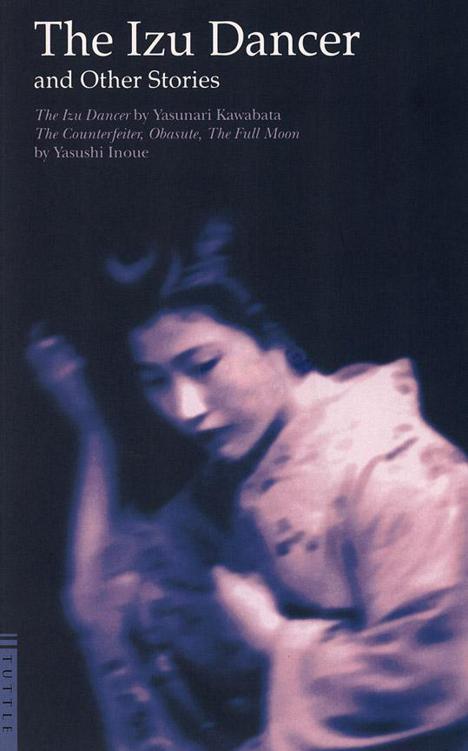

The Izu Dancer and Other Stories: The Counterfeiter, Obasute, The Full Moon

Read The Izu Dancer and Other Stories: The Counterfeiter, Obasute, The Full Moon Online

Authors: Yasushi Inoue,Yasunari Kawabata

BOOK: The Izu Dancer and Other Stories: The Counterfeiter, Obasute, The Full Moon

13.56Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The Izu Dancer

and Other Stories

The Izu Dancer

and Other Stories

The Izu Dancer

by Yasunari Kawabata

The Counterfeiter, Obasute, The Full Moon

by Yasushi Inoue

TUTTLE PUBLISHING

Tokyo · Rutland, Vermont · Singapore

Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions, reprinted with permission of the Asia Society from

Perspective of Japan

, originally published by

The Atlantic Monthly,

December 1954, for Intercultural Publications, Inc.

Copyright in Japan, 1954 by the Asia Society, N.Y.

Yasushi Inoue,

The Counterfeiter, Obasute,

and

The Full Moon

, translated by Leon Picon

All rights reserved

LCC Card No. 74078150

ISBN-13: 978-1-4629-0216-3

First published, 2004

First Tuttle edition, 1974

Originally published under ISBN-10: 0-8048-1141-5; ISBN-13: 978-0-8048-1141-5

Distributed by

North America, Latin America & Europe

Tuttle Publishing

364 Innovation Drive

North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 U.S.A.

Tel: 1 (802) 773-8930; Fax: 1 (802) 773-6993

[email protected]

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Japan

Tuttle Publishing

Yaekari Building, 3rd Floor; 5-4-12 Osaki

Shinagawa-ku; Tokyo 141 0032

Tel: (81) 3 5437-0171; Fax: (81) 3 5437-0755

[email protected]

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd.

61 Tai Seng Avenue, #02-12 Singapore 534167

Tel: (65) 6280-1330; Fax: (65) 6280-6290

[email protected]

www.periplus.com

10 09 08 07 6 5 4 3 2

Printed in Singapore

TUTTLE PUBLISHING

®

is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Izu Dancer | 9 |

| | by Yasunari Kawabata |

translated by Edward Seidensticker | |

The Counterfeiter | 39 |

by Yasushi Inoue | |

translated by Leon Picon | |

Obasute | 95 |

by Yasushi Inoue | |

translated by Leon Picon | |

The Full Moon | 119 |

by Yasushi Inoue | |

translated by Leon Picon |

THE IZU DANCER

by Yasunari Kawabata

translated by Edward Seidensticker

THE IZU DANCER

(

Izu no Odorico

)

I

A SHOWER swept toward me from the foot of the mountain, touching the cedar forests white, as the road began to wind up into the pass. I was nineteen and traveling alone through the Izu Peninsula. My clothes were of the sort students wear, dark kimono, high wooden sandals, a school cap, a book sack over my shoulder. I had spent three nights at hot springs near the center of the peninsula, and now, my fourth day out of Tokyo, I was climbing toward Amagi Pass and South Izu. The autumn scenery was pleasant enough, mountains rising one on another, open forests, deep valleys, but I was excited less by the scenery than by a certain hope. Large drops of rain began to fall. I ran on up the road, now steep and winding, and at the mouth of the pass I came to a teahouse. I stopped short in the doorway. It was almost too lucky: the dancers were resting inside.

The little dancing girl turned over the cushion she had been sitting on and pushed it politely toward me.

"Yes," I murmured stupidly, and sat down. Surprised and out of breath, I could think of nothing more appropriate to say.

She sat near me, we were facing each other. I fumbled for tobacco and she handed me the ash tray in front of one of the other women. Still I said nothing.

