The Island at the Center of the World

For my father

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not exist without the work of Charles Gehring, who, as director of the New Netherland Project, has devoted thirty years to translating the manuscript Dutch records of the New Netherland colony. But published translations aside, for more than two years he has welcomed me into his workspace, opened his files to me, offered advice, made introductions, and helped in dozens of other ways. Over Vietnamese lunches and pints of microbrew beer, on the Albany waterfront and along the canals of Amsterdam, he has been my guide. My greatest thanks to you, Charly.

I also owe a debt of gratitude to Janny Venema of the New Netherland Project, for similar help mixed with friendship. She spent days transcribing as-yet-unpublished manuscripts for me. She gave me a primer in how to read seventeenth-century Dutch handwriting. She made the town of Beverwyck, long since swallowed up by the city of Albany, come alive for me.

Of the many others who helped me, I would like to thank Jeremy Bangs and Carola de Muralt of the American Pilgrim Museum in Leiden, the Netherlands, who gave me a sense of the texture of seventeenth-century Dutch life and a magnificent afternoon-long tour of their one-of-a-kind museum. Patricia Bonomi, professor emeritus of history at New York University, offered guidance as I set out on the project and encouragement as I approached the end. Peter Christoph of the New York State Library shared with me his reminiscences about his discovery of the Dutch manuscripts and efforts to get them translated. Diane Dallal, archaeologist with New York Unearthed and the South Street Seaport Museum, helped me to visualize New Amsterdam amid the canyons of lower Manhattan. Firth Fabend, historian and author, helped on many fronts, especially in understanding how “Dutchness” changed in North America from the seventeenth century onward, and in assessing the colony's legacy. The Friends of New Netherland invited me to speak at their annual meeting in 2003, thus providing me a chance to air some of my ideas about the Dutch colony. Willem Frijhoff of the Free University of Amsterdam, distinguished historian and authority on New Netherland and its people, is a man of great generosity who offered brilliant, timely advice and encouraged me in my focus on Adriaen van der Donck. Elisabeth Paling Funk, Dutch-born scholar and authority on Washington Irving, helped me to disentangle history from myth, and translated some seventeenth-century poetry for me. Wayne Furman of the New York Public Library, as well as the staff of the library's New York History and Genealogy division, accommodated me throughout my research. I'm grateful to Joyce Goodfriend of the University of Denver, authority on early New York, for good conversation on history and historians, for advice and pointers, and for introducing me to Jack's Oyster House in Albany. Anne Halpern of the National Gallery of Art assisted with research on the portrait of Adriaen van der Donck. Leo Hershkowitz, professor of history at Queens College, who has written with equal elegance about both the Jews of New Amsterdam and Boss Tweed, knows New York history as few people on earth do, and gave me the benefit of his perspective. Maria Holden, conservator at the New York State Archives, gave me a primer on the Dutch documents as artifacts: on paper, ink, and methods of preservation.

On a sun-dazzled Fourth of July morning on the terrace of the Stadscafe in the city of Leiden, Jaap Jacobs of the University of Amsterdam broadened my view of seventeenth-century American colonial history, helping me to see it not merely as foreshadowing later American history but as part of European history and the global power struggle between England and the Dutch Republic; I am also grateful for his elegant writings on New Netherland and on the concept of tolerance in the seventeenth century, and for conversation on the prickly figure of Peter Stuyvesant, a biography of whom he is currently at work on. My thanks to Joep de Koning, probably the world's foremost collector of maps of New Netherland, for conversation, for insights, and for giving me a chance to roam among his one-of-a-kind collection; to Dennis Maika of Fox Lane High School, Bedford, New York, whose dissertation on and insights into the significance of the 1653 municipal charter and the subsequent boom in the colony were instrumental in shaping my own thoughts; to Simon Middleton of the University of East Anglia, for pointers on early modern Republicanism in the Netherlands and for his encouragement as a fellow Van der Donck enthusiast; to Peter Neil, director of the South Street Seaport Museum; to Chip Reynolds, skipper of the

