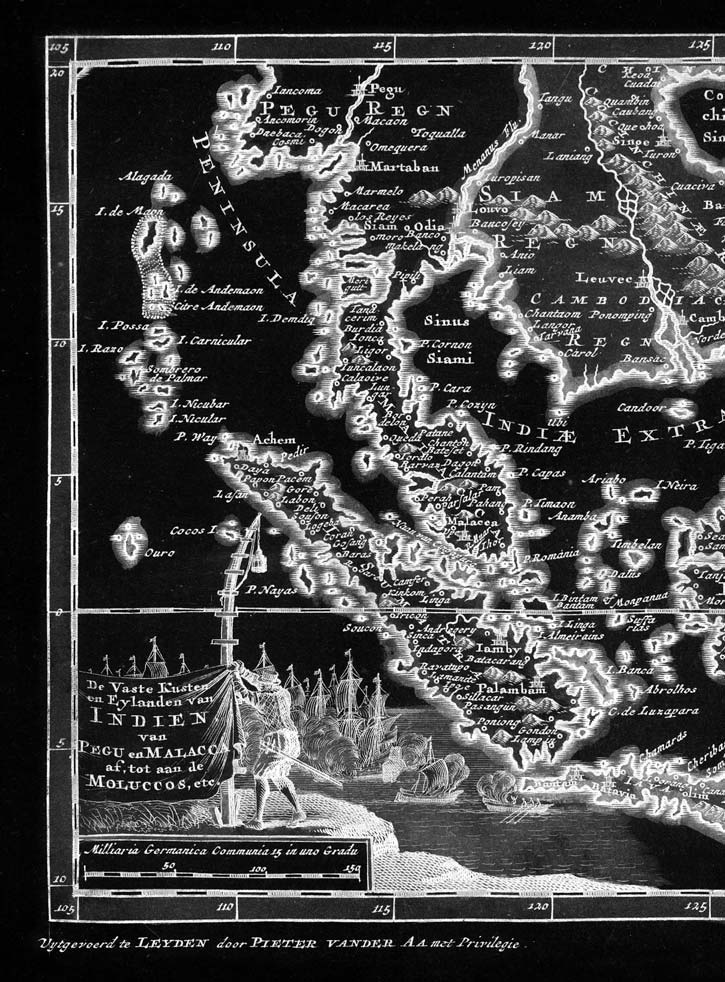

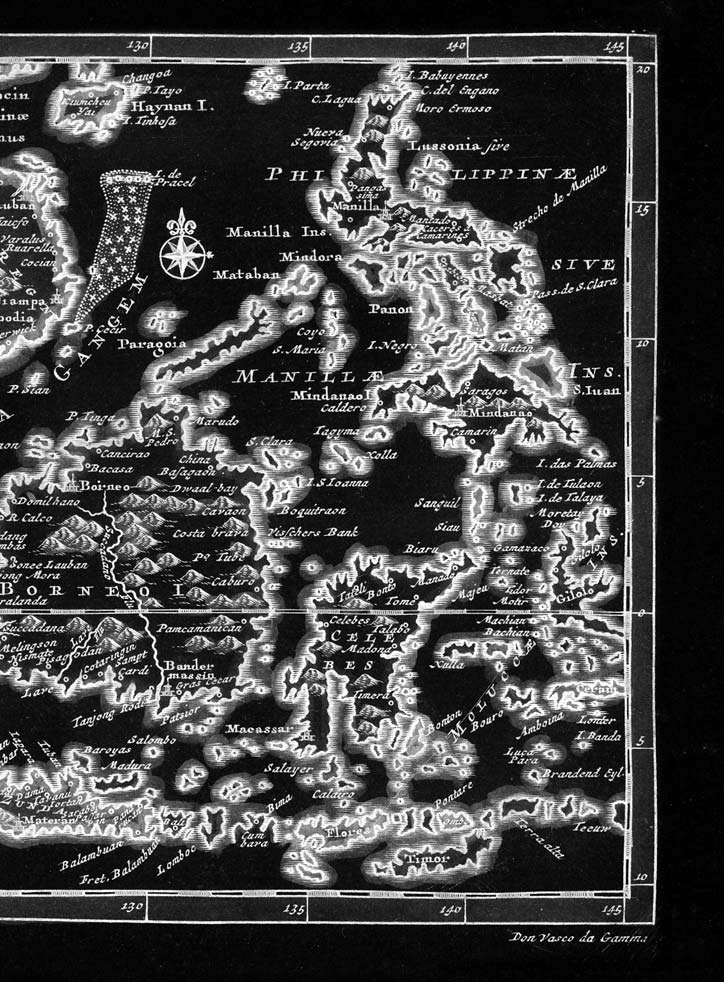

Map

The shorelines and islands of (the East) Indies from the Pegu and Malacca axis, till the Moluccas, etc.; 1707