She was perhaps sixteen. Her hair was swept up in mounds after an old style I hardly know what to call. Her solemn, oval face was dwarfed under it, and yet the face and the hair went well together, rather as in the pictures one sees of ancient beauties with their exaggerated rolls of hair. Two other young women were with her, and a man of twenty-four or twenty-five. A stern-looking woman of about forty presided over the group.

I had seen the little dancer twice before. Once I passed her and the other two young women on a long bridge half way down the peninsula. She was carrying a big drum. I looked back and looked back again, congratulating myself that here finally I had the flavor of travel. And then my third night at the inn I saw her dance. She danced just inside the entrance, and I sat on the stairs enraptured. On the bridge then, here tonight, I had said to myself: tomorrow over the pass to Yugano, and surely somewhere along those fifteen miles I will meet them—that was the hope that had sent me hurrying up the mountain road. But the meeting at the tea-house was too sudden. I was taken quite off balance.

A few minutes later the old woman who kept the teahouse led me to another room, one apparently not much used. It was open to a valley so deep that the bottom was out of sight. My teeth were chattering and my arms were covered with goose flesh. I was a little cold, I said to the old woman when she came back with tea.

"But you're soaked. Come in here and dry yourself." She led me to her living room.

The heat from the open fire struck me as she opened the door. I went inside and sat back behind the fire. Steam rose from my kimono, and the fire was so warm that my head began to ache.

The old woman went out to talk to the dancers. "Well, now. So this is the little girl you had with you before, so big already. Why, she's practically a grown woman. Isn't that nice. And so pretty, too. Girls do grow up in a hurry, don't they?"

Perhaps an hour later I heard them getting ready to leave. My heart pounded and my chest was tight, and yet I could not find the courage to get up and go off with them. I fretted on beside the fire. But they were women, after all; granted that they were used to walking, I ought to have no trouble overtaking them even if I fell a half mile or a mile behind. My mind danced off after them as though their departure had given it license.

"Where will they stay tonight?" I asked the woman when she came back.

"People like that, how can you tell where they'll stay? If they find someone who will pay them, that's where it will be. Do you think they know ahead of time?"

Her open contempt excited me. If she is right, I said to myself, then the dancing girl will stay in my room tonight.

The rain quieted to a sprinkle, the sky over the pass cleared. I felt I could wait no longer, though the woman assured me that the sun would be out in another ten minutes.

"Young man, young man." The woman ran up the road after me. "This is too much. I really can't take it." She clutched at my book sack and held me back, trying to return the money I had given her, and when I refused it she hobbled along after me. She must at least see me off up the road, she insisted. "It's really too much. I did nothing for you—but I'll remember, and I'll have something for you when you come this way again. You will come again, won't you? I won't forget."

So much gratitude for one fifty-sen piece was rather touching. I was in a fever to overtake the little dancer, and her hobbling only held me back. When we came to the tunnel I finally shook her off.

II

LINED on one side by a white fence, the road twisted down from the mouth of the tunnel like a streak of lightning. Near the bottom of the jagged figure were the dancer and her companions. Another half mile and I had overtaken them. Since it hardly seemed graceful to slow down at once to their pace, however, I moved on past the women with a show of coolness. The man, walking some ten yards ahead of them, turned as he heard me come up.

"You're quite a walker. . . . Isn't it lucky the rain has stopped."

Rescued, I walked on beside him. He began asking questions, and the women, seeing that we had struck up a conversation, came tripping up behind us. The man had a large wicker trunk strapped to his back. The older woman held a puppy in her arms, the two young women carried bundles, and the girl had her drum and its frame. The older woman presently joined in the conversation.

"He's a highschool boy," one of the young women whispered to the little dancer, giggling as I glanced back.

"Really, even I know that much," the girl retorted. "Students come to the island often."

They were from Oshima in the leu Islands, the man told me. In the spring they left to wander over the peninsula, but now it was getting cold and they had no winter clothes with them. After ten days or so at Shimoda in the south they would sail back to the islands. I glanced again at those rich mounds of hair, at the little figure all the more romantic now for being from Oshima. I questioned them about the islands.

"Students come to Oshima to swim, you know," the girl remarked to the young woman beside her.

"In the summer, I suppose." I looked back.

She was flustered. "In the winter too," she answered in an almost inaudible little voice.

"Even in the winter?"

She looked at the other woman and laughed uncertainly.

"Do they swim even in the winter?" I asked again.

She flushed and nodded very slightly, a serious expression on her face.

"The child is crazy," the older woman laughed.

From six or seven miles above Yugano the road followed a river. The mountains had taken on the look of the South from the moment we descended the pass. The man and I became firm friends, and as the thatched roofs of Yugano came in sight below us I announced that I would like to go on to Shimoda with them. He seemed delighted.

In front of a shabby old inn the older woman glanced tentatively at me as if to take her leave. "But this gentleman would like to go on with us," the man said.

