The Incredible Human Journey (52 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

Reasonable assumptions are all well and good, but ultimately all this musing about a North American coastal route is, at the

moment, conjecture. The genetics may suggest a coastal route, and the conditions may have been suitable (judging from pollen,

bears and kelp) for a coastal expansion from 17,000 years ago, but there is no hard evidence for people living along Canadian

shores that long ago. The Palaeolithic archaeologists of North America suffer the same problem that plagues those trying to trace ancient migrations just about

everywhere else in the world: glaciation has scoured continents and destroyed a wealth of archaeological evidence in its path,

and the rising sea levels produced when the ice melted have concealed the Pleistocene coasts. Presumably many of the traces

of the first colonisers could be lost beneath the waves. Most of Beringia is now under water, like a Stone Age Atlantis, and the coastline of Alaska and Canada is much higher and

further inland than it would have been at the end of the Pleistocene.

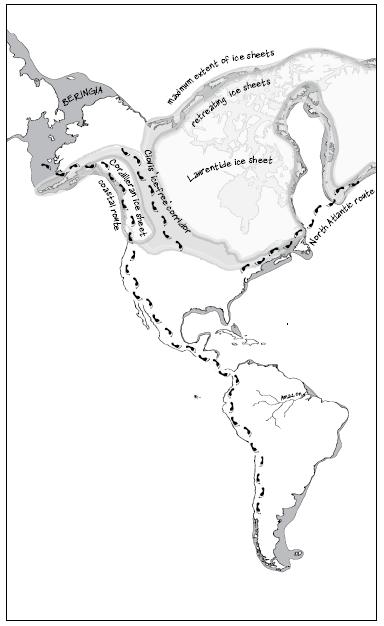

The map shows the ice sheets of North America during the Last Glacial Maximum,

stretching from coast to coast, and the retreating ice sheets. The north-west coast became

deglaciated about 16,000 years ago, freeing up a potential coastal route into the

Americas; the interior ice-free corridor opened 14,000 to 13,500 years ago; the map

also shows Bruce Bradley’s suggestion of a North Atlantic route.

There are some intrepid archaeologists who have explored the submerged Pleistocene coasts of north-west Canada, using sonar

to map the sea floor. They found a drowned landscape of ancient rivers, lakes and beaches,

6

a landscape that would have been available for humans to inhabit one to two thousand years earlier than the opening of the

inland ice-free corridor. This ancient coast was later covered up by a relatively rapid rise in sea level, and this makes

the archaeologists very optimistic that any archaeological sites would have been quickly buried under the seabed, and are

therefore likely to have been well preserved. Gradual increases in sea level cause much more erosion as they occur,

7

and in fact one piece of archaeology

has

emerged from under the waves: a barnacle-encrusted stone tool was recovered from an ancient river mouth now 53m underwater.

For the first actual, datable evidence of people on the North American coast, I would have to travel south: to California.

Finding Arlington Woman: Santa Rosa Island, California

Just off the coast of Southern California, across the Santa Barbara Channel, lie the Channel Islands. These islands are rich

in wildlife and have been home to humans for thousands of years. Historically, the archipelago was settled by Chumash and

Tongva Indians, who used purple olivella shells as currency. Spanish explorers, missionaries and ranchers arrived on the islands

in the sixteenth century, and nineteenth-century fur traders hunted the native sea otters and seals nearly to extinction.

Now the islands and their diverse wildlife are protected, as part of a National Park.

I flew to Santa Rosa in a six-seater prop plane, late in the day. We took off from Camarillo airstrip and were quickly over

the Santa Barbara Channel, heading west. I could just make out the Channel Islands on the horizon. We flew over Anacapa Island,

then over the larger island of Santa Cruz, just to the north of its Diablo Peak. The islands were rocky and rugged, with very little sign of human habitation.

We started descending over the sea, then came into land on a short, dusty airstrip just set back from the shore at Bechers

Bay. I was met by rancher Sam Spaulding in his Hilux and we set off on a track that rose steeply into the mountainous interior

of the island. Although park wardens and scientists were frequent visitors, there were no permanent residents on Santa Rosa

Island. I was staying at the National Park lodges, high up in the hills. I arrived there just as the sun was setting, and

I met John Johnson of the Santa Rosa Museum of Natural History, who had come out to the island to be my guide for a trip to

Arlington Springs on the other side of the island.