The king [Sigismund Augustus Jagiellon, king of Poland] takes extreme delight in jewels, and he showed them to me one day in secret, for he does not want the Poles to know that he has spent so much to buy them. There is in his chamber a large table, almost as big as the room itself, on which stand sixteen jewel cases two spans long and a span and a half wide, filled with jewels. Four cases having belonged to his Mother are worth 200 thousand crowns and were brought from Naples. Four others were bought by his Majesty for 500 thousand gold crowns. They contain: a clasp from Charles V, which is worth 30 thousand gold crowns, and his diamond-studded medal big as a gold ducat, having on one side the eagle with the arms of Spain, on the other, Charles V’s personal motto: two columns bearing the inscription “plu ultra.” There are, besides, many square and pointed rubies, and emeralds. The other eight cases are very old, one of them containing a bonnet full of emeralds, rubies and diamonds, which are worth 300 thousand gold crowns. I saw, finally, many jewels which I did not expect to find, and with which neither those of Venice which I have likewise seen nor those of the papacy can be compared.

—

BERNAR

DBONGIOVANNI

,

Papal Ambassador to Poland, 1560

In 1614 Father Jorge de Silva, a young priest fresh from the sem-inary in Lisbon, traveled upriver to the ruined city of Pegu. The royal palaces and golden temples were burnt memories. There were few native souls to save or foreign ones to keep from stray-ing into the barbarism he had been warned the lush and sensuous country and half-naked women induced. He had read of strange wonders in the lands “beneath the wind”: islands where children were fathered by the wind and all males were strangled at birth; creatures with the faces of maidens and the tails of scorpions; lands where people worshipped the first creature they met in the morning, whether it walked on two legs or four; and a race of men who ate raw flesh and hunted upon the backs of green-scaled beasts the size of horses, that had three horns in the middle of their foreheads and short wings like the fins of fishes and could leap thirty paces at a time. He kept paper and pen dry in a leather chest to record the wonders he would see, but he had seen little of note and his journal (now housed in the Vatican Library) is more an account of his troubled constitution and intestinal woes than the exotic world he had hoped to find. Looking for the extraordinary, he failed to see the ordinary.

He did remark on one strange occurrence that led him in his later years to propose with some modicum of conviction that the Burmese were the lost tribe of Israel descended from the Israelites of Judea who had wandered eastward in the days of King Solomon, in search of the kingdom of Ophir. One morning in the market he saw a boy, likely thirteen or fourteen—the child himself did not know when he was born—whose face was different from the other young men sitting on their haunches. His hair was auburn and tightly curled, his eyes rounder. Most striking was his nose: not flat and broad like his countrymen but narrow, with a slight hump in the middle. He had to Father de Silva “the look of the Semites.” That was what first caught Father de Silva’s eye. Then he saw glittering against the boy’s brown chest a small silver pendant hanging on a thin silver chain. On the scratched and tarnished silver square was etched a five-fingered hand pointing downward, and across the palm were several Hebrew characters so worn that the priest could not have deciphered them even if he had been trained to read the language. He recognized it to be an amulet worn by Jews to protect themselves from the evil eye and all manner of illness and danger.

The boy knew nothing of its history or what it meant. He simply had worn it all his life. Perhaps, he said, he had been born with it.

27 September 1598

Dearest Joseph,

I long to wake up on solid ground. The halcyon nests calmly on the waves, but I was born for the stones of our Most Serene City.

You should soon receive a large pouch of letters that I gave to Mordecai Halevi of Mantua, whose niece you know. Since leaving Masulipatnam, I have not encountered any Italian, Gentile, or Israelite with whom I could entrust my letters. Though it may be a year before you read this letter, writing it bears me closer to home. Like a lodestone, my words draw me back to where my heart desires to be.

I live in two worlds: the world where I am, whether it be a bark floating down the Euphrates or this ship riding the waves in the Bay of Bengal, and the world where I wish to be, safe among kin and community. During the day I try to imagine where you might be at that hour. In the early morning as I watch the sails being hoisted to catch the wind, I see you dragging your feet slowly across the Campiello della Scuola and rubbing the sleep from your eyes on your way to the synagogue. In the early evening when the light fades, I think of you slapping your thigh to count the beat, calling out to youth more awkward than I the graceful steps of the galliard. Or unrepentant, are you slipping away to find pleasure in a forbidden bed?

Uncle will be proud that I have tried, as he instructed when we were young, to write a letter a day. I imagine those daily letters that traveled but a few feet from my bedroom to his eased him quickly to sleep with their dull depiction of days repetitive and unevent-ful. I could not twist and twirl words with his dexterity nor lather my thoughts with allusions so rich and layered that a second letter would be required to make clear the first. If my letters now show some spark, it comes less from my skills as a humble servant of words and more from the strangeness of the world that lies beyond the Lagoon. I have seen enough wonders to turn the Grand Canal black with ink.

