The Intern Blues (31 page)

Authors: Robert Marion

Okay, so I did all that, and then I got to spend the next six hours writing progress notes. I love writing progress notes! You have to write a note on every patient every day or else the administrator on duty swoops down at about midnight and puts an evil spell on you. And these notes aren't just “Patient still alive. Plan: Make sure he stays alive until tomorrow morning.” These notes go on and on, listing problem after problem. Each one can take an hour.

It wouldn't even be so bad if all I had to do was the scut and the notes, but that's all broken up by the endless rounding. First the attending showed up at about eleven so that he could view the patients close up for about an hour. He also has to fill his daily quota of yelling at the house officers. Then in the evening, there were rounds with the senior resident, who managed to come up with a whole new list of scut for me to take care of during the night. So I got to draw some more blood, have more fights with the lab technicians who have perfected the art of denying having received blood samples you handed them not an hour before, and write more long notes in the charts documenting what the results of those fights with the lab technicians have been.

And even all that would have been okay if it hadn't have been for the fact that the DR

[delivery room]

kept calling us to come down to deliveries. That's the real ulcerogenic part of this job. The rest is just irritating, but the DR is downright frightening. At any moment, without so much as a minute's warning, you could be called down there and find yourself face to face with a brand-new four-hundred-gram wonder whose only goal in life is to make your next two or three weeks completely unbearable. Also, there are all these little emergencies that come up in the unit, like kids deteriorating or spiking fevers, stuff like that. It's all such fun!

Last night, I actually got myself in a position to go to sleep at about three o'clock. I was in the on-call room, in my winter coat, getting ready to lie down on the cot. The on-call room is an interesting place. They recently rebuilt the entire ICU and they made us this very nice place to sleep. The only problem is, they forgot to put any heat in there. The average temperature is about forty to forty-five degrees. Sleeping in there is like camping out in Alaska.

Anyway, I was on the cot, getting ready to lay down. I was lowering my head toward the pillow and just as my hair made contact with the pillowcase, my beeper went off, calling me to the DR stat. I went running down there to find it was an uncomplicated problem, a little meconium-stained amniotic fluid. The baby was out by the time we got there and he was fine, just fine. There was nothing we needed to do. So I went back to the unit, got back into the on-call room, put my coat back on, and actually got about an hour of sleep. At five o'clock, I got another stat page. We went running down to the DR, and what did we find? An obstetric resident with her arm, up to the elbow, thrust inside a woman's vagina. What a romantic sight!

It turned out, this woman had wandered in off the street with a prolapsed cord.

[The umbilical cord had come through the cervix and was lying in the vagina. The danger of this is that if the cervix should close up again, blood would stop flowing through the umbilical cord and the fetus would suffer from lack of oxygen, causing either death or severe brain damage.]

The resident was trying to push it back up into the uterus while two other people were preparing to do an emergency C-section. The whole thing took about an hour, and when the baby came out, he was just fine! By that point it was eight o'clock in the morning and time for the day crew to show up. I finished with the work on that patient, started drawing the morning bloods, and then started rounds with the rest of the team.

We went on work rounds and then we had attending rounds. I tried to write my notes during all this because I had clinic this afternoon and I didn't want to have to come back to the unit again after clinic was over. So I got to clinic at Mount Scopus at about two and I got home a little while ago, at about six. A typical thirty-four-hour day; at least I got one whole hour of sleep!

I've had some really terrific experiences in the unit over the past week. Really terrific! I've got these two kids who are essentially brain stem preparations. One weighed 525 grams at birth and from the very beginning had virtually no chance of surviving. So what do we do? We use everything we have to keep him alive. And all that comes out of it is a great deal of work for me and the other interns. The other kid was good-sized at birth, a thirty-three- or thirty-four-weeker, but the mother had an abruption

[abruptio placentae: a condition in which the placenta tears itself off the wall of the uterus, leading to a great deal of bleeding and a severe deficiency of blood in the fetus]

and the kid was severely asphyxiated, with Apgars of 0, 0, 3, and 3. Not what you'd call very good. Where I come from, we have a name for children like this: stillborn. So this kid is basically brain dead but we're keeping the body alive to have something to keep us busy. As if I already didn't have enough to keep me busy!

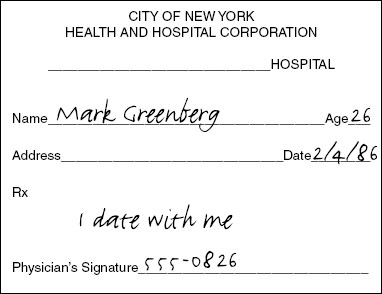

This rotation continues to have only one redeeming feature, that being the nurses. These nurses are fantastic. They're young, real attractive, and real good at their job. Last week one of the night nurses handed me a prescription form. It looked like this:

I've been carrying it around ever since. I had lunch with her last week. She seems nice. I don't want to jeopardize my relationship with Carole; Lord knows it's already suffered enough! So I don't think I'll actually take this any farther. But it sure was nice to get that note. It made me feel . . . it made me feel almost as if I were a human.

