The James Bond Bedside Companion (55 page)

Read The James Bond Bedside Companion Online

Authors: Raymond Benson

The other artistic element of the formula that always helps make or break a 007 film is the musical score. Usually, one man's name is synonymous with James Bond music: John Barry.

Barry was born in 1933, and is one of the most respected names in film scoring today. He has won two Academy Awards (

Born Free

, 1966, and

The Lion in Winter

, 1968), and has composed music for many films, including

The L-Shaped Room

(1962), The

Ipcress File

(1965),

Midnight Cowboy

(1969),

The Day of the Locust

(1975), and

The Black Hole

(1979). He scored all but four of the Bond pictures.

Barry's music for the Bond films is stirring and dynamic. Most of it consists of a big-band jazz sound with electrical instruments (especially guitars), a bit of brass, and, often, exotic instruments such as gongs and harps. Each Bond film features a title tune, all but two of them with lyrics. The title songs for

Goldfinger

and

You Only Live Twice

were both hits, as were three non-Barry efforts:

Live and Let Die

(by Paul and Linda McCartney), "Nobody Does It Better" from

The Spy Who Loved Me

(by Marvin Hamlisch and Carole Bayer Sager), and

For Your Eyes Only

(by Bill Conti and Michael Leeson). The songs accompany the main title designs, usually the work of Maurice Binder, and the union is beautiful to the eyes and ears. Usually featured

with the main titles are silhouetted nudes, as well as gun and spy motifs.

Soundtrack albums of the Bond films have sold well too, which is further proof that the music is an important ingredient in their success. John Barry became famous as a result of the Bond music (though, surprisingly, he has never been nominated for an Oscar for a Bond score). Each soundtrack will be discussed in the appropriate film's section.

PRODUCTION

T

he first James Bond film was produced for only a million dollars, and is one of the best of the series. It is simple, compared to the rest of the films, and this is the main reason for its success. There is no gadgetry in the film—007 relies on his wits and strength to accomplish his mission. Characters are well drawn and the plot is tight and moves quickly. The film is rough, tough, and exciting, with what is probably Sean Connery's most accomplished and sincere performance as James Bond.

Interiors were shot at Pinewood Studios in England, while location shooting took place in Jamaica. Broccoli's idea of the set-piece format is immediately apparent in the first few scenes. First, we see the sequence in Kingston in which Strangways and his secretary are murdered by the three-blind-mice henchmen. Then there is a cut to London, where we see the communications network of the Secret Service. The scene moves from there to a casino where we first meet James Bond. The "bumps" in

Dr. No

follow a logical cause-and-effect sequence (not always true in later films), and the editing prowess of Peter Hunt keeps the film moving with suspense.

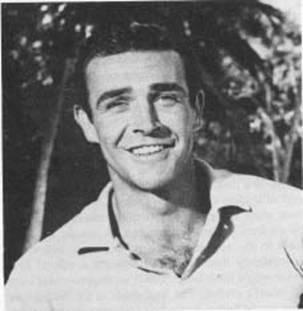

Sean Connery takes a breather and grins for the cameras on location in Jamaica for the filming of

Dr. No.

He's wearing James Bond's "Sea Island" cotton shirt. (UPI Photo.)

Dr. No is

the most violent, and one of the most realistic of the films. Save for the science fiction elements of Dr. No's laboratory and his plan to topple U.S. missiles, the bulk of the film is based in reality. The fight scenes, coordinated by Bob Simmons, are tough and believable. There is one scene which captures the essence of Bond's profession as a killer, something that has been largely ignored in subsequent films. Bond is waiting at Miss Taro's house for the arrival of would-be assassin Professor Dent. (Dent and Taro are a pair of Dr. No's underlings—characters created for the film.) Bond is sitting behind the bedroom door after having stuffed the bed full of pillows to resemble a body. Dent opens the door quietly and empties his gun into the shape in the bed. Bond then makes his presence known and orders Dent to drop the gun. After asking Dent a few questions, 007 calmly shoots the man in cold blood. He even fires a superfluous bullet into the fallen man's back! Bond then removes the silencer from his gun and nonchalantly blows the smoke away. The scene fades out quietly.

The above sequence is one of the most effective moments in the entire James Bond film series, yet it caused considerable controversy at the time of release. Director Terence Young fought hard for the scene to remain intact, insisting that Bond "is an executioner—we must not forget that." It is a scene that captures Fleming's Bond perfectly, and Connery plays it with ruthlessness. Unfortunately, this was to be the only sequence of its kind in the series. In each of the following films, the violence is toned down considerably, and Bond would never kill anyone with such methodical coldness again.

Humor in

Dr. No

takes the form of tongue-in-cheek innuendos and one-liner asides. The humor is subtle and avoids the juvenile, an achievement which eludes the later Bond films.

Ursula Andress, playing the first screen Bond-girl, Honeychile Rider, adjusts her costume before shooting a scene in

Dr. No

. (UPI Photo.)

