The Italian Boy (2 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Covent Garden, lying west of the City, was a half-poor, half-prosperous area between the Strand and the dreadful slum area of St. Giles.

Just to the northeast of Covent Garden, Holborn was an area of similarly mixed levels of prosperity, and parts of it were called “Little Italy” because of the many Italian immigrants who settled there.

Although both Covent Garden and Holborn are to the west of the City, neither counts as the West End, which is the term applied to the wealthier areas slightly farther west, such as Regent Street, Oxford Street, Hanover Square, and Mayfair.

Smithfield is just inside the City border, at its western edge; it was notorious for the filth, noise, and commotion caused by its famous live-meat market.

Bethnal Green in 1831 was a desperately poor working-class area to the northeast of the City.

Spitalfields, Whitechapel, and Shoreditch, which were once equally poor eastern districts, lie to the south of Bethnal Green.

The Elephant and Castle, another area that, like Covent Garden, contained a population with mixed fortunes, is one mile south of the Thames.

The Borough—site of the United Hospitals of St. Thomas’s and Guy’s, plus the Webb Street private anatomical school—is just over London Bridge on the south bank of the Thames.

Currency Conversion

One guinea | | =21 shillings | | =252 pennies (d) |

One pound | | =20 shillings | | =240d |

One crown | | =5 shillings | | =60d |

Half a crown | | =2 shillings and 6d | | =30d |

One florin/guilder | | =2 shillings | | =24d |

One shilling (bob) | | | =12d | |

One farthing | | | =¼d |

London Prices, Early 1830s

Hackney cab fare, Old Bailey to Shoreditch Church (1½ miles) | | 2 shillings |

Glass/pint of Blue Ruin gin | | 3d/1 shilling |

Glass/pint of cheap gin | | 2d/10d |

A quarter loaf of bread | | 9d |

A pint of porter | | 2d |

10 lbs. potatoes | | 4d |

Charles Dickens’s weekly factory wage as a twelve-year-old in 1824 | | 6–7 shillings (15–16 guineas/year) |

Weekly wage of an East End silk weaver in 1831 (twelve-hour day) | | 5–7 shillings (12–16 guineas/year) |

A well-paid workingman’s yearly salary | | 75–80 guineas |

A well-paid manservant’s weekly salary | | 1 guinea (50–55 guineas/year) |

Starting weekly salary for New Police constables | | 1 guinea (50–55 guineas/year) |

Average cost of an Old Bailey prosecution | | £3 10s |

Average cost of a fresh corpse in 1831 | | 8–12 guineas |

ONE

Suspiciously Fresh

George Beaman, surgeon to the parish of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, turned back the scalp of the corpse lying before him. Beneath the skin he observed coagulated blood, and, peeling away the flesh along the length of the neck, he saw similar minor hemorrhages at the top of the spinal column. He concluded that death had been caused by a sharp blow to the back of the neck.

The body was that of a boy of around fourteen years of age, four feet six inches in height, with fair hair and gray eyes that were bloodshot and bulging. Blood oozed from an inch-long wound on his left temple, and his toothless gums were dripping blood. At the time of his killing, a meal—which had included potatoes and a quantity of rum—was being digested. A large, powerful hand had grasped the boy on his left forearm—black bruises from the finger marks were plainly visible—and earth or clay had been smeared across the torso and thighs. The chest appeared to have caved in slightly, as though someone had knelt on it. The heart contained scarcely any blood, which Beaman took to indicate a very sudden death, but all the other organs were found to have been unremarkable and perfectly healthy. The most perplexing thing about the corpse was its freshness: it had been alive three days earlier, Beaman felt sure; and it was also clear to the surgeon that despite the bits of earth and clay, this body had never been buried, had never even been laid out in preparation for burial—and yet it had been delivered to King’s College’s anatomy department as a Subject for medical students to dissect.

It was late evening, Sunday, 6 November 1831, and Beaman was anatomizing the corpse in the tiny watch house in the graveyard of St. Paul’s Church, Covent Garden, at the request of local magistrates. He and a number of fellow surgeons had been probing and exploring the body in the first-floor room since early afternoon. A sunny winter’s day had turned into a chilly evening by the time the medical men had made up their mind about the cause of death. As Beaman and his colleagues left, two young trainees, by now feeling faint with tiredness and nausea, stayed in the cold, stuffy room to sew up the corpse. Working alongside Beaman had been Herbert Mayo and Richard Partridge, respectively professor and “demonstrator,” or lecturer, of anatomy at King’s College, just a few streets away in the Strand. The day before, Partridge had sent for the police when one of the body-snatching gangs that supplied disinterred corpses to medical schools had tipped this body out of a sack and onto the stone floor of the dissecting room at King’s. It had looked suspiciously fresh. Partridge tricked the body snatchers into waiting at King’s while police officers were summoned, and at three o’clock in the afternoon, John Bishop, James May, and Thomas Williams were arrested on suspicion of murder, along with Michael Shields, a porter who had carried the body.