The following morning we set off early and drove for two hours along rough tracks to the gully known as Arlington Springs.

The landscape we passed through was magnificent, sculpted by water. Over the millennia, streams and rivers have gouged deep

gullies and canyons in the sandstone, naturally exposing ancient sediments. And in those sediments are fossils of the various

long gone inhabitants of Santa Rosa.

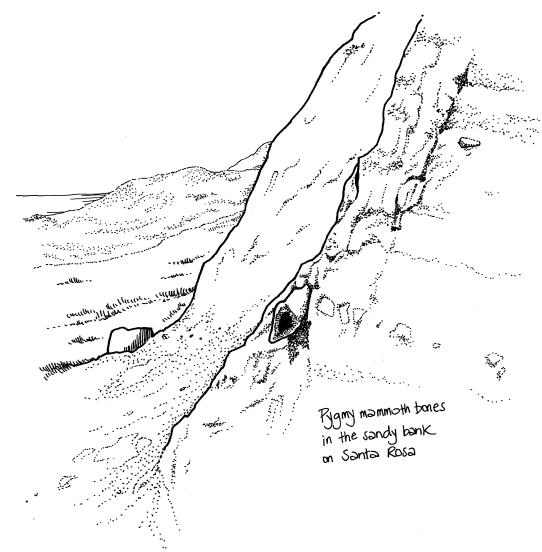

John and I scrambled down the steep banks of the gully to the stream, which meandered its way towards the coast. On the way

there were waterfalls and plunge pools that we had to edge around to follow the water down to the sea. In the walls of the

gully I could easily make out the layers and layers of sediment that had built up over millennia to then be cut back by the

stream. In deep layers, there were fossilised shells: great, clam-like things and ridged bivalves. These were very ancient,

from a time when this sediment had been on the bottom of the sea. As we walked downstream, we came across younger sediments,

and John pointed out fossil bones sticking out of a reddish bank: a line of crumbly vertebrae and some long bones. Pygmy mammoth

bones, no less.

In 1959, an archaeologist named Phil Orr had been drawn to Santa Rosa Island by its rich Pleistocene fossils. He was trying

to create a new track down the side of Arlington Springs gully with a grader, to reach an excavation near the beach. His vehicle

became stuck in the gully, and when he got out and looked around he spotted two long bones poking out of the side of the gully,

11m below the top of it. The bones were in the same – Pleistocene – layer as the mammoth bones he was more familiar with.

But these weren’t mammoth bones. Orr called on the advice of other experts who confirmed what he had suspected: the bones

were human. It looked as if he had found the first evidence of ancient humans on the island. The bones were two femora (thigh

bones). There was no sign of the rest of the skeleton: the femora were ‘disarticulated’. They appeared to have been washed

into the gully and then covered up by later layers of sediments. Orr removed the bones in a block of earth, and, back at the

lab, removed fragments to send for radiocarbon dating. In 1960, he published the results: the femora were 10,000 years old.

1

Orr thought the bones to be robust and most likely male, and the find became known as ‘Arlington Man’.

In 1987, John Johnson and his colleague Don Morris had found Orr’s plaster block containing the Arlington Springs bones in

the basement of the Santa Rosa Museum, and decided to subject the bones to some modern analyses, including DNA tests and the

more reliable AMS radiocarbon dating. Anthropologist Philip Walker looked at the bones and decided that they were most likely

to be from a woman: the rough line down the back of the femur where thigh muscles attach was very faint, not robust as it

often is in male skeletons, and the slender diameter of the bones also suggested that they were female.

1

John showed me reconstructions of the femora, and they were indeed very lightly built. Radiocarbon dating of the human bone

itself, and on an associated extinct mouse deer mandible that was buried close by, yielded a date of around 12,900 years ago

2

– meaning the skeletal remains of ‘Arlington Woman’ were indeed among the oldest known in North America.

Although these human remains date to several thousand years after the coastal corridor is thought to have become accessible,

they do prove something about the earliest Californians: they must have used boats. At the height of the last Ice Age, the

three islands of San Miguel, Santa Cruz and Santa Rosa were joined together, as a single super-island which has been called

Santarosae, but it was always separate from the mainland.

