The Italian Girl (18 page)

Authors: Iris Murdoch

‘Well – Sit down, Edmund, will you, you block all the light when you stand up. How hot it is in here – quite Mediterranean weather. And do tuck your long legs out of the way. I’ve got something to tell you, actually, something rather wonderful.’

‘What?’

‘I’m pregnant.’

She moved into the beam of sunlight and the golden dust seemed to settle on her face and her hair. She smiled at me through a gilded haze. I stared in confused amazement, not yet sure what to feel. ‘David?’

‘Yes, of course. Isn’t it splendid?’ She laughed with a laugh of sheer joy.

‘Oh, Isabel – if you’re glad I’m glad, very glad. Does David know – or Otto –?’

‘No. I shan’t tell anyone but you. This is really my business.’

‘Are you sure –?’

‘Yes. Now at last I have a future, I possess a future, it’s

here.

I’ve never really owned my life. I shall be independent,

we

shall be independent, now.’

‘A child,’ I said. ‘How strange. It makes everything seem different. A half-Jewish child.’

‘A half-Scottish child.’

‘A half-Russian child. A Lermontov. Oh, Isabel, I’m so glad.’

‘My child. As Flora never was. He will be mine, absolutely mine.’

Something worried me here. ‘Well, he’ll need, you know – especially if he’s a boy –’

‘A man around? Yes, I know. Edmund, you wouldn’t think of marrying me, would you? I’ve always liked you so much. Ever since the Learmont conversation.’

‘I’m sorry – I can’t – really I’m most touched, most grateful – but – well, you see there’s someone else.’

‘Someone else. You are a rum, mysterious fellow, Edmund. All right, all right, don’t blush so, though I must say it makes you look most attractive with the remains of that black eye, a sort of wine-stained effect. And, don’t worry about me and for heavens sake don’t start apologizing!’

‘I am so sorry, Isabel. But you know I’ll always be there if you need me, you and young Lermontov.’

‘I know. Uncle Edmund –

In loco parentis.

All that.’

‘All that. Good-bye, darling Isabel.’

The kitchen was empty with a disconcertingly final sort of emptiness. The clock had stopped. The fire was out. The dresser was bare. Everything was put away and the cupboards closed and locked. The hot sun blazed through the William Morris curtains, which were half drawn, making them glow like stained glass. The place was scrubbed, naked, abandoned, like a room awaiting a new tenant. The emptiness frightened me. I went softly and quickly through to the stairs. The sunshine did not penetrate here and the shaft of the house went up, dark and sullen, still smelling of fire. I listened to the silence of it.

I ran up the stairs. The landing was littered with charred remains of furniture out of Isabel’s room. I hesitated. I was a man pursued with only one place to go. I ran up the second flight of stairs to the attic floor where the Italian girl had always lived. I knocked on a door and entered into the dazzling sun.

My relief at finding her still there was so intense it was like the cutting of a cord in me and I almost stumbled, A closed suitcase lay on top of a well-roped trunk. The little white room with its rose-spotted wallpaper had been stripped and tidied. There only remained upon the wall the big familiar map of Italy that Carlotta had pinned up there very many years ago. I entered slowly.

She was standing by the window lost in the sunlight. ‘I’m sorry to rush in. I thought for a moment you’d gone.’

She said nothing, but moved a little. The dusty gauzy beam of light made a barrier between us. I began again incoherently. ‘I’m sorry –’

‘You came to say good-bye? That was kind of you.’ Her voice was dry, slightly rusty, accentless, a homeless disturbing voice.

I wanted to see her properly and edged round away from the sun. The beam of light fell across her breast and above it I saw the pale bony large-eyed face and the cap of dry glossy black hair. It was an old face, a new face, a boy by Titian, the maid of my childhood.

‘Well, yes, I –’ I felt like a man under a dreadful judgement in a foreign land. I could only stare and supplicate.

‘As you see, I am going too, though not just yet. You are catching the afternoon train? There is not much time.’ The voice was level, almost cruel, but the eyes seemed to get larger and larger.

‘No, I mean I don’t know – May I –?’ I looked desperately about. There was a dish of apples on the window-sill. ‘May I have one of these?’

She handed the dish in silence. I took the apple, but could not have eaten it. I would have choked. I fumbled it awkwardly against my waistcoat.

‘You are going – home?’

‘I am going back to Italy, yes. And you are going home too?’

‘Yes.’

