The Inquisitor's Apprentice (29 page)

Read The Inquisitor's Apprentice Online

Authors: Chris Moriarty

"So what do we do now?" Lily asked.

Sacha read through the summoning spell one last time. There were a lot of words in it that he didn't understand. In fact, struggling through the archaic Hebrew had reminded him uncomfortably of preparing for his

bar mitzvah.

He was starting to think that he might turn out to be just as bad at summoning dybbuks as he'd been at memorizing Torah lines.

To be honest, he was hoping he would be.

"First we need to draw a circle on the floor," he told the two girls. "Then we need a bedsheet."

"Cripes," Lily complained. "You could have

told

me you needed a bedsheet."

"And chalk," he added. "Did anyone bring chalk?"

"No. Did you?"

"If I'd brought it, would I be asking you?"

"Just because you're scared," Lily observed in her prissiest voice, "is no reason to be rude."

"Shhh!" Rosie hissed. "Someone's coming!"

They all dove to the floor and lay there while footfalls sounded on the street outside and dim lights swept across the room. As the footsteps faded off down the street, Rosie crept to the shopfront window and gave the all clear.

Sacha sat up to find Lily staring at him. The false alarm seemed to have shaken her. She was obviously having second thoughts.

"Sacha?" she asked hesitantly. "Don't you think maybe we really should ask Inquisitor Wolf for help instead of trying to do this ourselves?"

Of course I do, he wanted to tell her, but that would mean admitting why he couldn't ask Wolf for help. So instead he just shrugged.

"He could help you," Lily said stubbornly. "I thinkâI think he might even be a Mage."

"That's ridiculous," Sacha snapped.

Lily gave him a decidedly odd look. "Are you sure? My mother saidâ"

"And what does your mother know about magic anyway?" he asked bitterly, wishing his family was as all-American as the Astrals instead of littered with Kabbalists and miracle workers. "But you people are always full of advice, aren't you? It's easy to tell other people what to do when you don't have to live in the real world and you've never wanted a thing in your life that someone didn't hand you on a platter. Just like they handed you this job, when we all know that the only thing you're really going to do with your life is turn into a useless socialite like your

mother!

"

"I'm nothing like my mother!" Lily shouted. Then she stopped and bit her lip as if to keep it from trembling. "Never mind. Forget I said anything. It was a stupid idea anyway."

"Ugh!" Rosie said into the angry silence. "This place is filthy!"

She was right, Sacha realized. Mo Lehrer was a perfectly good

shammes,

of course. But he was, after all, a man. And as Sacha's mother was fond of saying, your average man's idea of housecleaning stopped about where your average woman's notion of slatternly filth started. Mrs. Kessler mopped her floors daily in order to battle the black soot that rose from a million coal fires to blanket every surface in the city. Mo, on the other hand, just swept up occasionally. And it showed.

"Well, at least we won't be needing chalk," Sacha pointed out. "We can draw in the dust. We ought to post a lookout, though. Lily, why don't you stay by the window and watch the street."

"Fine," Lily muttered in a voice that made it clear she was still nursing bruised feelings.

Just like a girl, Sacha told himself. Well, maybe he had been kind of mean. But he could always make it up to her later. And even a girl couldn't expect him to drop everything and apologize now.

"So what do we do next?" Rosie asked. "Shouldn't you put on your phyâphyâyou know, those string things."

"I don't know," Sacha said.

"Well," Rosie said with elaborate care, "what do you

think?

"

"I think my grandfather would have a stroke if he knew about this."

"Yeah, butâ"

"All right, all right! Enough already, I'm doing it."

Sacha dutifully donned phylacteries and prayer shawl. Suddenly he was dead certain that this was the worst thing he'd ever done in his life. He tried to make himself feel better by thinking about the story of the rabbi who'd said a Yom Kippur service in hell, setting all the demons free to go to heaven and condemning himself to eternal damnation in order to save them. He tried to imagine that he was doing something noble like that, that he was somehow sacrificing his own soul in order to save ... well ... someone. Part of him knew it was all hooey. But he was in too deep to back out.