Half Moon,

for taking me aboard and giving me a feel of the ship; to Peter Rose, authority on seventeenth-century Dutch food, for culinary assistance; to Thomas Rosenbaum of the Rockefeller Archives, Pocantico Hills, New York, who afforded me access to that institution's remarkable collection of seventeenth-century Dutch notarial records; to Ada Louise Van Gastel, for her work on Adriaen van der Donck and her encouragement; to Hanny Veenendaal of the Netherlands Center in New York City, for giving me a grounding in the Dutch language and for assisting in translations and in reading old Dutch documents; to Greta Wagle, who welcomed me into the family of New Netherland aficionados, put me in touch with people, and has been generally delightful to know; to Gerald de Weerdt, curator of 't Behouden Huys Museum, Terschelling, the Netherlands, for sharing insights on Dutch seafaring; to Laurie Weinstein, Western Connecticut State University, who helped in my attempts to understand Dutch-English-Indian interactions; and to Thomas Wysmuller for discussions on Dutch history and for enthusiastic support.

A separate thank you to Firth Fabend, Charly Gehring, Leo Hershkowitz, Joep de Koning, Tim Paulson, Janny Venema, and Mark Zwonitzer for reading the manuscript and offering excellent comments and critiques. The book is greatly improved by their input, though of course any errors remain my own doing.

My thanks also to Coen Blaauw; José Brandão, Western Michigan University; Marilyn Douglas, New York State Library; Howard Funk; Dietrich Gehring; April Hatfield, Texas A&M University; L. J. Krizner, the New York Historical Society; Karen Ordahl Kupperman, New York University; Hubert de Leeuw; Harry Macy, editor of

The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record

; Richard Mooney,

New York Times

editorial board, retired; the staff of the New York State Library and Archives; Hennie Newhouse, Friends of New Netherland; Don Rittner; Martha Shattuck; Amanda Sutphin, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Martine Julia van Ittersum, Harvard University; Cynthia van Zandt, University of New Hampshire; Loet Velmans; David William Voorhees, of The Holland Society of New York and managing editor of

de Halve Maen

; Charles Wendell, Friends of New Netherland; and James Homer Williams, Middle Tennessee State University.

Thanks also to my team. Anne Edelstein, my agent and friend, plucked the rabbit of an idea out of my brain and made this all happen. Laura Williams gave advice in the early going, and Emilie Stewart assisted in the endgame. Anne Hollister and Elisabeth King fact checked the manuscript with scrupulosity and style. Tim Paulson listened to my initial rambling, inchoate idea, pushed me to carry it forward, and was there along the way with smart counsel. Bill Thomas, my editor at Doubleday, championed the project from the beginning and managed throughout to support it with the excellent combination of overflowing enthusiasm and sharp critical judgment. Thanks also to Kendra Harpster, John Fontana, and Christine Pride of Doubleday. In London, Marianne Velmans, my editor at Transworld, brought her Anglo-Dutch perspective to bear, and critiqued the manuscript with great insight.

Finally, my wife, Marnie Henricksson, endured the years of this project, shared the good times of it with me and saw me through what were some definite not-so-good times. She is the love of my life and I owe her everything.

So much for the living. From time to time during the course of my work on this book I've had the flickering sense that the spirits of Adriaen van der Donck and Peter Stuyvesant were hovering somewhere nearby, the first, perhaps, interested at the notion of being plucked from historical oblivion, the second maybe at potentially being rescued from the status of historical cartoon. There is one other spirit I've felt as well, a less obvious one. I would like to express my gratitude to the late Barbara W. Tuchman: for providing a model of a writer committed to history and narrative both; for being among the first popular historians to recognize, in her final book,

The First Salute,

the overlooked contribution of the Dutch to early American history; and finally and perhaps most importantly to me, for making a bequest to the New York Public Library in honor of her father, which resulted in the establishment of the Wertheim Study Room, where much of this book was researched.

Prologue

THE MISSING FLOOR

I

f you were to step inside an elevator in the lobby of the New York State Library in Albany, you would discover that, although the building has eleven floors, there is no button marked eight. To get to the eighth floor, which is closed to the public, you ride to seven, walk through a security door, state your business to a librarian at the desk, then go into another elevator and ride up one more flight.