Tuesday, February 25, 1986

I haven't recorded anything in a couple of weeks. I look upon these tape recordings as kind of a funny running monologue, but I haven't felt very funny over the past two weeks. Working in this unit has been terrible, just terrible, much worse than I ever imagined. We've had a lot of deaths and, even worse, we've had a lot of survivors, babies who should never have been allowed to live. I don't want to think back on what's happened, I just want to look ahead. In just a couple of days I'll be done with the NICU, and then I've got a month in OPD at Mount Scopus, two weeks of vacation, and two more weeks of OPD after that.

Every month so far there have been a lot of bad memories, but there have also been some good ones, funny stories. I'll carry with me probably forever. This month there have only been bad memories and worse memories. Moreno and his steadily increasing head circumference; the wasted, dying preemies hanging on much longer than they should be allowed to because of all the machines we have to use on them; the bigger kids with PFC

[persistence of the fetal circulation]

; the brain-dead baby with the abruption; these were terrible, terrible things. I've been finding that I just can't defend myself against them. It's been just brutal.

I don't want to make this sound too sappy, but I knew I was in trouble when I cried in the hospital last week. Iris, the other intern, has been crying just about every day, but last Thursday I had been up the whole night before with this PFC'er who had done really poorly, and when he finally died, I just couldn't take it anymore. I went into the bathroom, locked the door, and just cried my eyes out. I'm really starting to fall apart. That was the first time I'd cried all year. I know most of the other interns have cried, but I kind of prided myself on the fact that I could control myself. Not this month.

Maybe sometime in the future I'll be able to come back to this and fill in some of the blank spaces I've left, but I can't do that right now. I need a nice vacation. I think I'll take my vacation in the West Bronx emergency room over the next four weeks.

I'm going to sleep. Maybe when I wake up, things'll start being funny again.

Â

Mark Greenberg and Andy Baron worked in ICUs during February, and both had experiences caring for patients who were being kept alive thanks to technological advances that had been developed over the past few years. It's always been true that technology has run way ahead of ethics in medicine. With every advance that's been made, be it the development of antibiotics, the iron lung, present-day respirators, chemotherapy and radiotherapy for cancers, or the ability to transplant organs, physicians have been able to take discoveries made in the laboratory and apply them to humans. The immediate result of these advances has been that patients who the week before would surely have died have been given the opportunity to survive, at least for some period of time. But we've often learned that survival may not always be the best outcome for the patient or for society. The question of whether these fruits of medical technology should be utilized has to be addressed. In many cases, answering this question can be more difficult than developing the technology in the first place.

In no place is this truer than the neonatal intensive-care unit. Although there has always been interest in the very premature baby, until the 1960s these infants were considered little more than curiosities. Rather than being cared for in specially designed intensive-care units where all their life functions were meticulously monitored, these babies used to be warehoused in circuses and freak shows, and exhibited to the public for a price. If they lived for very long, it created more interest. If they died, usually because of respiratory failure, it meant only that they needed to be replaced.

Unlike most other medical specialties, which gradually evolved into existence, neonatology had a sharply demarcated beginning, largely the result of a specific event. In August 1963, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, the premature son of President John and Jacqueline Kennedy, died of respiratory distress syndrome at Boston Children's Hospital. For a few days, an intense media spotlight was shone on the special problem of babies who were born too soon. Although, sadly, this event ended with the death of the infant, it resulted in millions of dollars of national grant funding being devoted to research into the special problems of the premature. And therefore the death of Patrick Bouvier Kennedy led to neonatology as we know it today.

The major advances in the field occurred early. By the mid-1970s, using respirators, intravenous medications and fluids, specially developed dietary formulas, and very aggressive care, it became technically possible to keep alive infants who were born as much as fourteen weeks prematurely and who weighed as little as twenty-eight ounces. Some of these infants did well; they've gone on to lead relatively normal lives. Most of the other survivers, though, have been left with significant physical and developmental problems: Some developed cerebral palsy and required orthopedic intervention and braces to help them walk but were otherwise spared; others were found to have suffered extensive brain damage and, in addition to cerebral palsy, were left with mental retardation and seizures; still others were so extensively damaged by the consequences of their prematurity that they wound up leading a vegetative existence, many residing in institutional settings. And so the question was raised, “Although technically possible, is any of this justified?” Neonatologists and medical ethicists have been struggling to answer this question ever since.

Neonates with problems can be divided into three groups. A first group includes those who have an excellent prognosis right from the beginning. This group includes the “garden variety” preemie who weighs two pounds or more and who is born without any problem other than prematurity. Most everyone in the field of neonatology would agree that everything possible should be done to support these infants.

A second group is made up of those infants who are born with such severe defects that survival is not possible no matter what is done for them. Included in this group are babies with anencephaly, a condition in which the skull and brain fail to develop; all of these infants are either stillborn or die within the first days of life. Also included in this group are babies born before twenty-four weeks of pregnancy. Most but not all neonatologists feel that these infants should be made as comfortable as possible and be allowed to die without intervention.