‘I wish you a good journey.’

I was silent, I could not look at her now, the sense of the cruelty was too great. In another moment I felt I should be saying ‘Well, good-bye’, and leaving her alone forever in the sunlight. I felt like the poor machine I had just accused myself of being. Some pattern too strong for me was taking me away, curving away back to the old lonely places. I put the apple in my pocket.

Her cotton dress was blue with some kind of white design upon it, a straight simple dress. I looked at the bosom, I looked at the hem, I looked at the design stupefied. ‘ Well, I just wanted –’ I looked up at her face. It was vacant and merciless as an executioner’s. ‘Well, I just wanted to see if there was anything –’

‘Anything you could do for me? No, thank you.’

‘Oh, stop it, Maggie!’

‘Stop what?’

The repetition of the words shot me through with a sort of dry anguish, a sense of my futility. I felt powerless, weightless, paralysed like a man in a dream.

I said mumbling, ‘I’m sorry, I’m very stupid. I must be tired. I’ll leave you to pack. I suppose I must catch that train.’ The old pattern took hold of me, it herded me along like a brute, I started to shamble wretchedly towards the door.

I trod awkwardly on something which was out in the middle of the floor. It was a pair of white shoes. Grunting apologies I stooped to set them upright again, and then rose slowly holding one of them in my hand. Like a man in a fairy tale who is given an obscure sign I held on to the shoe with a sudden blind attention, not yet sure what I was being told.

I said slowly, ‘But these were the shoes you lost in the wood, weren’t they? So you found them again after all?’

She darted at me and almost wrenched the shoe out of my hand and tossed it on to the bed. It was like an attack. ‘I didn’t find them, I never lost them.’

The shock of her movement and her sudden proximity took the sense out of her words for a moment. ‘How do you mean, you never lost them?’

‘They were never lost. They were in my pocket. Now, good-bye Edmund. It is time for your train. Good-bye, good-bye –’

I picked up the shoe again. I sat down heavily upon the bed. I said, ‘I’m not going.’

There was a long but utterly different silence. The room moved like a kaleidoscope and settled down again, larger, enclosed, safe. I said, ‘Maria.’

That was the word which the Italian girl had uttered as we came out of the wood together on that day which now seemed so long ago. It was a charm which had been given me for a later use. My tongue was freed to use it now.

She came and sat at the other end of the bed and we gazed at each other. I could not remember that I had looked at anyone in quite that way before: when one is all vision and the other face enters into one’s own. I was aware too of a bodily feeling which was not exactly desire but was rather something to do with time, a sense of the present being infinitely large.

She did not smile, but the severe mask was changed, softened into a sort of rueful relieved exhaustion. She looked suddenly relaxed and very tired like someone who has travelled a long way and arrived.

She said, ‘I was not very clever with you, was I?’

Her words stirred me and touched me so poignantly that I could have moaned over them. But I said calmly, ‘You were certainly very harsh with me just now. Would you really have let me go away?’

She looked at me intently for a moment and then shook her head.

I hid my face against the shoe. Gratitude came as a physical pain, and then I too felt a relaxed tiredness which was a pure joy.

She went on, ‘I found I couldn’t talk to you and yet I knew that once I started it would be quite easy. Yet I couldn’t stop being awkward and hostile and making you awkward too.’ She spoke it with an air of simple explanation.

I said in the same tone, ‘I know. I think I was very stupid. But I would not have gone away.’

‘You might have done. You may yet. I just wanted us to be present to each other for a moment.’

‘We are certainly that.’ I felt a calm blissful sense of power which was at the same time a frenzy of humility. I was released and armed. Now I could act humanly, think, wish, reflect, speak. I gripped the shoe in my hand. I wanted to kneel on the floor. But I said coolly, ‘Why did you decide to let us see the will?’

‘I had to make you notice me somehow!’

I bowed my head. ‘I am a crude object!’ It was true. The money had certainly attracted my attention. But of course I had known all along. Or had I?

‘Then I nearly gave up because of her.’

‘Lydia?’

‘Elsa.’

The two names composed a shadowy presence, as if we had looked up to find ourselves close to some great tower. I said, ‘You mean when Elsa died it took away all purposes?’

‘Yes. But perhaps in the end it simply changed us into ourselves. We all died for a moment, but then what came after had a greater certainty.’