As you pass shelves of quietly moldering books and periodicals—the budgets of the state of Kansas going back to 1923, the Australian census, the complete bound series of

Northern Miner—

you may be greeted by the sound of German opera coming from a small room at the southeast corner. Peering around the doorway, you would probably find a rather bearish-looking man hunched over a desk, perhaps squinting through an antique jeweler's loupe. The hiddenness of the location is an apt metaphor for the work going on here. What Dr. Charles Gehring is studying with such attention may be one of several thousand artifacts in his care—artifacts that, once they give up their secrets through his efforts, breathe life into a moment of history that has been largely ignored for three centuries.

This book tells the story of that moment in time. It is a story of high adventure set during the age of exploration—when Francis Drake, Henry Hudson, and Captain John Smith were expanding the boundaries of the world, and Shakespeare, Rembrandt, Galileo, Descartes, Mercator, Vermeer, Harvey, and Bacon were revolutionizing human thought and expression. It is a distinctly European tale, but also a vital piece of America's beginnings. It is the story of one of the original European colonies on America's shores, a colony that was eventually swallowed up by the others.

At the book's center is an island—a slender wilderness island at the edge of the known world. As the European powers sent off their navies and adventurer-businessmen to roam the seas in history's first truly global era, this island would become a fulcrum in the international power struggle, the key to control of a continent and a new world. This account encompasses the kings and generals who plotted for control of this piece of property, but at the story's heart is a humbler assemblage: a band of explorers, entrepreneurs, pirates, prostitutes, and assorted scalawags from different parts of Europe who sought riches on this wilderness island. Together, this unlikely group formed a new society. They were the first New Yorkers, the original European inhabitants of the island of Manhattan.

We are used to thinking of American beginnings as involving thirteen English colonies—to thinking of American history as an English root onto which, over time, the cultures of many other nations were grafted to create a new species of society that has become a multiethnic model for progressive societies around the world. But that isn't true. To talk of the thirteen original English colonies is to ignore another European colony, the one centered on Manhattan, which predated New York and whose history was all but erased when the English took it over.

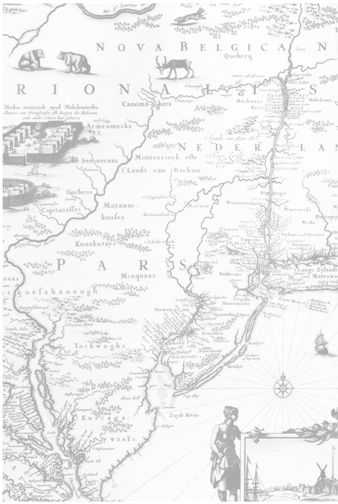

The settlement in question occupied the area between the newly forming English territories of Virginia and New England. It extended roughly from present-day Albany, New York, in the north to Delaware Bay in the south, comprising all or parts of what became New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. It was founded by the Dutch, who called it New Netherland, but half of its residents were from elsewhere. Its capital was a tiny collection of rough buildings perched on the edge of a limitless wilderness, but its muddy lanes and waterfront were prowled by a Babel of peoples—Norwegians, Germans, Italians, Jews, Africans (slaves and free), Walloons, Bohemians, Munsees, Montauks, Mohawks, and many others—all living on the rim of empire, struggling to find a way of being together, searching for a balance between chaos and order, liberty and oppression. Pirates, prostitutes, smugglers, and business sharks held sway in it. It was

Manhattan,

in other words, right from the start: a place unlike any other, either in the North American colonies or anywhere else.

Because of its geography, its population, and the fact that it was under the control of the Dutch (even then its parent city, Amsterdam, was the most liberal in Europe), this island city would become the first multiethnic, upwardly mobile society on America's shores, a prototype of the kind of society that would be duplicated throughout the country and around the world. It was no coincidence that on September 11, 2001, those who wished to make a symbolic attack on the center of American power chose the World Trade Center as their target. If what made America great was its ingenious openness to different cultures, then the small triangle of land at the southern tip of Manhattan Island is the New World birthplace of that idea, the spot where it first took shape. Many people—whether they live in the heartland or on Fifth Avenue—like to think of New York City as so wild and extreme in its cultural fusion that it's an anomaly in the United States, almost a foreign entity. This book offers an alternative view: that beneath the level of myth and politics and high ideals, down where real people live and interact, Manhattan is where America began.

