The Illustrious Dead (4 page)

Read The Illustrious Dead Online

Authors: Stephan Talty

Tags: #Biological History, #European History, #Science History, #Military History, #France, #Science

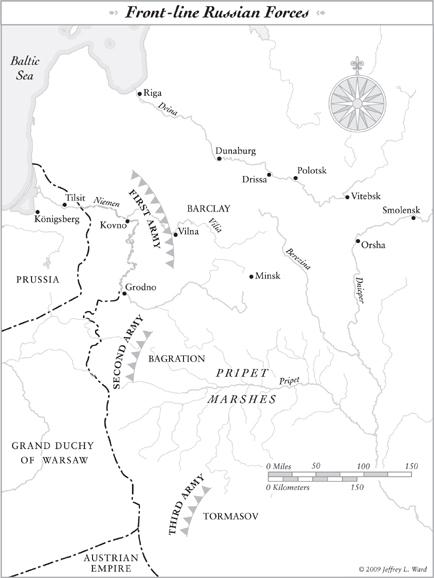

The Russian army was divided into two forces. General Mikhail Barclay de Tolly led 160,000 men of the First Army in a line opposed to Napoleon’s northern positions. Barclay was an unspectacular but highly competent general, a straight-backed, balding, reserved man who suffered from several disadvantages in the position and historical moment he found himself in: He was descended from a Scottish clan and spoke German as his first language, deeply suspect credentials for a man defending a country that was whipping itself into a nationalist fervor. And although he had made his name in a thrilling battle during the 1809 Finnish war by marching his army over the frozen Gulf of Bothnia, an exploit worthy of the young Napoleon, he was conservative by nature.

The man who would quickly emerge to be his closest rival was General Pyotr Bagration, a hot-tempered nationalist eager for a confrontation with Napoleon. Bagration commanded the 60,000 troops of the Second Army, which would face the French positions in the south. Four years younger than Barclay, he was a firebrand, tetchy, capable of plunging into ecstasies of despair or joy depending on the progress of the battle (and of his career). He was as ambitious for himself as he was for his nation, and in his deeply emotional responses to the progress of the war, he would prove to have an innate understanding of the Russian mind that the phlegmatic Barclay often lacked.

Napoleon planned to drive between them east along the Orsha-Smolensk-Vitebsk land bridge, which would lead him almost directly due east toward Moscow, should he need to go that far. His plans were straightforward: keep the two armies separated; drive forward and encircle them separately; cut off their supply, communication, and reinforcement lines to the east; force them into a defensive posture near Grodno; and then annihilate them. Napoleon continued to believe that Alexander would sue for peace after a convincing French victory.

But in one respect Napoleon had radically misjudged Alexander. He was thinking in terms of empire. Alexander was mobilizing his people for another kind of conflict entirely. The tsar was convinced he was facing an Antichrist, a millennial figure who would destroy Russia itself. For him, the coming war was a religious crusade.

T

WO ANCIENT WARS

set the stage for the kind of conflicts the two men planned for and mark the vicious debut of the lethal pathogen that was already deeply embedded in the Grande Armée.

In 1489 the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella fought a decisive battle with the Islamic forces of the Moors. The Moors had ruled Spain ever since crossing the Strait of Gibraltar in

A.D.

711, leaving only a few lonely outposts of Christians in the north of Spain along the Bay of Biscay. The Christian warriors bided their time, taking advantage of dissension among the Muslim rulers, looking to the Crusades for inspiration in their slow war of toppling one Islamic stronghold after another. By the late 1400s, only the citadel of Granada was left.

During the siege of the city in 1489, a third combatant entered the field: a “malignant spotted fever” began carrying off Spanish soldiers at a fast clip. When the Catholic forces mustered their soldiers in the early days of 1490 to regroup, their commanders were shocked to learn that 20,000 of their men had gone missing. Only 3,000 had fallen in battle with the Moors, meaning that a full 17,000 had died of the mysterious disease. In an age when small armies of 30,000 to 40,000 were the rule, that figure represented a devastating loss of fighting power.

But this was the illness’s first foray into war, and it didn’t have the decision-changing impact it would later carry. The Spanish recruited more soldiers to replenish their ranks and returned to the campaign. On January 2, 1492, the last Muslim ruler of Granada, Abu ’abd Allah Muhammad XI, departed the ancient province and left Spain to the Christians. January 2 remains a black day in the minds of Islamicists today.