It seemed odd to me that she should speak of dying with Elsa. We were indeed, like all human beings, brief mourners. But what about Lydia? I was about to speak of her, but checked myself. That would come later, much later. How was I so sure that there was so much future? I said, ‘I think Otto has died for more than a moment.’

I recalled Otto’s crazy destroyed face. And then I suddenly apprehended myself at a parting of the ways. It was not yet too late. Flora had called my life a crippled life. Was that the truth of it? Ought I not now to jump up and run from the room before I should have meddled decisively, catastrophically, with myself? Some great force was poised, not yet released. This obscure allusive conversation could be terminated as abruptly as it had started. I could still go away down the stairs and out of the house. Ought I not to return to my solitude and my simplicities and study once more to gain by patience what had come, perhaps, to Otto in a moment of flame? Otto and I had in some sense changed places, passing each other on the way, and now it was I who had the fool’s part. What was the value, what had been the value, of my long meditation? I had had no power here to heal the ills of others, I had merely discovered my own. I had thought to have passed beyond life, but now it seemed to me that I had simply evaded it. I had not passed beyond anything; I was a false religious, a frightened man.

It was only for a second that I saw her as a temptress. At the next moment her face was the face of happiness, something which I had scarcely ever seen and which I had long ago stopped seeking. And even as I apprehended her as my happiness I apprehended her too as my unhappiness. I recalled David’s words, that one must suffer in one’s own place. Whatever joy or sorrow might come to me from this would be real and my own, I would be living at my own level and suffering in my own place. There was only one person in the world for whom I could be complete and I had found her. And with that of course I thought of Lydia and of Lydia’s mystery which I was now in some sense inheriting, and I knew that at some time in the future the Italian girl would speak to me Lydia’s true epitaph.

I rubbed my eyes. I did not want to have, yet, so many thoughts. I wanted to be, for a while, perhaps for the first time, diminished and simple, and to deal simply for better or worse with another person. I saw her now, a girl, a stranger, and yet the most familiar person in the world: my Italian girl, and yet also the first woman, as strange as Eve to the dazed awakening Adam. She was there, separately and authoritatively there, like the cat which Isabel had shown me from the window. The fleeing woman fled no longer, she had turned about.

I said, ‘It’s odd, I scarcely know you. Yet I feel now for the first time that my past is really continuous with my future. Were you really there

then,

was it really you?’

She smiled at last and patted back the short hair to which she had not yet got accustomed. ‘You were so very beautiful, Edmund, when you were seventeen.’

I gave a sort of groan. ‘But now, what am I now?’ I scarcely knew what I looked like any more. I had no images of myself. That too I would have to learn.

‘

Si vedra. Non aver paura.’

The Italian words were like a transforming bell. I felt suddenly the heat of the room, the sweet presence of the sun: to live in the sun, to love in the open. I said, ‘You are going to Italy?’

‘Yes – to Rome.’

I took a deep breath. I was suddenly trembling violently. ‘May I drive you there in my car?’

Her answer was a nod, a sigh. At the same time she put her finger to her lips.

I understood. I looked at her hands. They were still as distant as stars. I drew back. There was a time ahead.

I took the apple from my pocket and began to eat it. I said, ‘I’ll go and pack. Then we can think about times and places. Why, it’s Italian weather already.’

As I went to the door I paused beside the map of Italy. The route, yes, that too we would have to discuss. I drew my finger along the Via Aurelia. Genova, Pisa, Livorno, Grosseto, Civitavecchia, Roma.

Iris Murdoch (1919–1999) was one of the most influential British writers of the twentieth century. She wrote twenty-six novels over forty years, as well as plays, poetry, and works of philosophy. Heavily influenced by existentialist and moral philosophy, Murdoch’s novels were also notable for their rich characters, intellectual depth, and handling of controversial topics such as adultery and incest.

Born in Dublin, Ireland, Murdoch moved to London with her parents as a child. She attended Somerville College in Oxford where she studied classics, ancient history, and philosophy. While at Oxford, she was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (which she later left, disillusioned) and, in the 1940s, worked in Austrian and Belgian relief camps for the United Nations. After completing her postgraduate degree at Newnham College in Cambridge, she became a Fellow of St. Anne’s College, Oxford, where she lectured in philosophy for fifteen years.

