The Italian Renaissance (39 page)

Read The Italian Renaissance Online

Authors: Peter Burke

Autobiographies are not the only evidence for the self-consciousness of Renaissance Italians. There are also paintings. Portraits were often hung in family groups and commissioned for family reasons, but self-portraits are another matter. Most of them are not pictures in their own right but representations of the artist in the corner of a painting devoted to something else, such as the figure of Benozzo Gozzoli in his fresco of the procession of the Magi, Pinturicchio in the background to his

Annunciation

(Plate 8.2) or Raphael in his

School of Athens

. In the course of the sixteenth century, however, we find self-portraits in the strict sense by Parmigianino, for example, and Vasari, and more than one by Titian. They remind us of the importance of the mirrors manufactured in this period, in Venice in particular. Mirrors may well have encouraged self-awareness. As the Florentine writer Giambattista Gelli put it in a Carnival song he wrote for the mirror-makers of Florence, ‘A mirror allows one to see one’s own defects, which are not as easy to see as those of others.’

76

Even letters from clients to patrons have been analysed as evidence of the gradual emergence of a new sense of self as ‘an autonomous, discreet and elusive agent’.

77

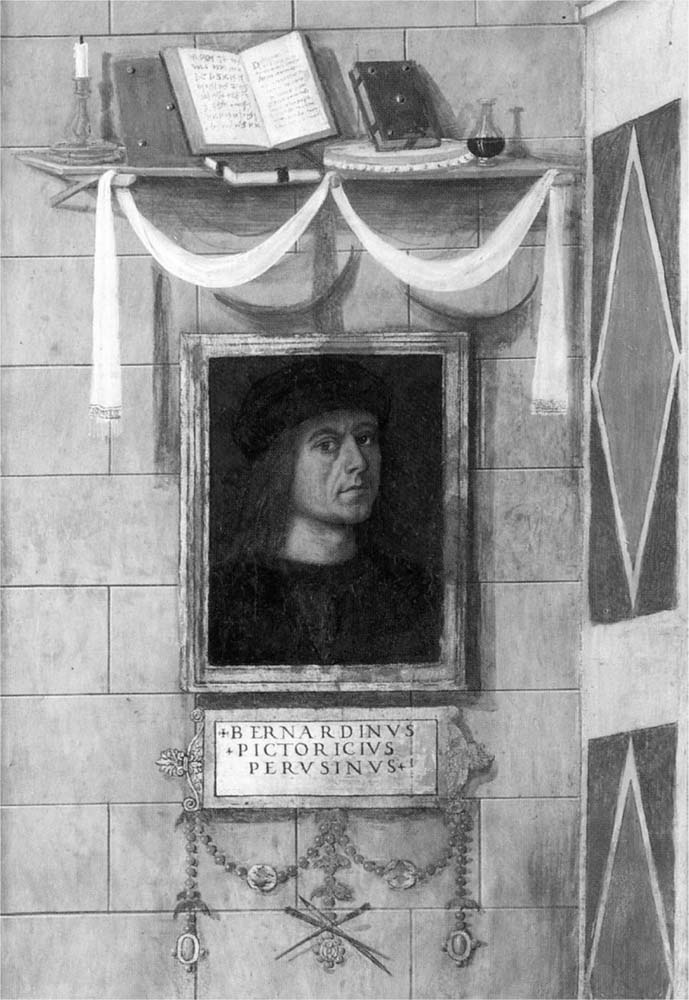

P

LATE

8.2 P

INTURICCHIO

:

S

ELF

-P

ORTRAIT

(

DETAIL FROM

T

HE

A

NNUNCIATION

)

Evidence of

self-awareness is also provided by the conduct books, of which the most famous are Castiglione’s

Courtier

(1528), Giovanni Della Casa’s

Galateo

(1558) and the

Civil Conversation

of Stefano Guazzo (1574). All three are manuals for the ‘presentation of self in everyday life’, as the sociologist Erving Goffman put it – instructions in the art of playing one’s social role gracefully in public. They inculcate conformity to a code of good manners rather than the expression of a personal style of behaviour, but they are nothing if not self-conscious themselves, and they encourage self-consciousness in the reader. Castiglione recommends a certain ‘negligence’ (

sprezzatura

), to show that ‘whatever is said or done has been done without pains and virtually without thought’, but he admits that this kind of spontaneity has to be rehearsed. It is the art which conceals art, and he goes on to compare the courtier to a painter. The ‘grace’ (

grazia

) with which he was so much concerned was, as we have seen, a central concept in the art criticism of his time. It is hard to decide whether to call Castiglione a painter among courtiers or his friend Raphael a courtier among painters, but the connections between their two domains are clear enough. The parallel was clear to Giovanni Pico della Mirandola in his famous

Oration on the Dignity of Man

, in which he has God say to man that, ‘as though the maker or moulder of thyself, thou mayest fashion thyself in whatever shape thou shalt prefer.’

