The Incredible Human Journey (37 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

Leaving Oase, Silviu and I drove back to Bucharest, where I would be able to see the skull and mandible. We had travelled

close to the Danube on the way out to Oase, but on the way back we took a route through the beautiful wooded gorges of the

Carpathians. Where the gorges opened out into valleys, fields were visible in which people were cutting hay and heaping it

on to three-legged wooden frames to make stacks. The haystacks varied from field to field and village to village. Some were

tall and thin, others squat and conical. We slowed down to pass a heavily laden hay cart pulled by two horses.

The centres of the villages were often lined with low, terraced cottages, but on the outskirts there were more often than

not massive, ugly tower blocks. These buildings seemed so incongruous among the fields. ‘Why build blocks of flats in villages?’

I asked Silviu. ‘They were built by

Ceauşescu

,’ he said. ‘He wanted to create more land for farming.’ ‘But it seems like there’s

plenty of land,’ I suggested. ‘Yes. There is.

Ceauşescu

wanted to destroy the villages.’ It was strange to think that it

really wasn’t that long ago – 1989 – that

Ceauşescu

had been removed from power.

Romania was a country in recovery.

Silviu told me about how he had travelled around the countryside as a young man. He recounted how, if he’d got stuck for somewhere

to stay overnight, he would find a barn and sleep in the hay. He usually looked for someone to ask beforehand, and had often

been invited in to dinner. ‘People treated the occasional backpacker as a traveller: to be given hospitality,’ he said. ‘Now

they want money. They think tourists have money and they want some of it.’ Silviu was worried about the people and the countryside

being spoilt by tourism. He liked the wilderness.

‘What would this landscape have looked like 40,000 years ago?’ I asked Silviu.

‘I don’t know,’ he said, and paused for thought. ‘It would have been [Oxygen Isotope] Stage 3. So – colder than now. And wetter

summers. Like – perhaps Norway today, at the coast; maybe like Bergen.’

I tried to imagine the hunter-gatherers in the foothills of the Carpathians, dressed warmly against the cold, in a country

with red deer, ibex, wolves and cave bears. Although cave bears are long gone, there are plenty of brown bears roaming Romania

today: nearly half of all European bears are in the Carpathians. Some hunting of bears goes on today; indeed, one restaurant

in Bucharest even had ‘bear paw’ on the menu. There were times when I was truly glad to be vegetarian.

The following day, I visited Silviu in his natural habitat at the Emil Racovita Institut de Speologie in Bucharest. He brought

a series of cardboard boxes into a lab next to his office and we carefully unpacked some of the Oase bones. There were pieces of animal bone embedded in speleothem – a real gift for a geologist like Silviu who could date the

stalagmite, and therefore the bone. He also brought out a huge and formidable looking cave bear skull. And then there were

the human remains: the mandible and the skull.

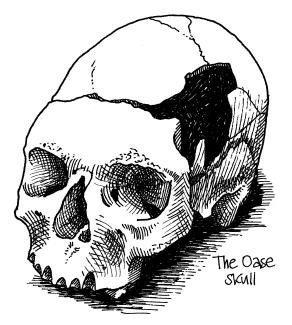

Again, these were quite clearly modern human. The skull was globular in shape, without any of the more obvious features of

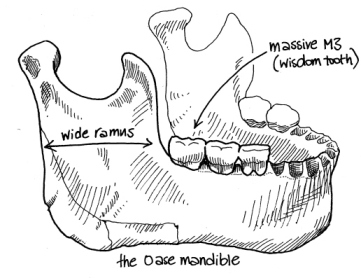

an archaic skull, like big browridges, or a protruding occiput at the back of the head. The jaw was quite gracile and modern-looking

too, with a definite chin. But there were some oddities – particularly in the mandible or jawbone. The chin was very straight,

the ramus (the part of the mandible ascending up to the jaw joint) was very wide, and the mandibular foramen (the hole on

the inside of the ramus where the nerve supplying the lower teeth enters) was a little strange. Then there were the teeth,

set in a very wide arc in the mandible, and with absolutely enormous wisdom teeth. These molars are usually smaller than

the ones in front, but in the Oase jaw they were huge.

1

,

2

I had read about these odd features in the scientific articles announcing the discovery and dating of the Oase bones, but

it was something entirely different to hold the actual bones in my hands and look at them myself.

Now, everyone is unique and we all have ‘anatomical traits’ – little variations on a theme – in our bodies and our bones.

In our skulls, some of us may have one hole for a particular nerve, where others have two or three. We might have little islands

of bone, or ‘ossicles’, embedded in the zigzag joins or sutures where the plates of the skull come together. Some of these

traits are genetic, whereas others appear during our lifetimes, and might be related to diet – or other things we do to our

bodies. For instance, lumpy bits of bone inside the ‘external auditory meatus’ – the bony part of the ear canal – can be caused

by swimming in very cold water. But, like skull shape and size generally, we’re not sure about how or why some of these traits

occur, and the various influences of genes and environment. It’s all part of that great question in developmental biology: how are our bodies shaped by our genes and our environment?