In 1954, she published her first novel,

Under the Net

, about a struggling young writer in London, which the American Modern Library would later select as one of the one hundred best English-language novels of the twentieth century and

Time

magazine would list as among the twenty-five best novels since 1923. Two years after completing

Under the Net

, Murdoch married John Bayley, an English scholar at the University of Oxford and an author. In a 1994 interview, Murdoch described her relationship with Bayley as “the most important thing in my life.” Bayley’s memoir about their relationship,

Elegy for Iris

, was made into the major motion picture

Iris

, starring Judi Dench and Kate Winslet, in 2001.

For three decades, Murdoch published a new book almost every year, including historical fiction such as

The Red and the Green

, about the Easter Rebellion in 1916, and the philosophical play

Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues

. She was awarded the 1978 Booker Prize for

The Sea, The Sea

, won the Royal Society Literary Award in 1987, and was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1987 by Queen Elizabeth.

Her final years were clouded by a long struggle with Alzheimer’s before her passing in 1999.

Murdoch as an infant with her mother, Irene, in 1919. Irene was a trained opera singer, though she gave it up after Iris was born. Murdoch’s father, John, worked as a civil servant once the family moved to London.

Murdoch in 1923, at age three or four. She was an only child and remembered her childhood as “a perfect trinity of love.” Her father encouraged her to read at a young age and her favorite authors included Lewis Carroll and Robert Louis Stevenson.

The London house in which Murdoch grew up, seen here in 1926.

Murdoch in 1935. She was studying philosophy, classics, and ancient history at Oxford at the time of this photo.

Murdoch with an unidentified friend in 1946. At this time Murdoch was studying philosophy at Cambridge, where she enrolled after working for the United Nations to help Europeans displaced by the Second World War.

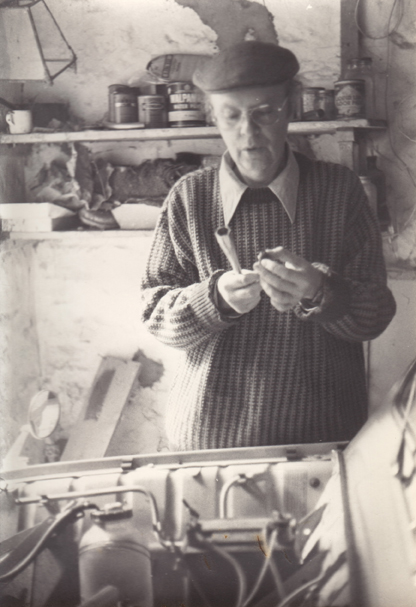

John Bayley, Murdoch’s husband, in the 1960s. The two were married in 1956 after meeting at Oxford.

Murdoch and Bayley at an unknown date. One of the couple’s shared passions was swimming, which they did together whenever the opportunity presented itself.

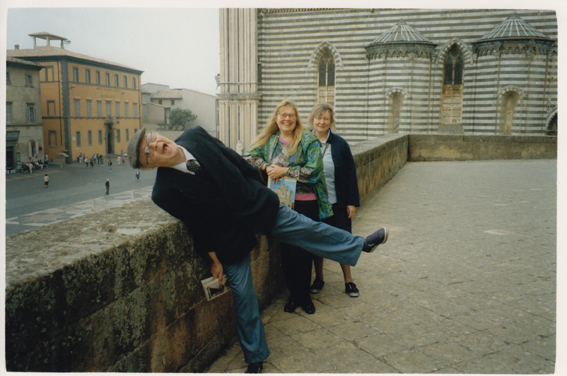

Bayley and Murdoch on vacation in Orvieto, Italy, in September 1988, with family friend Audi Villers, whom Bayley married after Murdoch’s death.

Bayley and Murdoch in Delft, Holland, in 1996. Murdoch was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in the mid-1990s.

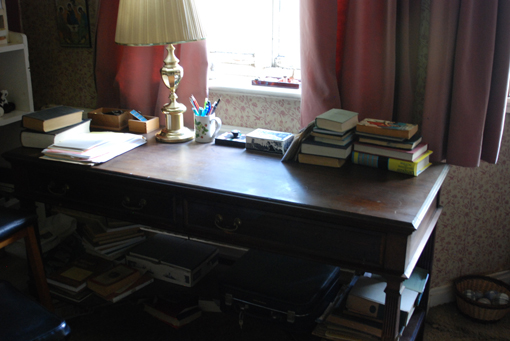

Bayley’s writing desk, which originally belonged to J.R.R. Tolkien. Murdoch’s scrapbook can be seen atop the desk.