The Illustrious Dead (24 page)

Read The Illustrious Dead Online

Authors: Stephan Talty

Tags: #Biological History, #European History, #Science History, #Military History, #France, #Science

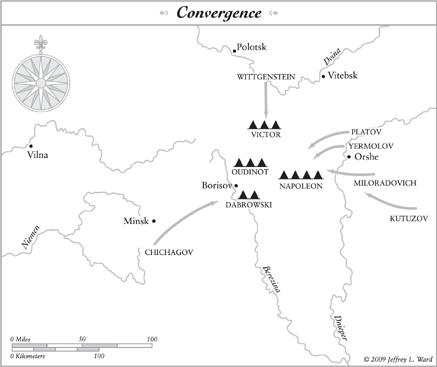

The various Russian armies—the headstrong Admiral Pavel Chichagov in the southwest, Wittgenstein in the north, and remains of the First and Second armies along with the Cossacks tailing Napoleon—were all poised to converge at Borisov. The depots at Minsk had already fallen to Chichagov’s 60,000 men. All signs pointed toward a Russian pincer movement at the river, where Kutuzov would spring his long-delayed trap and annihilate the French army before it could escape to Lithuania and the Niemen.

“Kutuzov is leaving me alone now in order to head me off and attack me,” Napoleon said. “We must hurry.” He knew there was only a single bridge at Borisov, guarded by a single Polish division. If the Grande Armée didn’t reach it in time, they could find their way blocked and their escape thwarted. In one of the statements that give the measure of Napoleon’s sangfroid, he remarked, “This is beginning to be very serious.” It had, of course, been serious for many weeks, but Kutuzov’s incompetence as a strategist and as a fighter gave the emperor some hope of outmaneuvering the Russians. Still, the numbers and the terrain were wholly in favor of the enemy.

Napoleon didn’t realize he’d been beaten to the choke point by Lambert’s men. The Russians, believing their lines secure, then found shelter and relaxed their guard. Unknown to them, French troops were streaming toward the city, and when they arrived they found the Russians unprepared for an attack. The fighting was savage but one-sided: the Russians lost 9,000 men and in their negligence would have handed Napoleon a golden opportunity to slip over the Berezina unmolested had they not torched the single bridge as they fled to the western bank. The river, packed with mushy, unstable ice, was effectively unfordable. New bridges would have to be built under the guns of the Russians and the old one quickly repaired.

On November 23, the French command received the news while they were just under forty miles from the Berezina. Napoleon briefly considered a thrust northward to surprise Wittgenstein’s army and then a turn west. But the roads were unfamiliar, the terrain was marshy and rough, and his troops were in no condition for the maneuver. Instead he decided to race to Borisov and attempt to rebuild the destroyed span, throw some pontoon bridges across the river, and get away before Kutuzov could smash his forces against the icy water. “The names ‘Chichagov’ and ‘Berezina’ passed from mouth to mouth,” remembered Captain Johann von Borcke. The lead elements of the French forces arrived in Borisov on November 23, with Napoleon a day behind. The engineers tasked with building pontoons for the thousands of troops rushing up behind them gaped at the currents sweeping great tumbling chunks of ice downstream.

But French cavalry units had stumbled on a point in the river seven miles upstream that the army might be able to ford en masse. Their general lobbied Napoleon to change course and head for the crossing point. If the army could ford the Berezina there, Napoleon might be able to squeeze his armies between Chichagov in the south and Wittgenstein in the north instead of fighting his way through.

Bad information and the lack of coordination among the Russian commanders allowed the French this small window of opportunity. As Napoleon made his move northward, Chichagov was receiving contrary reports about the French intentions. His scouts reported sighting enemy units below Borisov, and bulletins from both Kutuzov and Wittgenstein warning him of a possible attack on his southern flank, combined with eyewitness reports from villagers of Frenchmen gathering logs and other bridge-building materials in the area, confirmed the impression that Napoleon intended to ford the river

below

the town. He stationed 1,500 of his men in Borisov, then led the rest of his troops out of the town and turned due south. The log gatherers were actually cuirassiers sent on a jaunt to trick Chichagov. The ruse worked.

What should have been a classic pincer movement became a trap clattering open, at least momentarily. But it would still be a perilous escape. Knowing this, Napoleon burned the reports from Paris that had reached him on the retreat and created a new personal security detail, the “sacred squadron,” made up of 500 commissioned soldiers, to protect him from the very real possibility of becoming a prisoner of state.