3

,

4

In the 1990s, John Johnson was part of a team of archaeologists and palaeontologists who, following up Phil Orr’s work, undertook

a comprehensive survey of the island, looking for Pleistocene fauna in particular. They didn’t find any more human bones,

but they did discover plenty of mammoth fossils, all around the coast of Santa Rosa, in alluvial sediments cut through by

water action – just like the bank with the mammoth fossils that John had shown me. They also uncovered an almost complete

skeleton of a pygmy mammoth, and when they radiocarbon dated the bones they found them to be almost exactly the same age as

Arlington Woman. In fact, there seemed to be an overlap of around two hundred years. This was an important result. Mammoths

had been on the island for around 47,000 years, and now the archaeologists could be sure that there was a period when pygmy

mammoths and humans were contemporary on Santa Rosa, as Orr had suspected. Orr also believed that humans had played a key

role in the extinction of these diminutive mammoths. It is difficult to support such a theory on the basis of the Santa Rosa

material alone, founded on dates from ‘one mammoth, one human, on one island’,

3

and there is no ‘smoking spear’ to prove human predation on mammoths. Nevertheless, it still seems a remarkable coincidence

that, within two hundred years of humans arriving on Santa Rosa, the mammoths had disappeared. In many ways, the evidence

from this island is tantalising but frustrating. In spite of some continued archaeological investigations on the island, the

only evidence of humans there in the Pleistocene is those thigh bones. Nothing else: no other bones, no evidence of any occupation

sites. What was that woman doing on Santa Rosa? If she was part of a band of hunter-gatherers living there, no other trace of these people has appeared – yet. Humans may have killed off the miniature mammoths on the island, but for more evidence of human involvement in the extinction

of Pleistocene fauna, and of the beasts themselves, I would need to return to the mainland.

John and I had wandered down Arlington Springs gully all the way to the seashore, and we sat down on a sand dune to talk about

his other research, in genetics and phylogeography. John had become fascinated by the language families of the Californian

Native Americans, including the Chumash.

Languages can certainly suggest population origins and movements, but they are also transferable – like other aspects of culture

– and so it’s very difficult, even impossible, to reconstruct the deep evolutionary history of people around the world on

the basis of variation in language. For John, the suggestions emerging from the linguistic studies warranted further investigation, and mtDNA analysis seemed

to be the perfect tool. But it was a telephone call from a friend that had really set John off on the trail of tracing ancient migrations.

‘A few years ago, a friend of mine called me up and told me there was this tooth from an ancient jaw from southern Alaska,

that had DNA that was a very rare type.’

I asked him how old the tooth was.

‘It was 10,300 years old – the oldest skeletal remains in the Americas from which they’ve successfully obtained DNA.

‘But the remarkable thing is that this rare type of DNA – which is only found in 2 per cent of Native Americans overall –

matched 20 per cent of the samples I had taken from Chumash Indians, here in California.

‘And when we looked at a wider database of all Native Americans, we found that this type was also in southern Alaska, in north-west

Mexico, in coastal Ecuador, in southern Chile, in southern Patagonia, and in prehistoric burials in Tierra del Fuego. All

the way down the Pacific coast.’

‘So do you think this is evidence for a coastal dispersal?’ I asked.

‘I think it is the best evidence to date for an ancient coastal migration: it suggests that this particular group gradually

moved down the Pacific coast, taking advantage of coastal resources, and left behind descendants who still live in all of

these areas.’

John and his colleagues had looked at samples from 584 Native Americans, from a geographical perspective. Haplogroup A was

more common along the coast, but there was also a rare subgroup of haplogroup D that seemed to echo a migration into the Americas

all the way down the Pacific coast of North and South America.

5

,

6

This was the same rare type that had been found in DNA extracted from the ancient tooth discovered on Prince of Wales Island,

in Alaska.

7

A recent study of Native American autosomal DNA markers – within chromosomes in the nucleus – also revealed a pattern, not

only of decreasing diversity from north to south, indicating colonisation in that direction, but also suggesting that the

coastal route was important.

8

Just possibly Arlington Woman may have been a descendant of the first ocean-going, beachcombing Americans.