78

The dignity of man was a favourite topic for writers on the ‘human condition’ (the phrase is theirs:

humana conditio

). It is tempting to take Pico’s treatise on the dignity of man to symbolize the Renaissance, and to contrast it with Pope Innocent III’s treatise on the misery of man as a symbol of the Middle Ages. However, both the dignity and the misery of man were recognized by writers in both Middle Ages and Renaissance. Many of the arguments for the dignity of man (the beauty of the human body, its upright posture, and so on) are commonplaces of the medieval as well as the classical and Renaissance traditions. The themes of dignity and misery were considered as complementary rather than contradictory.

79

All the same, there does appear to have been a change of emphasis revealing an increasing confidence in man in intellectual circles in the period. Lorenzo Valla, with characteristic boldness, called the soul the ‘man-God’ (

homo Deus

) and wrote of the soul’s ascent to heaven in the language of a Roman triumph. Pietro Pomponazzi declared that those (few) men who had managed to achieve almost complete rationality deserved to be numbered among the gods. Adjectives such as ‘divine’ and ‘heroic’ were increasingly used to describe painters, princes and other mortals.

Alberti had called the ancients ‘divine’ and Poliziano had coupled Lorenzo de’Medici with Giovanni Pico as ‘heroes rather than men’, but it is only in the sixteenth century that this heroic language became commonplace. Vasari, for example, described Raphael as a ‘mortal god’ and wrote of the ‘heroes’ of the house of Medici. Matteo Bandello referred to the ‘heroic house of Gonzaga’ and to the ‘glorious heroine’ Isabella d’Este. Aretino, typically, called himself ‘divine’. The famous references to the ‘divine Michelangelo’ were in danger of devaluation by this inflation of the language of praise.

80

These ideas of the dignity (indeed divinity) of man had their effect on the arts. Where Pope Innocent III, for example, found the human body disgusting, Renaissance writers admired it, and the humanist Agostino Nifo went so far as to defend the proposition that ‘nothing ought to be called beautiful except man’. By ‘man’ he meant woman, and in particular Jeanne of Aragon. One might have expected paintings of the idealized human body in a society where such views were expressed. The derivation of architectural proportions from the human body (again, idealized) also depended on the assumption of human dignity. Again, at the same time that the term ‘heroic’ was being overworked in literature, we find the so-called grand manner dominant in art. If we wish to explain changes in artistic taste, we need to look at wider changes in worldviews.

Another image of man, common in the literature of the time, is that of a rational, calculating, prudent animal. ‘Reason’ (

ragione

) and ‘reasonable’ (

ragionevole

) are terms which recur, usually with overtones of approval. They are terms with a wide variety of meanings, but the idea of rationality is central. The verb

ragionare

meant ‘to talk’, but then speech was a sign of rationality which showed man’s superiority to animals. One meaning of

ragione

was ‘accounts’: merchants called their account books

libri della ragione

. Another meaning was ‘justice’: the

Palazzo della Ragione

in Padua was not so much a ‘Palace of Reason’ as a court of law. Justice involved calculation, as the classical and Renaissance image of the scales should remind us.

Ragione

also meant ‘proportion’ or ‘ratio’. A famous early definition of perspective, in the life of Brunelleschi attributed to Manetti, called it the science which sets down the differences of size in objects near and far

con ragione

, a phrase which can be (and has been) translated as either ‘rationally’ or ‘in proportion’.

The habit of calculation was central to Italian urban life. Numeracy was relatively widespread, taught at special ‘abacus schools’ in Florence and elsewhere. A fascination with precise figures is revealed in some thirteenth-century texts, notably the chronicle of Fra Salimbene of Parma and Bonvesino della Riva’s treatise on ‘The Big Things of Milan’, which

lists the city’s fountains, shops and shrines and calculates the number of tons of corn the inhabitants of Milan demolished every day.

81

The evidence for this numerate mentality is even richer in the fourteenth century, as the statistics in Giovanni Villani’s chronicle of Florence bear eloquent witness, and richer still in the fifteenth and sixteenth century. In Florence and Venice in particular, an interest was taken in statistics of imports and exports, population and prices. Double-entry book-keeping was widespread. The great

catasto

of 1427, a household-to-household survey of a quarter of a million Tuscans who were then living under Florentine rule, both expressed and encouraged the rise of the numerate mentality.