So Sacha drew in the sooty dust. For a bedsheet they used an old furniture cloth Mo had nailed up in the doorway that led into the back room. It took a few curses and torn fingers to pry the rusty tacks loose from the doorframe, but the cloth would do.

"After all," Rosie pointed out, "nothing says it has to be a

clean

bedsheet."

Maybe it was Sacha's bad Hebrew, but Grandpa Kessler's books didn't seem to explain what to do with the bedsheet. It was supposed to go in the circle, that much Sacha got. So first they tried just laying the sheet on the floor in the middle of the circle.

Rosie tucked the corners in so that they weren't smudging any part of the circleâthis, at least, the practical Kabbalah books had been quite clear about. Then she backed up and looked at it quizzically.

"What's that supposed to do?" Lily asked from the window.

"The dybbuk's supposed to appear behind it."

"But ... there

is

no behind it."

"Maybe we should have left the sheet hanging up in the doorway and done the circle over there," Rosie suggested. But none of them liked the idea of having to lift the sheet knowing that the dybbuk could be anywhere in the cluttered back room watching and waiting for them.

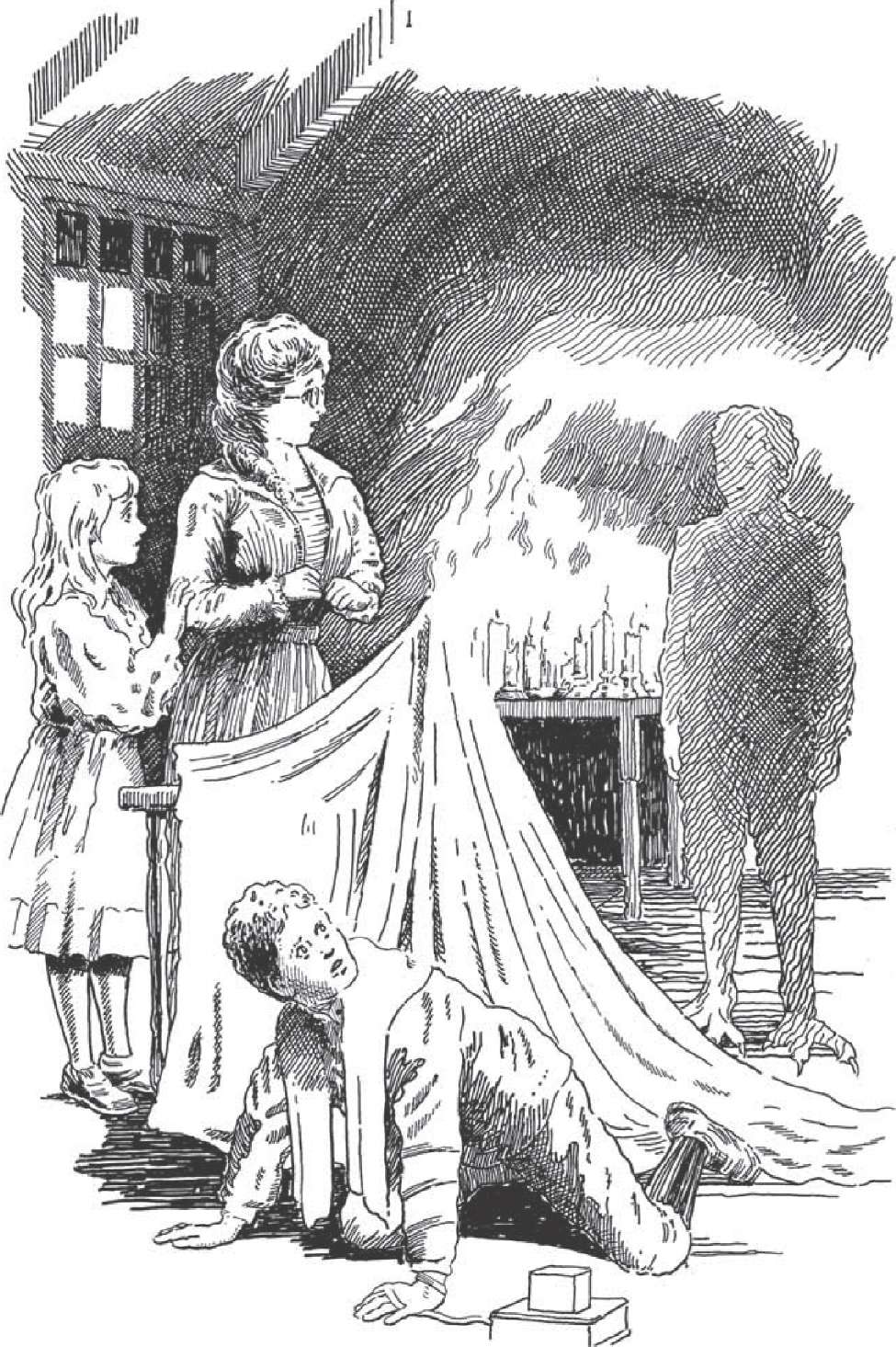

In the end they compromised by dragging a couple of chairs into the circle and arranging the sheet over them so it formed a sort of tent. It reminded Sacha of the secret forts he and his sister used to make under the furniture on rainy days. There was still something creepy about that dark cave under the sheet, but at least this way the dybbuk wouldn't have a whole room to run around in.

Sacha neatened up the circle, which had been smudged alarmingly by their rearranging of the sheet. Then he took a final look at the spellbooks just for good measure.

"Oh, no! This book says you have to

feed

the dybbuk." He leafed frantically through the other books. "None of the other ones says anything about food! How was I supposed to know?"