* * *

Earlier that day,

worried parents of missing sons had been admitted to the watch house to view the body, having read a description of the boy circulated in police handbills and notices posted on walls, doors, and windows throughout the parish. Among the visitors had been several Italians. Signor Francis Bernasconi of Great Russell Street, Covent Garden, “plasterer to His Majesty,” had wondered whether the deceased was a boy from Genoa who had made his living as an “image boy”—hawking wax or plaster busts of the great and the good, past and present, about the streets of London. Bernasconi was a plaster figurine maker, or

figurinaio,

and he employed a number of Italian child immigrants to advertise and sell his wares in this way. Another figurinaio said that the dead boy had sometimes helped paint the plaster figures and that his “master” had left England at the end of September. The minister at the Italian Chapel in Oxenden Street, off the Haymarket, claimed that the boy had been a member of his congregation but was unable to name him. Two more Italians identified the dead boy as an Italian beggar who walked the streets carrying a tortoise that he exhibited in the hope of receiving a few pennies, while Joseph and Mary Paragalli of Parker Street, Covent Garden, said the boy was an Italian who wandered the West End exhibiting white mice in a cage suspended around his neck. (Joseph was a street musician, playing barrel organ and panpipes.) The Paragallis had known the child for about a year, they said, but neither of them suggested a name for him. Mary Paragalli claimed she had last seen him alive shortly after noon on Tuesday, 1 November, in Oxford Street, near Hanover Square.

Charles Starbuck, a stockbroker, came forward to tell the Bow Street police officers that he believed the boy was an Italian beggar who was often to be seen near the Bank of England exhibiting white mice in a cage; Starbuck had viewed the body and was in “no doubt” about its being the same child. He had seen the boy looking tired and ill, sitting with his head sunk almost to his lap, on the evening of Thursday, 3 November, between half past six and eight o’clock. Starbuck was walking with his brother near the Bank and said, “I think he is unwell,” but his brother replied, “I think he’s a humbug. I’ve often seen him in that position.” A crowd gathered round, concerned at the boy’s condition, and one youth told the boy he ought to move on as police officers were heading that way. The Starbucks walked on. But on Wednesday the ninth, three days after viewing the body, Charles Starbuck wrote to the coroner to say that he had subsequently seen this boy near the Bank, and retracted his identification.

The newspapers seized on the possible Italian connection remarkably swiftly. As the coroner’s hearing began on 8 November, the

Times

referred to the proceedings as “The Inquest on the Italian Boy,” when no such identity had been confirmed. In fact, the

Times

reporter seems to have been quite carried away with emotion by the death of “the poor little fellow who used to go about the streets hugging a live tortoise, and soliciting, with a smiling countenance, in broken English and Italian, a few coppers for the use of himself and his dumb friend.” The report continued: “We saw the body last night, and were struck with its fine healthy appearance.… The countenance of the boy does not exhibit the least contortion, but, on the contrary, wears the repose of sleep, and the same open and good-humoured expression which marked the features in life is still discernible.”

1

This was a fantastical statement, since only someone able to give a positive identification could possibly know how the child had looked when alive. The following day, the

Times

thundered, in an extraordinary editorial: “If it shall be proved that he was murdered, for the purpose of deriving a horrible livelihood from the disposal of his body—if wretches have picked up from our streets an unprotected foreign child, and prepared him for the dissecting knife by assassination—if they have prowled about in order to obtain Subjects for a dissecting-room—then we may be assured that this is not a solitary crime of its kind.”

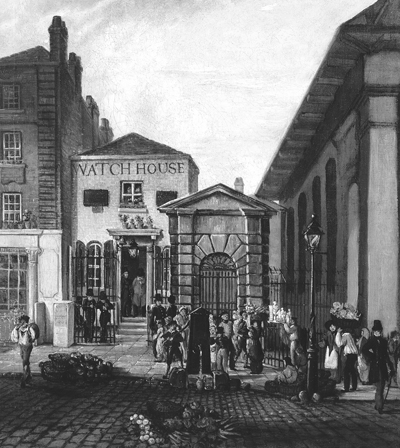

An Italian boy, or image boy, from J. T. Smith’s

Etchings of Remarkable Beggars,

1815

In such a way, rumor was being reported as fact—a matter that was not lost on the coroner’s jury. “We are proceeding in the dark,” complained a member of the jury. The hearing was under way at the Unicorn, a public house in Covent Garden that backed onto St. Paul’s watch house. It appeared to the jury that no one in authority was able to rebut or confirm the various speculations about the identity of the dead boy. How, the jury asked, can we be expected to arrive at a verdict when we don’t even know who has died? And to make matters worse, as soon as any goings-on at hospitals were mentioned or any surgeon looked likely to be named, the coroner and the parish clerk of St. Paul’s would go into a huddle to discuss whether the inquest should continue or be adjourned.

The jury’s exasperation compelled vestry clerk James Corder, who was overseeing the proceedings, to state that he understood “from inquiries he had made” that the dead boy was called Giacomo Montero, a beggar who had been brought to London a year earlier by an Italian named Pietro Massa, who lived in Liquorpond Street, in the area of Holborn known colloquially as Little Italy.

2

But here Joseph Paragalli spoke up to say that he himself had made his own inquiries at the Home Office’s “Alien Office,” near Whitehall, and that the description held there of Montero did not fit the dead boy in the least. Perhaps then, said Corder, the boy had been Giovanni Balavezzolo, another Italian vagrant boy who was said to be missing from his usual haunts. To solve the problem, Corder suggested the jury simply return a verdict of willful murder against some person or persons unknown. The jury remained unconvinced.