82

Time was seen as something ‘precious’, which must be ‘spent’ carefully and not ‘wasted’; all these terms come from the third book of Alberti’s dialogue on the family. In similar fashion, Giovanni Rucellai advised his family to ‘be thrifty with time, for it is the most precious thing we have’.

83

Time could be the object of rational planning. The humanist schoolmaster Vittorino da Feltre drew up a timetable for the students. The sculptor Pomponio Gaurico boasted that since he was a boy he had planned his life so as not to waste it in idleness.

With this emphasis on reason, thrift (

masserizia

) and calculation went the regular use of such words as ‘prudent’ (

prudente

), ‘carefully’ (

pensatamente

) and ‘to foresee’ (

antevedere

). The reasonable is often identified with the useful, and a utilitarian approach is characteristic of a number of writers in this period. In Valla’s dialogue

On Pleasure

, for example, one of the speakers, the humanist Panormita, defends an ethic of utility (

utilitas

). All action – writes this fifteenth-century Jeremy Bentham – is based on calculations of pain and pleasure. Panormita may not represent the author’s point of view. What is relevant here, however, is what was thinkable in the period rather than who exactly thought it. This emphasis on the useful can be found again and again in texts of the period, from Alberti’s book on the family to Machiavelli’s

Prince

, with its references to the ‘utility of the subjects’ (

utilità de’sudditi

), and the need to make ‘good use’ of liberality, compassion and even cruelty. Again, Filarete created in his ideal city of Sforzinda a utilitarian utopia that Bentham would have appreciated, in which the death penalty has been abolished because criminals are more useful to the community if they do hard labour for life, in conditions exactly harsh enough for this punishment to act as an adequate deterrent.

84

Calculation affected human relationships. The account-book view of man is particularly clear in the reflections of Guicciardini. He advised his family:

Be careful not to do anyone the sort of favour that cannot be done without at the same time displeasing others. For injured men do not forget offences; in fact, they exaggerate them. Whereas the favoured party will either forget or will deem the favour smaller than it was. Therefore, other things being equal, you lose a great deal more than you gain.

85

Italians (adult males of the upper classes, at any rate) admitted a concern (unusual for other parts of Europe in the period, whatever may be true of the ‘age of capitalism’) with controlling themselves and manipulating others. In Alberti’s dialogue on the family, the humanist Lionardo suggests that it is good ‘to rule and control the passions of the soul’, while Guicciardini declared that there is greater pleasure in controlling one’s desires (

tenersi le voglie oneste

) than in satisfying them. If self-control is civilization, as the sociologist Norbert Elias suggests in his famous book

The Civilizing Process

, then even without their art and literature the Italians of the Renaissance would still have a good claim to be described as the most civilized people in Europe.

86

It is time to end this necessarily incomplete catalogue of the beliefs of Renaissance Italians and to try to see their worldview as a whole. One striking feature of this view is the coexistence of many traditional attitudes with others which would seem to be incompatible with them, a point that was famously made by Aby Warburg in his discussion of the last will and testament of the Florentine merchant Francesco Sassetti.

87

Generally speaking, Renaissance Italians, including the elites who dominate this book, lived in a mental universe which, like that of their medieval ancestors, was animate rather than mechanical, moralized rather than neutral, and organized in terms of correspondences rather than causes.

A common phrase of the period was that the world is ‘an animal’. Leonardo developed this idea in a traditional way when he wrote: ‘We can say that the earth has a vegetative soul, and that its flesh is the land, its bones are the structure of the rocks … its blood is the pools of water … its

breathing and its pulses are the ebb and flow of the sea.’

88

The operations of the universe were personified. Dante’s phrase about ‘the love that moves the sun and the other stars’ was still taken literally. Magnetism was described in similar terms. In the

Dialogues on Love

(1535) by the Jewish physician Leone Ebreo, a work in the neo-Platonic tradition of Ficino, one speaker explains that ‘the magnet is loved so greatly by the iron, that notwithstanding the size and weight of the iron, it moves and goes to find it.’

89

The discussions of the ‘body politic’ (above, p. 000) fit into this general picture. ‘Every republic is like a natural body’, as the Florentine theorist Donato Giannotti put it. Writers on architecture draw similar analogies between buildings and animate beings, analogies that are now generally misread as mere metaphors. Alberti wrote that a building is ‘like an animal’, and Filarete that ‘A building … wants to be nourished and looked after, and through lack of this it sickens and dies like a man.’ Michelangelo went so far as to say that whoever ‘is not a good master of the figure and likewise of anatomy’ cannot understand anything of architecture because the different parts of a building ‘derive from human members’.

90

Not even Frank Lloyd Wright in the twentieth century could match this organic theory of architecture.