"Not to worry," Rosie said, pulling a newspaper-wrapped package out of her coat.

"What's that?" Sacha asked.

"A cannoli."

"How do you know dybbuks like Italian food?"

"I don't want to knock anyone's national cuisine," Rosie said, "but trust me: even a dybbuk can't prefer dried-up noodle kugel to a cannoli from Ferrara's!"

Over by the door, Lily looked almost as doubtful as Sacha felt. But it turned out that she had a more practical concern than the dybbuk's taste in food. "We don't even know if dybbuks have fingers. Shouldn't you unwrap it?"

"Good point." Rosie undid the strings and paper to reveal what just might have been the most perfect piece of pastry Sacha had ever seen in his life.

"

Where

did you find

that?

" Lily asked in tones of religious awe.

"And what is it again?" Sacha asked.

Rosie gave them the kind of look New Yorkers usually reserved for tourists. "You two need to get out more."

When the perfect cannoli had disappeared under the sheet, Lily sighed deeply and said, "Okay. What do we do now?"

"I'm supposed to make a secret sign and say, 'Spirit of the Invisible World, prisoner of the realm of chaos, I, Sacha, son of so-and-so, summon you. Come. Eat. Eat and be satisfied.'"

Sacha said the words.

Nothing happened.

Lily coughed, and Sacha jumped halfway out of his skin at the sound.

"Sorry. Uh ... I think you forgot the secret sign."

"Oh. Right."

But when he did the words and made the sign at the same time, nothing happened again.

They waited a minute.

Still nothing.

"Try it with your left hand," Rosie suggested.

Sacha tried it with his left hand.

More nothing.

"Or backwards, maybe?" Lily hazarded. "Do you think you could do it backwards?"

"I'm going home!" Sacha threw up his hands in disgust and walked away from the circle. "This is the dumbest thing I've ever done. I've already ruined a perfectly good pair of pants, and I'm not going to hang around and get arrested by the police on top of it. You two can do whatever you want. I'm leavâ"

Then he heard one of the chairs fall over.