The original European colony centered on Manhattan came to an end when England took it over in 1664, renaming it New York after James, the Duke of York, brother of King Charles II, and folding it into its other American colonies. As far as the earliest American historians were concerned, that date marked the true beginning of the history of the region. The Dutch-led colony was almost immediately considered inconsequential. When the time came to memorialize national origins, the English Pilgrims and Puritans of New England provided a better model. The Pilgrims' story was simpler, less messy, and had fewer pirates and prostitutes to explain away. It was easy enough to overlook the fact that the Puritans' flight to American shores to escape religious persecution led them, once established, to institute a brutally intolerant regime, a grim theocratic monoculture about as far removed as one can imagine from what the country was to become.

The few early books written about the Dutch settlement had a brackish odor—appropriately, since even their authors viewed the colony as a backwater, cut off from the main current of history. Washington Irving's “Knickerbocker” history of New York—a historical burlesque never intended by its author to be taken as fact—muddied any attempt to understand what had actually gone on in the Manhattan-based settlement. The colony was reduced by popular culture to a few random, floating facts: that it was once ruled by an ornery peg-legged governor and, most infamously, that the Dutch bought the island from the Indians for twenty-four-dollars' worth of household goods. Anyone who wondered about it beyond that may have surmised that the colony was too inept to keep records. As one historian put it, “Original sources of information concerning the early Dutch settlers of Manhattan Island are neither many nor rich [for] . . . the Dutch wrote very little, and on the whole their records are meager.”

Skip ahead, then, to a day in 1973, when a thirty-five-year-old scholar named Charles Gehring is led into a vault in the New York State Library in Albany and shown something that delights his eye as fully as a chest of emeralds would a pirate's. Gehring, a specialist in the Dutch language of the seventeenth century (an obscure topic in anyone's estimation), had just completed his doctoral dissertation. He was casting about for a relevant job, which he knew wouldn't be easy to find, when fate smiled on him. Some years earlier, Peter Christoph, curator of historical manuscripts at the library, had come across a vast collection of charred, mold-stippled papers stored in the archives. He knew what they were and that they comprised a vast resource for American prehistory. They had survived wars, fire, flooding, and centuries of neglect. Remarkably, he doubted he would be able to bring them into the light of day. There was little interest in what was still considered an odd backroad of history. He couldn't come up with funds to hire a translator. Besides that, few people in the world could decipher the writings.

Christoph eventually came in contact with an influential American of Dutch descent, a retired brigadier general with the excellent name of Cortlandt van Rensselaer Schuyler. Gen. Schuyler had recently overseen the building in Albany of Empire State Plaza, the central state government complex, for his friend, Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Schuyler put in a call to Rockefeller, who was by now out of office and about to be tapped by Gerald Ford as his vice president. Rockefeller made a few telephone calls, and a small amount of money was made available to begin the project. Christoph called Gehring and told him he had a job. So it was that while the nation was recovering from the midlife crisis of Watergate, a window onto the period of its birth began to open.

What Charles Gehring received into his care in 1974 was twelve thousand sheets of rag paper covered with the crabbed, loopy script of seventeenth-century Dutch, which to the untutored eye looks something like a cross between our Roman letters and Arabic or Thai—writing largely indecipherable today even to modern Dutch speakers. On these pages, in words written three hundred and fifty years ago in ink that has now partially faded into the brown of the decaying paper, an improbable gathering of Dutch, French, German, Swedish, Jewish, Polish, Danish, African, American Indian, and English characters comes to life. This repository of letters, deeds, wills, journal entries, council minutes, and court proceedings comprises the official records of the settlement that grew up following Henry Hudson's 1609 voyage up the river that bears his name. Here, in their own words, were the first Manhattanites. Deciphering and translating the documents, making them available to history, Dr. Gehring knew, was the task of a lifetime.