Ferdinand and Isabella had fought a religious war in the context of empire (or, equally true, a war of empire in the context of religion). It was a template that fit Alexander’s view of the battle to come. The Spaniards had overcome the fatal disease that struck their armies primarily by luck and persistence: The battles were being fought on their territory, meaning their commanders could quickly replace troops lost in the epidemic. Alexander, whose religious mania exceeded that of the Spanish king and queen, would have the same advantage against the despoiler from France.

F

ORTY YEARS LATER, THE MALADY

that would meet the emperor on the road to Moscow emerged from the shadows to fulfill its role as an arbiter of empires.

The conflict drew together the depressive King Charles of Spain, the greatest power on the Continent; King Francis I of France, a young ruler who wished to retrieve ancestral lands claimed by Charles (and his two sons, held for ransom in a previous war); and King Henry VIII of England, who had territorial ambitions in the war but also sought, by taking control of Italy and Rome, to gain control over Pope Clement VII and to obtain a divorce from Catherine of Aragon so that he could marry Anne Boleyn. Drawing in the continent’s three most powerful monarchs, this was a war for control of Europe’s future.

King Charles expressed the ethos of the war they would fight. It was a contest between honorable knights, and Charles longed to live up to the code they shared:

Therefore I cannot but see and feel that time is passing, and I with it, and yet I would not like to go without performing some great action to serve as a monument to my name. What is lost today will not be found tomorrow and I have done nothing so far to cover myself with glory.

It was a passage that Napoleon could have written nearly three centuries later.

In 1527 the forces of King Francis (bolstered by a contingent from Henry VIII) met Charles’s mercenary army at the Italian port city of Naples, the French army with 30,000 men, the Imperial army of Charles with 12,000. If Francis could destroy the army inside the walls, Spain’s power, so dominant for so long, would be broken at least for the near future and perhaps for centuries.

But then a pathogen appeared in the ranks and began to kill wantonly. “There originates a slight internal fever in the person’s body,” wrote one ambassador, who later died of the illness, “which at first does not seem to be very serious. But soon it reappears with a great fervor that immediately kills.” It was the same inscrutable microbe that had emerged at the Spanish siege of Granada.

Bodies began to pile up. The Italian sun beat down on men who had fallen into stupors or raving fevers. Each day brought more cases, and soon the sick began to die in terrible numbers. “The dangers of war are the least we have to think about,” wrote one commander. The French lieutenants, convinced the air in the plain had turned bad, urged their commander to retreat to the hills, where the atmosphere was cooler and fresher. But he refused and the epidemic “literally exploded.” Desertions increased; men faked illness to get out of the death zone. Out of a force of 30,000, only 7,000 were fit for duty. Soon two out of every three of the soldiers had died, most of them from the nameless pathogen.

At the end of August, the French forces broke from their camps and fled in panic, leaving their artillery and their sick comrades behind. The siege was broken. Charles’s forces ran them down on the road from Naples to Rome, stripping, robbing, and killing the remnants. “Without a doubt,” one observer wrote, “one would not find in all of ancient and modern history so devastating a ruin of such a flourishing army.” Francis’s men were skeletal, sick, some of them clothed only in tree leaves. The disease claimed more on the way and bodies could be seen heaped on the side of the road. Of the 5,000 who started the retreat, perhaps 200 arrived safely in the holy city; from there, some French troops were forced to walk all the way back to their native land.

The effects unspooled for years. Spain dominated the Continent, King Francis was humiliated and France radically weakened. Pope Clement VII rejected Henry VIII’s petition for divorce as a direct result of the defeat. Infuriated, the king broke with Rome and led his country into the Church of England.

Even today, a believer kneeling to pray in a High Anglican Church worships, at least partly, in a structure built by an invisible microbe.

The conflict revealed crucial aspects of the epidemic disease: It seemed to need large groups of people to thrive. It left dark spots on the torsos of many of its victims, sparing the hands and face (making it harder to detect in men who wore full uniforms). It had a terrifying mortality rate, up to

95

percent, among the highest of any epidemic disease known to humankind. And it had a decided predilection for war. It was almost as if nature had invented a biological sleeping agent to combat the wishes of ambitious men.

N

EARLY THREE HUNDRED YEARS

after the siege of Naples, Napoleon reclaimed Francis’s sword after conquering Spain and brought it back to Paris in glory. He’d revenged the monarch’s humiliation. And now Napoleon imagined he was about to embark on a war that would share in the same codes of war.