He was facing Lily when it happened, and he knew right then that he would remember the look of terror on her face if he lived to be a hundred and twenty.

"

I'm so sorry,

" she whispered. "

I would never have let you do this if I'd really thoughtâ

"

For one crazy moment, Sacha had the idea that he could just run past her and out the door onto the street and get away. But he knew better. There was no running away now. There was nowhere to run to.

The dybbuk was wearing Sacha's second-best pants and shirt, just as he'd known it would be. The shirt was so clean that Sacha had a bizarre vision of the dybbuk conscientiously washing it at the back lot water pump long after the lights had gone out and everyone in the tenements had drifted off to sleep. It gave him the shudders. However awful it was to think of the dybbuk hurting and killing, it was even worse to think of it trying to be an ordinary boy.

"What do we

do?

" Lily whispered.

Sacha looked at Rosie, who just spread her hands helplessly. "Didn't the book say how to get rid of it?"

"No. Or if it did, I didn't read that far."

"

Sacha,

" Lily whispered urgently behind him.

He ignored her.

"

Sacha! The circle!

"

Sacha looked downâand saw that somewhere in the process of summoning the dybbuk, he had stepped on the circle. It was barely a smudge, really. A scuff mark at most. But it was enough.

The dybbuk felt its way around the edge of the circle

until it found the smudged spot. Then it wafted out through the gap like cigarette smoke wafting through a keyhole.

There was something about the way it moved that made Sacha queasy. He looked down and felt his stomach heave; the old wives' tales were true, he realized. Or at least partly true. Because even though the dybbuk's feet looked normal enough, the footprints they left behind were very far from normal. It looked like some monstrous bird had scratched its way across the dusty floor of the

shul.

The dybbuk oozed toward him on its horrible bird feetâand then it oozed past him and over to Lily, who was still frozen by the window in horror.

It raised one filmy hand and touched Lily on the chest, right above her heart. It started to get that sinuous, flowing, cigarette-smoke look again. But this time it wasn't flowing out of the circle. This time it was pulling something out of Lily.

The sight was so strange and awful that for a moment Sacha just stared. Then a sort of electric shock went through him. The dybbuk was sucking the life out of herâand he was standing there watching it happen like some tourist gawking at the Flatiron Building!

He flung himself at the dybbuk. It felt like tearing at a cloud, but finally he grabbed hold of his second-best shirt and dragged the creature back across the room by its collar.

They careened into the circle, and Sacha wrenched one arm free in a desperate motion and somehow managed to redraw it around them.

He had no idea how long the struggle lasted. Later it seemed that only a few seconds had passed. But while he was grappling with the dybbuk, he felt as if years and decades of his life were sloughing off him.

At first he thought he'd never be able to hold the dybbuk. Every time he tried to lay hands on it, it wafted away, leaving nothing but empty air behind. But as they struggled, the dybbuk took on weight and substance. Soon Sacha wasn't chasing smoke. Now it was more like trying to hold water in his bare hands. He still couldn't get a solid grip, but he could feel it slipping through his fingers, leaving them as numb and painful as if he'd been clutching at ice.

Outside the circle, Lily and Rosie were screaming at him. He could tell they were trying to warn him about something, but their words couldn't seem to reach him.

Meanwhile the dybbuk grew more real and solid with every passing moment.

Its breath smelled like the worst tenement air shaft in the world. It reeked of rancid oil and dead rats and broken razors and deathbed linens and all the other revolting things that people want to get rid of so badly they can't even wait for the Rag and Bone Man to come round for them.

But there was worse, far worse, than the dybbuk's breath. Sacha felt its thoughts and feelings as well. He felt its ravenous hunger for life and warmth and love and family. He felt its furyâso strong that it had become a strange, twisted sort of self-hatredâat the thief who had stolen its life from it.