Having said all that, however, there are traits that do at least seem to hark back to an ‘earlier’ form. If you were being

unkind, you might call them ‘throwbacks’. If you were a bit nicer about it, you might think of these characteristics as echoes

of evolutionary history, glimpses of where we’ve come from. And those odd traits in the Oase jaw seem to fall into this category:

archaic features. But could this be more than just an echo of a more distant evolutionary past in these 40,000-year-old bones?

Is it possible that, instead, the Oase bones show a mixture of modern and archaic traits because that person

was

a mixture of a modern and an archaic human – some sort of hybrid? This isn’t such a preposterous idea, because, when modern

humans started making their way into Europe, someone else was already there: the Neanderthals.

As we have seen from the archaeology and fossil record of East Asia, ours was not the first human foray out of Africa. A series

of archaic human species made the leap before us.

In a review article that appeared in

Science

in 2003, Ann Gibbons wrote: ‘The long-legged, relatively big-brained hominin called

Homo erectus

has long been considered the Moses of the human family – the species that led the first exodus out of Africa more than 1.5

million years ago.’

3

The biblical analogy is great. I can imagine that striding, big-browed man leading his people out of Africa, across the Red

Sea, but it’s a sleight of pen in two ways. Firstly, there’s a wry and unwritten ‘but of course it wasn’t like that’, as we

all have this tendency to promote our ancestors to heroes and imagine their lives as epic struggles against adversity, winning

through so that we could be alive today. And secondly, Ann Gibbons goes on to write about

Homo georgicus

, one of the recent and somewhat cheeky surprises in European palaeoanthropology. The three paradigm-nudging and diminutive

fossil skulls were recently discovered in Dmanisi in Georgia, and dated to 1.75 million years ago. Then another small skull

was found in Kenya, dating to about 1.5 million years ago – perhaps belonging to a particularly small population of

Homo erectus

, perhaps linked with the Georgian hominins. The Kenyan skulls were the same age as another famous fossil: Turkana Boy. This

young man, with a largish brain, is sometimes classified as

Homo erectus

, sometimes as

Homo

ergaster

. (Remember that the world of palaeoanthropology is interpreted differently by ‘lumpers’ and ‘splitters’ – see page 3.)

Fossils can be extraordinarily slippery when you’re trying to pin a species name on them. The Kenyan and Dmanisi skulls are

no exception. They all look a bit like a small

Homo erectus

without browridges, but also bear similarities to another, earlier hominin species,

Homo habilis

. Although the discoverers of the Dmanisi skulls claim that they warrant a new species name,

Homo georgicus

, most researchers place the skulls in

Homo erectus

. So maybe

erectus

was the first hominin to get out of Africa after all.

3

Georgia lies west of the Caspian Sea, but it is hard to know whether it really counts as part of Europe or Asia. Certainly,

Dmanisi was sidelined when another, intriguingly ancient fossil, this time from the Sierra de Atapuerca, in northern Spain,

was reported as ‘The first hominin of Europe’. It dated to 1.2 million years ago, and its discoverers suggested that it was

Homo antecessor

(a category that some lump into

Homo heidelbergensis

).

4

By about 300,000 years ago,

Homo heidelbergensis

in Europe had morphed into Neanderthals. And when modern humans got to Europe, these other hominins, their distant cousins,

were still around in the landscape.

5

,

6

The first fossil of these ancient Europeans was found in 1848, in Gibraltar, but nobody paid it much attention. The bones

that gave the species its name were found in 1856 in Germany, near Düsseldorf – in the Neander Valley, or Neanderthal. The

valley was being quarried for limestone, and workmen clearing out mud from caves in the cliffs prior to quarrying found what

they thought were cave bear bones. But a local teacher recognised that they were human and collected them up.

7

The following year, rather bravely for the time, Professor Schaafhausen of Bonn University published a report on the skull

and bones from the Neander Valley, saying that they were normal – non-pathological – but seemed to be from an ancient inhabitant

of Europe as the remains were found alongside bones of extinct animals. This interpretation was challenged by Professor Mayer,

also at Bonn, who said the bones were probably much more recent, probably those of a Russian Cossack dying from rickets who

had crawled into the cave, with great browridges from frowning in agony. But a few years later the find had been widely published,

and there was a growing consensus that the bones were very ancient. The Irish anatomist William King proposed that the skeleton

should be given a new species name:

Homo neanderthalensis

. It was the first known species of a fossil human.

7

,

8

,

9

Since the discovery of the first Neanderthal fossil more than 150 years ago, several thousand bones have been found from more

than seventy different sites. And there are over three hundred sites where Neanderthal stone tools have been found.

Neanderthal characteristics start to appear in European

Homo

heidelbergensis

. For instance, the Sima de los Huesos specimens from Atapuerca, which are over 350,000 years old, already have some ‘Neanderthal’

features such as protruding faces and gaps behind their wisdom teeth, as well as a characteristic shape of the browridge,

and a ridge across the back of the head: the ‘occipital torus’.

10

By about 130,000 years ago, ‘classic’ Neanderthals

,

with full-blown features, lived right across Europe – and beyond.

11

Their territory extended from Portugal in the west to Siberia

12

in the east, from Wales in the north to Israel in the south.

And they persisted in some parts of Europe and western Asia until less than 30,000 years ago –

after

modern humans had arrived in Europe.