The historian David Bell has argued persuasively that in the years 1792-1815, the modern concept of “total war” came into being, ushered in by Enlightenment ideas about the perfectibility of society and the political upheavals that followed the French Revolution. The “culture of war” was transformed so that the struggle between France and the successive coalitions against it became, in the words of one French supporter, “a war to the death, which we will fight so as to destroy and annihilate all who attack us, or be destroyed ourselves.”

The description fits Alexander’s view of the coming battle. The transformation of national conflicts into all-out, apocalyptic duels, a notion that has come cleanly down to us as a clash of civilizations in which one side must win or die, would be realized on the road to Moscow. And there, as in the modern version, faith would play a huge role.

Certainly Napoleon endorsed such an all-encompassing view of war, especially early in his career. Still, he genuinely imagined the coming invasion would have certain limitations, especially in the endgame. He believed Alexander was a nobleman who would fight, be measured on the battlefield, and then settle according to the results of arms, as had Francis I and Charles of Spain. The emperor had badly misjudged the situation in Russia.

But his war machine made the error seem irrelevant. If ever there had been an armed force built for total, annihilating war, it was the Grande Armée. No divisions on earth, arrayed against it in a straight-ahead confrontation, had a remote chance of winning.

Except if they had a hidden, undetectable ally in the fever that had burned at Naples.

C H A P T E R 3

Drumbeat

Drumbeat

A

S WAR APPROACHED, ADVISERS BEGAN TO WARN

N

APO

leon. His statistical expert, a Captain Leclerc, looked at the demographics and resources of Russian society and told the emperor that, if he invaded, his army would be “annihilated.” Others recounted in detail the deprivations suffered by the last army to invade the Russian hinterland: that of the strapping and enigmatic Charles XII of Sweden, whose forces were almost completely wiped out by cold, Cossacks, and disease in 1709. Charles would come to haunt Napoleon, as he paged through Voltaire’s history of the campaign on his way to Moscow. But more and more a smashing victory seemed an answer to Napoleon’s problems. By the first months of 1811, the emperor had ordered his Topographical Department to supply him with accurate maps of western Russia.

Early in 1811, Napoleon assured both his advisers and Alexander’s representatives that his intentions were peaceful. “It would be a crime on my part,” he told Prince Shuvalov in May, “for I would be making war without a purpose, and I have not yet, thank God, lost my head. I am not mad.” But he contradicted himself by returning to the language of threat and provocation again and again. Indecision, which would plague every phase of his conduct of the war, also muddied his thinking when it came to starting it.

The first unit to move on his command was a Polish cavalry regiment, which left Spain on January 8, 1812. On January 13, Napoleon ordered his War Administration department to be ready to provision an army of 400,000 frontline troops for fifty days. That broke down to 20 million rations of bread and 20 million rations of rice, along with 2 million bushels of oats for the horses and oxen. Some 6,000 wagons, either horse-or ox-drawn, were requisitioned to carry enough flour for 200,000 men for two months. The customary card index, which Napoleon kept on all opposing armies, detailing strengths and weaknesses down to the battalion level, was quickly pulled together.

The emperor wrote Alexander on February 28, 1812, warning him to abide by the Continental System or face dire consequences, a threat that Alexander brushed off by saying he was only protecting Russian business interests. Alexander included a list of demands required for his return to the Continental System, including a French evacuation of Prussia, which Napoleon regarded as impertinent. The emperor railed at his advisers and predicted that a prospective war would last only twelve days. “I have come to finish once and for all with the colossus of Northern barbarism,” he shouted. Napoleon’s advisers were horrified. He had never approached a campaign with so few backing opinions from those around him.

“Whether he triumphs or succumbs,” observed the German-Austrian diplomat Count von Metternich, “in either case the situation in Europe will never be the same again.” The emperor ratcheted up the rhetoric against Alexander, and he began to embroider his vision of a quick war with grand designs: if the tsar fell or was assassinated, the Grande Armée could pivot south and march to the Ganges, taking India and its rich markets and dealing a crushing blow to English maritime commerce, crippling the trade that funded the British Empire. Napoleon was wandering even deeper into self-delusion.

The emperor wasn’t the same man he had been ten years before. He had grown stout, his skin had turned sallow, the lean, hawklike face had developed the hint of jowls, and his almost forbiddingly intense expressions had mellowed and grown more querulous. “He spoke more slowly and took longer to make decisions,” writes historian Adam Zamoyski. “Something was eating away at the vital force of this Promethean creature.” Whether this decline was caused by the effects of middle age or physiological problems, but Napoleon was a less commanding figure, physically and intellectually, just as he began his most exhausting mission.