"Oh, would he?" she answered with simple warmth. " 'On the road a companion, in life sympathy,' they say. I suppose even poor things like us can liven up a trip. Do come in-we'll have a cup of tea and rest ourselves."

We went up to the second floor and laid down our baggage. The straw carpeting and the doors were worn and dirty. The little dancer brought up tea from below. As she came to me the teacup clattered in its saucer. She set it down sharply in an effort to save herself, but she succeeded only in spilling it. I was hardly prepared for confusion so extreme.

"Dear me. The child's come to a dangerous age," the older woman said, arching her eyebrows as she tossed over a cloth. The girl wiped tensely at the tea.

The remark somehow startled me. I felt the excitement aroused by the old woman at the tea-house begin to mount.

An hour or so later the man took me to another inn. I had thought till then that I was to stay with them. We climbed down over rocks and stone steps a hundred yards or so from the road. There was a public hot spring in the river bed, and just beyond it a bridge led to the garden of the inn.

We went together for a bath. He was twenty-three, he told me, and his wife had had two miscarriages. He seemed not unintelligent. I had assumed that he had come along for the walk-perhaps like me to be near the dancer.

A heavy rain began to fall about sunset. The mountains, gray and white, flattened to two dimensions, and the river grew yellower and muddier by the minute. I felt sure that the dancers would not be out on a night like this, and yet I could not sit still. Two and three times I went down to the bath, and came restlessly back to my room again.

Then, distant in the rain, I heard the slow beating of a drum. I tore open the shutters as if to wrench them from their grooves and leaned out the window. The drum beat seemed to be coming nearer. The rain, driven by a strong wind, lashed at my head. I closed my eyes and tried to concentrate on the drum, on where it might be, whether it could be coming this way. Presently I heard a samisen, and now and then a woman's voice calling to someone, a loud burst of laughter. The dancers had been called to a party in the restaurant across from their inn, it seemed. I could distinguish two or three women's voices and three or four men's voices. Soon they will be finished there, I told myself, and they will come here. The party seemed to go beyond the harmlessly gay and to approach the rowdy. A shrill woman's voice came across the darkness like the crack of a whip. I sat rigid, more and more on edge, staring out through the open shutters. At each drum beat I felt a surge of relief. "Ah, she's still there. Still there and playing the drum." And each time the beating stopped the silence seemed intolerable. It was as though I were being borne under by the driving rain.

For a time there was a confusion of footsteps—were they playing tag, were they dancing? And then complete silence. I glared into the darkness. What would she be doing, who would be with her the rest of the night?

I closed the shutters and got into bed. My chest was painfully tight. I went down to the bath again and splashed about violently. The rain stopped, the moon came out; the autumn sky, washed by the rain, shone crystalline into the distance. I thought for a moment of running out barefoot to look for her. It was after two.

III

THE man came by my inn at nine the next morning. I had just gotten up, and I invited him along for a bath. Below the bath-house the river, high from the rain, flowed warm in the South Izu autumn sun. My anguish of last night no longer seemed very real. I wanted even so to hear what had happened.

"That was a lively party you had last night."

"You could hear us?"

"I certainly could."

"Natives. They make a lot of noise, but there's not much to them really."

He seemed to consider the event quite routine, and I said no more.

"Look. They've come for a bath, over there across the river. Damned if they haven't seen us. Look at them laugh." He pointed over at the public bath, where six or seven naked figures showed through the steam.

One small figure ran out into the sunlight and stood for a moment at the edge of the platform calling something to us, arms raised as though for a plunge into the river. It was the little dancer. I looked at her, at the young legs, at the sculptured white body, and suddenly a draught of fresh water seemed to wash over my heart. I laughed happily. She was a child, a mere child, a child who could run out naked into the sun and stand there on her tiptoes in her delight at seeing a friend. I laughed on, a soft, happy laugh. It was as though a layer of dust had been cleared from my head. And I laughed on and on. It was because of her too-rich hair that she had seemed older, and because she was dressed like a girl of fifteen or sixteen. I had made an extraordinary mistake indeed.

We were back in my room when the older of the two young women came to look at the flowers in the garden. The little dancer followed her halfway across the bridge. The old woman came out of the bath frowning. The dancer shrugged her shoulders and ran back, laughing as if to say that she would be scolded if she came any nearer. The older young woman came up to the bridge.

Other books

The Rocks Below by Nigel Bird

Necessary Evil by Killarney Traynor

Old Wounds by Vicki Lane

Unknown by Unknown

Bro on the Go by Stinson, Barney

Blood Is a Stranger by Roland Perry

OBSESSED WITH TAYLOR JAMES by Toye Lawson Brown

When Lust Rules by Cavanaugh, Virginia

A Questionable Shape by Bennett Sims

Big-Top Scooby by Kate Howard