I turned twenty-eight at sea, a fact I kept to myself because it was no cause for celebration, especially among strangers with whom I have no history. Well over a year has passed since this journey began and we were together. Though now two years older than you, when I return I should be much more your elder cousin, as I am told one ages rapidly in these climes.

There are still no other Israelites on the ship, but my treatment has been agreeable. Some barely speak to me; but I take no offense because I think perhaps they fear the effort and influx of air may trouble even more their churning stomachs. There are a few, closer to home, whose eyes betray all the ancient fears. Yet for now we Europeans are equal—strangers made one by our discomfort and our hopes for shore and home. Equal in the amusement we provide the Gujaratis, Malays, Siamese, Peguans, and all the other brown-faced heathens aboard; and, if I could understand their tongues, equal, I imagine, in their disdain. We are, in their eyes, big-nosed, hairy barbarians, loud, clumsy, lacking in their quiet grace. Perhaps, cousin, if they saw you dancing the

ballo del fiore

, they might reconsider a portion of their prejudice and ridicule, but only a portion—you too would be lumped a barbarian with us all, Gentiles and Israelites. I have had to travel half a world away, but triumph at last: though my legs may wobble with the waves, I stand an equal to the Gentiles.

I know you would not be at ease among these heathens. You are happy where you are and were honest in saying that you would never journey so long and so far from all you have ever known. Even Uncle chuckled when you said you could not imagine living among strangers who would not smile when you entered the room or laugh at your jokes. I remember your impatience when Jacob Levi loudly boasted that he was ready for adventure and would gladly leave the next day in my place. You silenced him, perhaps a bit too sharply, saying he knew full well that tomorrow would find him safely at his father’s side, under the blue awning of their pawnshop, and his only adventure would be flipping through the pages of the pledge book.

We hug the coast like a child his mother and put into harbor at the least sign of bad weather. North up the Bengal coast and now south along the coast of Burma—you can trace my journey on Uncle’s map. Yesterday we lay becalmed near a headland thick with tall palms. The sailors stood upon the deck facing the stiff, lifeless palms and whistled for the wind. I guess they believed this would get the ear of their gods. At first they whistled softly, like aunts cooing over a baby. Then they stamped their bare feet on the deck and between shrill whistles cursed the heavens, or so it seemed by their bulging eyes and grimaces. Their gods remained deaf—or simply lazy.

In the ship’s hold, among the tightly packed boxes of cloth we bought in Surat, is red Gujarati cotton I am told the Peguans value highly because the more it is washed the redder it becomes. How nature seems to reverse itself in this part of the world. Soon I shall find a people who are born old and grow younger with each passing year. I have seen on my long journey people who behave in ways fit for the asylum. I have seen people who bow down to cows and paint their houses with the cows’ dung, and beggars, thought holy as saints, walking naked in the market, their fingernails long as knife blades, their uncut beards and hair covering their privates. Until you sail beyond the Mediterranean, you have not seen the fullness of humanity.

As Uncle instructed, I trade with respect and a face that keeps my thoughts hidden; but still I find it strange how each man values goods that for another are common. As dear Dante reminds us

“how ludicrous and brief are all the goods in Fortune’s ken.” Yet on this ship at the edge of the world are almost one hundred men and a half dozen women who would die for a piece of painted cloth or a bag of pepper or cloves. Do they look at me and think, what an odd creature that risks his life to put colored stones on the fingers of strangers?

The city of Pegu awaits us in a fortnight. The few Peguans aboard the ship, men and women, frighten me. They, like us, have two arms, two legs, and by appearance are human—they do have thumbs, so I do not think them devils. But the men are covered from navel to knee and below with all kinds of wild and strange creatures burned into their skin: lions, tigers, monkeys, fierce tusked boars, and the glowering spirits and demons that infest their imagination. Their thighs are thick with numbers and letters meant to keep them safe from the swords and bullets of their enemies. I do not know what would scare away the daggers of their enemies more, these grotesquely tattooed men or their women, their faces painted with yellow powder and paste and sagging ears long as palm leaves with holes a man could stick his fist through.

We should, with good winds, arrive in Cosmin in three days, and from there I will travel upriver another eight or nine days until I reach my destination and our business begins. All that has come before is necessary prologue to the business given me to carry out. I know I must stay a year in order to draw the best advantage from the stone trade here, but it will be a year whose days will move more slowly than an old man creaking up the stairs. Remember that after a year among the idolaters, it will take another year’s travel across ocean and desert to arrive home. It is obligation to our uncle and our business that takes me to strange lands far from home. You know better than anyone that I am not one to seek adventure or repute. All I desire is a bed that does not rock with the wind and tides, and a quiet life lived in peace among those I have known, whatever their failings.