The third group of infants with problems is the most difficult ethically. It is made up of those children who fit between these two extremes: babies born weighing less than two pounds but above the twenty-fourth-week-of-pregnancy cutoff; and infants with major birth defects that are not necessarily lethal. The medical community is divided about what to do with these babies. Many neonatologists would do everything possible to offer these infants the opportunity to survive, knowing that possibly for every surviver who turns out to be normal, there'll be an infant or two who will wind up significantly damaged. Others would provide limited care, reasoning that the “strong” will survive and the “weak” will die off (the problem with this reasoning is that some in the former group who would have led a normal existence had aggressive care been provided will wind up damaged as a result of this method). Finally, some would argue that nothing should be done for this middle group and that nature should be allowed to take its course; physicians who think this way are clearly in the minority.

In neonatology, there's a tendency to lose sight of the end point. Sometimes a neonatologist who understands that he or she has the tools to keep any newborn alive for as long as he or she wants, may decide to flex his or her technological muscles and play God, keeping alive children who should be allowed to die. Neonatologists might argue that these exercises are good in the long run: By learning about keeping these children alive even for a brief period today, it might someday be possible for some to survive. And there might be some truth to this; after all, the argument that nothing should be done could have been made twenty years ago concerning babies who weighed twice what the babies who survive today weigh. But the question is, What price is being paid for this?

During his month in the NICU, Mark was kept awake night after night caring for babies some of whom he considered brain dead, one of whom weighed only a little over seventeen ounces. Discouraged because of all the inevitable deaths, he asked, “What possible good am I doing here?” It didn't seem as if many of the babies were benefiting from the intensive care. The parents, who were seeing everything done for their infants, were being given false hope; they reasoned, “If they're doing so much, they must believe that my baby has a chance to survive.” This winds up making coping much more difficult for the parents when the baby ultimately does die.

Taking care of patients who have no chance of surviving is extremely frustrating and anxiety-provoking. You're asked to do things that don't make sense to you; you're called upon to counsel parents without having the picture clear in your own mind. But this state of mind is not limited to working in the NICU. These problems also occur in other intensive-care units.

Physicians working in ICUs that care for older patients must deal with many of the same issues as the neonatologist, but the situations are often radically different. Patients in the pediatric or adult intensive-care units are not neonates; they come into the unit with a life history. They have relatives and friends who know them and love them, not just for what they might be in the future but also for what they've been in the past. They have personalities and desires, and often specific requests about what should and should not be done. The intensivist must often decide whether to honor these requests, or the requests made by the patient's loved ones, or to do whatever he or she thinks is in the patient's best interests. And that can be very difficult.

During his month in the pediatric intensive-care unit, Andy became involved with three patients for whom “do not resuscitate” orders were ultimately written. Actual orders stating that a specific patient should not be resuscitated in the event of a cardiac or respiratory arrest are new at Mount Scopus Hospital. Prior to the time that the present interns began their year, plans for patients who had no chance of survival were formulated through conversations among the physicians, the family, and, if possible, the patient. If it was agreed by all parties that resuscitation should not be attempted, the word would be passed to all members of the care team. The concept of a patient being a “no code” developed; then the concept of a limited or “slow code” (the situation in which cardiac arrest leads to limited efforts at resuscitation) evolved. Verbal “no codes” were troublesome; to many members of the care team, it seemed like a sham. Notes and orders were being written in the patient's chart that did not truly reflect the thoughts of the care providers or the wishes of the patient and his or her family. But DNR orders could not be written; they raised legal and ethical questions that had not yet been answered.

The use of written, formalized DNR orders arose through the efforts of a committee composed of the hospital's lawyers, ethicists, and physicians. Now the true plan for a specific patient can be spelled out in the chart without fear of legal or ethical retribution. The actual order must be written by the patient's attending physician and must be reordered every week. Once a DNR order has been written, it leads to conflicts of another sort: Now that we've stated that the patient is expected to die, what should and what should not be done for that patient?

Here's an example that'll help explain this conflict: A patient who is DNR develops a fever. Normally, hospitalized patients who develop fever are managed very aggressively; a “sepsis workup” consisting of blood and urine and sometimes spinal fluid cultures is done, and antibiotics are immediately begun. Failing to treat a patient with fever may lead to overwhelming infection and ultimately to death. But what should be done if the patient is DNR? Should antibiotics be started on such a patient, or should infection and its consequences be “encouraged”? If antibiotics are going to be withheld, should cultures be obtained? These questions must be considered in every case. Often, under the reasoning that to treat an infection would be to prolong life artificially, antibiotics will not be given and cultures will not be obtained.

But using this reasoning, one could argue that feeding the patient would also lead to artificial prolongation of life. Therefore, should DNR patients receive the nutrition they require for life to continue, or should they be allowed to starve to death? Most physicians would agree that the withholding of nutrition should not occur. Implicit in DNR is that the patient should not be allowed to suffer. Starvation is a painful and drawn-out way to die. Therefore, most intensivists would make sure all patients were receiving an appropriate number of calories to sustain life.

These are only some of the issues Andy and Mark agonized over during their month in the ICU. And they are not alone. The conflicts that arise for young physicians at the edge between life and death are universal. And they lead to a great deal of mental and emotional stress and anxiety.