SCREENPLAY

A

s would be the case with all the James Bond films, the screenplay departed in several instances from the Ian Fleming novel (although compared to some of the later films,

Dr. No

seems extremely faithful). The novel's premise seems fairly improbable. The decision was made to discard some of Fleming's more fantastic elements and attempt to create a more believable chain of events. But in doing so, a great deal was lost as well. The alterations in

Dr. No

are not as extreme as in some of the later films, in which Fleming's plot is sometimes

completely

jettisoned.

Screenwriter Richard Maibaum (with the aid of Johanna Harwood and Berkley Mather) added a lengthy midsection to the story involving Professor Dent and Miss Taro. These sequences add weight to the middle of the film and are actually improvements over Fleming's original story. Other changes include the introduction of SPECTRE, mainly because the producers knew this criminal organization would figure prominently in later films. (Maibaum had worked on a screenplay for

Thunderball

before the decision was made to start the series with

Dr. No

. SPECTRE was originally created for

Thunderball

. Maibaum was perhaps influenced by this story as well.) SPECTRE is only mentioned briefly by Dr. No in the film, as a hint of things to come. Another addition is the inclusion of the Felix Leiter character. Bond's CIA friend appears in several of the novels, but not DOCTOR NO; apparently Maibaum felt that the Bond ally in this story, Quarrel, was not a strong enough character. But frankly, the addition of Leiter is extraneous to the dramatic action; the character doesn't serve any major function.

A disappointing change from the novel is the substitution of a tarantula for the centipede which crawls on Bond's body while he's in bed. The producers probably felt that audiences wouldn't realize that a centipede is lethal. Tarantulas are creatures everyone can recognize. Unfortunately, the filming of this scene isn't as successful as it probably looked on paper. Due to clumsy camera work and special effects, it is embarrassingly apparent that there is a sheet of glass between Connery's arm and the spider.

The most important change is in the last reel, beginning with the obstacle course sequence. In the novel, the ventilation shaft through which Bond makes his escape is a planned-out gauntlet containing all sorts of horrors, ending with a drop into a lagoon containing a man-eating giant squid. In the film, the shaft is not an obstacle course, but merely a harrowing means of escape from the cell. Bond is shot by some unidentified gun which only causes him some pain and doesn't seriously harm him. Next he encounters hot metal around the chute, as in the novel, but gone are the cage of spiders and the giant squid. The film's climax takes place in Dr. No's laboratory, where Bond foils the madman's plans to topple a U.S. missile. Dr. No's death in the nuclear reactor pool is more believable cinematically than his death beneath a pile of bird guano might have been. This is an improvement over the novel's ending. The final shots of

Dr. No

feature what would become standard operating procedure for the series: the villain's establishment is spectacularly blown up, as Bond and his girl (in this case, Honey) barely escape by boat.

DIRECTION

I

t is difficult, in a Bond film, to determine if a particular sequence's success is the work of the director, the actor, the scriptwriter, or the editor. Broccoli insists that the films are collaborative efforts, and that no one person should receive credit for a film's success. But it would be unfair to underestimate the contribution Terence Young made to the James Bond films. In an interview for

Bondage

magazine, Young claims that he originated the style of the series:

Well, without being arrogant, that was established very simply, on the floor, by me. I knew what I wanted. I didn't think the picture was going to be anywhere near as popular as it was. I thought it was going to be a thing for rather highbrow tastes. I thought an awful lot of the jokes were going to be in-jokes. I think it caught on very well . . .

When you analyze it and this is no disrespect to Ian, they (the books) were very sophisticated "B"-picture movie plots. If someone tells you, "a James Bond film," you'd say, "My God, that's for Monogram," or Republic Pictures, who used to be around in those days. You would have never thought of it for a serious "A" film. But it had considerable sophistication, and this was very consciously put in by Ian . . .

One wanted the films to have a very slick quality. We wanted to make them as sophisticated as we could, and above all I gave the picture an enormous sense of tempo, in fact, it changed styles of filmmaking.

(From "The Terence Young Interview" by Richard Schenkman,

Bondage

Number 10)

Young and editor Peter Hunt worked hand in hand to create this tempo and it's a style that stuck throughout the series. At first, Young remembers, Hunt was mortified by the cuts he was asked to make. But after a screening of a rough cut, Hunt was very enthusiastic, and on

From Russia With Love,

the editor was cutting the film with an outrageous extroverted zeal. According to Young, the head of the Cinémathèque in France declared that

Dr. No

was "one of the great innovative films. Years from now, all films will be made like this." Television action films especially adopted the editing style of

Dr. No.

Young's style tends to be slightly more realistic than that of other Bond directors. All of the more violent scenes in Young's efforts are presented with a hard-edged seriousness, save for the exaggerated sound effects. The murders of Strangways and his secretary

at the beginning of

Dr. No

may be the bloodiest scenes in all of the films. The sequence in which Quarrel's face is slashed by a broken flash cube is unnerving. Because this violence is portrayed with some degree of realism, the humor in the film comes as a pleasant surprise. This element boosted the series' success: the audience is released from a tense action scene by a witty one-liner from Bond. The juxtaposition of gravity with levity was probably Terence Young's idea (with the aid of Connery's ad libs), and it is what makes the Bond films so much fun to watch. Unfortunately, the later films lost touch with this key element, and began to play the serious action scenes for laughs as well.