I

N

R

USSIA, THE CALLS

for war escalated almost monthly. The country was, in its own way, deeply imperialistic, a rising power probing west (in Sweden) and south (toward the increasingly feeble Ottoman Empire) for new sources of wealth and territory. Its upper classes and its army officer corps were fluent in French, the only language many of them spoke, and their bookshelves were lined with volumes of Voltaire and Montesquieu. Still, they deeply resented Napoleon’s encroachment upon Russian power and national pride.

As rumors of war spread, waves of revolt rippled through the society. French tutors lost their jobs and it became fashionable for boyars and aristocrats to spice their conversations with Russian phrases. When Alexander appeared on the Kremlin’s Red Steps, he was greeted by thousands of ordinary Russians shouting, “We will die or conquer!”

In the early months of 1812, Napoleon’s armies began streaming toward the Polish border from France, Italy, Hungary, and other garrisons. Even the Austrians and Prussians were forced to contribute 30,000 and 20,000 men, respectively, to face their former ally. Napoleon had clearly made up his mind on war, though he kept his target a secret from the general public and even his own marshals.

But Alexander stole a march on the emperor. In quick succession, he formed an alliance with his old adversaries the Swedes in the north and signed a peace treaty with the Ottoman Turks in the south, securing his most troublesome borders and eliminating the possible division of his armies for war on two fronts. Napoleon meanwhile dithered and made a halfhearted attempt to sign a treaty with the British in Spain, without, however, offering much of anything to end a disastrous war. The British sensibly refused. In the months before the Moscow campaign, it was Alexander who looked like the master political player and Napoleon who looked like a distracted novice.

O

N

M

AY

9, 1812, the emperor left Paris and began a processional through his client kingdoms, a display of his wealth and power that he’d remember as the happiest time of his life. He traveled with an army of 300 carriages filled with crystal, plate, tapestries, and his own personal furniture, sweeping into the king of Saxony’s castle and putting hundreds of chefs to work creating a Pan-European menu that was testament to his reach. Nobles, kings, and queens came to pay homage.

The German poet Heinrich Heine remarked on how the army’s veterans, passing in review before the emperor, “glanced up at him with so awesome a devotion, so sympathetic an earnestness, with the pride of death.” The army itself was a pageant, gaily outfitted in all the colors of the peacock. Cuirassiers, the cavalrymen who were the successors of medieval knights, pranced on their chargers, their mirrorlike steel helmets capped by black horsehair manes. The carabiniers were dressed in crisp white jackets, while the lancers wore crimson shapkas with white plumes a foot and a half high. The rapid-response chasseurs wore kolbachs with green and blood-red feathers, while the hussars strutted in their tall peaked shakos topped with red feathers. Dragoons sported turbans cut out of tiger skin and brilliant red coats, and the grenadiers of Napoleon’s elite unit, the Imperial Guard, wore the traditional French blue uniform covered by great bearskins, the sun glinting off their gold earrings.

A

S MORE AND MORE

units from the empire marched toward the Niemen River to assemble for the invasion, in Germany one of the millions who would be deeply affected by Napoleon’s decisions prepared to leave. Franz Roeder was a captain in the First Battalion of the Lifeguards of the Grand Duke of Hesse, a German principality. Roeder was typical of the soldiers who would form the core of any assault on Russia: he was non-French; experienced in battle, having nearly died in the Russo-Prussian War; and fiercely loyal to his men and his reputation, if not to the emperor. Roeder was handsome, with a long aquiline nose, an intense gaze, wavy hair that fell over his collar, and a mouth that seemed to be holding back some outrageous remark. He had entered the barracks after punching a schoolmaster as a boy and running from a flogging, never to return. And as war approached, he was trying to get on with his life despite the rumbles from Paris. The captain expressed as well as any soldier readying for battle what it would mean in the terms of a single life.

For Roeder, the most pressing dilemmas were romantic: His beloved wife Mina, a direct descendant of Martin Luther, had died of consumption that year and he was left with two young children to care for. Still steeped in grief, he was nevertheless thinking of asking a young woman named Sophie, who lived in a city miles from his hometown, to marry him. His children needed a mother, and he, in his loneliness, needed someone to love. Letters and short visits added up to a courtship against the gathering clouds.