Twenty-six years later, Charles Gehring, now a sixty-one-year-old grandfather with a wry grin and a soothing, carmelly baritone, was still at it when I met him in 2000. He had produced sixteen volumes of translation, and had several more to go. For a long time he had labored in isolation, the “missing floor” of the state library building where he works serving as a nice metaphor for the way history has overlooked the Dutch period. But within the past several years, as the work has achieved a critical mass, Dr. Gehring and his collection of translations have become the center of a modest renaissance of scholarly interest in this colony. As I write, historians are drafting doctoral dissertations on the material and educational organizations are creating teaching guides for bringing the Dutch settlement into accounts of American colonial history.

Dr. Gehring is not the first to have attempted a translation of this archive. In fact, the long, bedraggled history of the records of the colony mirrors history's treatment of the colony itself. From early on, people recognized the importance of these documents. In 1801 a committee headed by none other than Aaron Burr declared that “measures ought to be taken to procure a translation,” but none were. In the 1820s a half-blind Dutchman with a shaky command of English came up with a massively flawed longhand translation—which then burned up in a 1911 fire that destroyed the state library. In the early twentieth century a highly skilled translator undertook to translate the whole corpus only to see two years' worth of labor burn up in the same fire. He suffered a nervous breakdown and eventually abandoned the task.

Many of the more significant political documents of the colony were translated in the nineteenth century. These became part of the historical record, but without the rest—the letters and journals and court cases about marital strife, business failures, cutlass fights, traders loading sloops with tobacco and furs, neighbors stealing each others' pigs—in short, without the stuff from which social history is written, this veneer of political documentation only reinforced the image of the colony as wobbly and inconsequential. Dr. Gehring's work corrects that image, and changes the picture of American beginnings. Thanks to his work, historians are now realizing that, by the last two decades of its existence, the Dutch colony centered on Manhattan had become a vibrant, viable society—so much so that when the English took over Manhattan they kept its unusually free-form structures, ensuring that the features of the earlier settlement would live on.

The idea of a Dutch contribution to American history seems novel at first, but that is because early American history was written by Englishmen, who, throughout the seventeenth century, were locked in mortal combat with the Dutch. Looked at another way, however, the connection makes perfectly good sense. It has long been recognized that the Dutch Republic in the 1600s was the most progressive and culturally diverse society in Europe. As Bertrand Russell once wrote, regarding its impact on intellectual history, “It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of Holland in the seventeenth century, as the one country where there was freedom of speculation.” The Netherlands of this time was the melting pot of Europe. The Dutch Republic's policy of tolerance made it a haven for everyone from Descartes and John Locke to exiled English royalty to peasants from across Europe. When this society founded a colony based on Manhattan Island, that colony had the same features of tolerance, openness, and free trade that existed in the home country. Those features helped make New York unique, and, in time, influenced America in some elemental ways. How that happened is what this book is about.

I

CAME TO

this subject more or less by walking into it. I was living in the East Village of Manhattan, a neighborhood that has long been known as an artistic and countercultural center, a place famous for its nightlife and ethnic restaurants. But three hundred and fifty years earlier it was an important part of the unkempt Atlantic Rim port of New Amsterdam. I often took my young daughter around the corner from our apartment building to the church of St. Mark's-in-the-Bowery, where she would run around under the sycamores in the churchyard and I would study the faded faces of the tombstones of some of the city's earliest families. The most notable tomb in the yard—actually it is built into the side of the church—is that of Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch colony's most famous resident. In the mid-seventeenth century this area was forest and meadow being cleared and planted as Bouwerie (or farm) Number One: the largest homestead on the island, and the one Stuyvesant claimed for himself. St. Mark's is built near the site of his family chapel, in which he was buried. Throughout the nineteenth century New Yorkers insisted that the church was haunted by the old man's ghost—that at night you could hear the echoed clopping of his wooden leg as he paced its aisles, eternally ill at ease from having to relinquish his settlement to the English. I never heard the clopping, but over time I began to wonder, not so much about Stuyvesant, who seemed too forbidding for such a verb, but about the original settlement. I wanted to know the island that those first Europeans found.