As Napoleon rattled his saber, Roeder read the signs. “Nobody believes that it will really come to war,” he wrote in his diary. “This hope helps the good souls to overcome the pain of parting and obscures for them the danger which looms so close, which may well lead, not to long absence, but to parting forever.” One night, feeling a departure approaching, he rushed to the neighboring town where Sophie lived, pulled her out of the opera between the second and third acts, and asked her to marry him. He didn’t even have a ring to offer her, but she said yes. The veteran campaigner was relieved. At least the children, if he died, wouldn’t be orphans.

B

Y

A

PRIL

, C

APTAIN

R

OEDER

was marching his 181 men through the roads of eastern Germany. In the bigger towns, his men were feted at balls, and Roeder, although just married to a new wife and haunted by a dead one, flirted with the local beauties. His men were mostly healthy but suffering from diarrhea, “which may be partly caused by the water,” he wrote from the German town of Doberan, “through which they frequently have to march up to the knees.” A more worrying case was that of his quartermaster, who, on May 21, died of “creeping nervous fever,” most likely an early sign of the approaching epidemic.

But the general mood was good. “I share the thoughts of the whole army. It has never shown itself more impatient to run after fresh triumphs,” wrote Captain Louis-Florimond Fantin des Odoards, a veteran grenadier who had fought at Austerlitz and Friedland. “Its august leader has so accustomed it to fatigue, danger, and glory that a state of repose has become hateful. With such men we can conquer the world.” Roeder, too, despite his love for Sophie, relished being out with his men, throwing his cape under a tree and falling asleep under the stars. Many of the young recruits saw the 1812 campaign as the finale in a long link of adventures, the last chance for rapid advancement and glory. Some 10,000 wills were drawn up by Parisian notaries before the commencement of hostilities, and the famous coachbuilder Gros Jean churned out carriage after carriage for the marshals and generals.

· · ·

N

APOLEON PLANNED FOR

a spring/summer offensive that would allow the fields to ripen with oats for his horses and wheat for his men. As he attended to the thousands of details necessary for a campaign involving half a million troops and more, he made a shocking discovery. His much-vaunted medical service was in disarray, with even the basic necessities for a campaign—dressings, linens, splints—in short supply. His surgeon in chief, the legendary Dr. Dominique-Jean Larrey, rushed from Paris to Mentz, Germany. But the forty-six-year-old surgeon was being sent “doctors” so inexperienced that he was forced to give them crash courses in battlefield medicine.

Despite Larrey’s sterling reputation (“the worthiest man I know,” the emperor once said), Napoleon didn’t trust doctors. He could be progressive when it came to new techniques, such as Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine, discovered in 1796, which the emperor embraced, even having his two-month-old son inoculated and spearheading a vaccination campaign for the young and new army recruits. But for the most part he despised physicians, shouting at his guests “Medicine is the science of assassins!” during one memorable party. He was a fatalist when it came to epidemics. He believed that if one wasn’t strong enough to resist disease, it would claim you. Mental fortitude was the only remedy.

These attitudes were rooted in Napoleon’s youth. At the age of twenty, while walking across the Ajaccio salt flats near his birthplace, he’d come down with a serious fever, but he had survived with no aftereffects. While stationed in Auxonne as a poverty-stricken junior officer, Napoleon had survived a bout of malaria while still managing to put in eighteen hours of study every day. A second wave hit after the first had subsided, and Napoleon blamed it on the

miasme

(or “bad air”) from a river close to his lodgings. Still, he worked furiously through the headaches and pain. “I have no other resource but work,” he wrote. “I dress but once in eight days; I sleep but little since my illness; it is incredible.” For the young Corsican—penniless, friendless, obscure but driven—those days were his refining fire. Disease had been just another test. Why couldn’t other men overcome it?

Instead of physicians he believed in portents, lucky omens, as any true Corsican of the time would have. March 20 and June 14 were particularly good days for him; he hated Fridays and the number 13. He had a “familiar” called Red Man, a conduit to his lucky star, which visited him only on important occasions. In Egypt, the Red Man had told him that success was guaranteed despite his reversals, and in Italy, at Marengo, the spirit assured him that he was soon to be emperor of France. As he contemplated the invasion of Russia, the ghost had appeared to him and told him the war was a mistake, but after considering the warning, he disobeyed. To rebel even against the spirit world would prove he was equal to the gods themselves. “I’m trying to rise above myself,” he confided to his officers on the campaign. “That’s what greatness means.”