The French troops hurried north and managed to get 750 sappers to the crossing point on November 24 to begin the construction of two bridges, one for the cavalry, wagons, and artillery and the other for the infantry. With them they had six wagons packed with essential materials that were almost abandoned earlier in the retreat: hammers, crowbars, and iron sheets, along with four wagons packed with coal and portable forges to make the nails and cross braces. Wood came from the huts and stables in the village, which were torn apart to provide planks; steel rims from the abandoned wagons were turned into clamps and spikes. Carrying them over their heads, the pontoneers walked out into the dangerously cold river, about a hundred feet wide and six feet deep at this point, their boots slipping over the smooth rocks on the river bottom. Fifteen minutes was all that any soldier could stand in the currents, and many succumbed to hypothermia or stumbled and were carried away by the river. The Dutch soldiers worked knowing that on the elevations across the river, Cossack pickets were patrolling the far banks, and their bobbing heads were easily within Russian cannon range.

The Cossacks spotted the pontoneers at their work, setting trestles in water up to their chins, and sent riders to Chichagov with reports of the suspicious activity. If the messengers returned with Chichagov’s main force, using the heights of the opposite bank to sweep the river with canister and musket fire, the Grande Armée would have been lost. But Chichagov, notorious for refusing to admit his mistakes, took the activity for a feint and stayed where he was, prowling the banks south of Borisov for a sign of Napoleon.

The emperor remained calm as the work progressed. Marshal Ney remarked that if Napoleon got the army out of this fix, he would never doubt the emperor’s luck again. But Murat, more high-strung than his colleague, bent under the strain, bursting in on Napoleon as he worked in a house on the riverbank. “I consider it impossible to cross here,” he burst out. “You must save yourself while there is still time!” The emperor brushed the suggestion aside as beneath him. He was eager to reach Paris, but abandoning the army at a choke point while the enemy lurked all around would have been a black mark on his name.

At dawn on November 26, the French watched the opposite bank, half expecting to see Chichagov’s ranks serried back from the water’s edge. Surely the incessant pounding of the sappers’ hammers and the shouts of the engineers had brought the main body of the general’s forces to the crossing point. But the light revealed only abandoned campfires and a black line of troops curling into the tree line on the road south to Borisov. “It isn’t possible!” Napoleon cried in astonishment. But it was. Chichagov had abandoned the position. The emperor sent 100 chasseurs and Polish lancers to drive off the handful of Cossacks left behind and later secured the bank with 400 troops ferried over on rafts.

By noon, the first bridge was finished. The second, intended for the cavalry and wagons, would take four more hours. Napoleon sent cavalry and infantry units across to cover the retreat’s southern flank, in case Chichagov changed his mind and moved northward. The Guard followed soon after, followed by the “sacred squadron” with Napoleon in its midst, then Davout, Ney, Murat, and Eugène. The men hurried across the rickety bridge, whose planks rested just inches above the water, with the trestles that anchored the bridge sometimes sinking under the weight of the troops, dipping the planks into the frigid water. Horses had to cross at intervals, for fear that their cumulative weight would collapse the “matchbox” structure. From the woods, the thousands of stragglers watched for their chance to make it across, their numbers growing as the hours passed. The wheels of the carriages, artillery pieces, and officers’ wagons rattled along the uneven roadway of the second bridge, scraping off the pine branches and horse dung that had been used as a surfacing material.

Trestles sank or tumbled over on both bridges, planks cracked, and sappers rushed back into the water to improvise a fix and keep the soldiers moving, bashing the ice floes away with their axes. The anxious men fought over their place in line, shoving each other back from the first planks. As the day progressed, a north wind picked up and snow began to fall, at first gently, then in sheets. Napoleon, dressed in his campaign uniform with white breeches and a gray overcoat, his boots freshly shined, watched from the shore.

The bulk of the army had made it to the western bank by evening on November 27. Only a few units and Marshal Victor’s brigades, who were arriving at the Berezina after battling Wittgenstein, remained. The military police who had guarded the entrance to the bridge and controlled the flow over it began letting the stragglers onto the structure, but they weren’t rushing to cross, not yet. There was no sign of a Russian attack and it was safer to cross the bridges, which increasingly sagged and buckled as the crossing went on, during daylight.

On the morning of November 28, the window began to close. A contingent of 30,000 Russian soldiers, sent north by Chichagov, encountered French forces on the western bank of the Berezina. Shells splintered trees and musket fire clipped off pine branches as the Russians pressed to close off the escape route toward Vilna. Ney rushed some of his 13,000 men as reinforcements, but Chichagov, now fully convinced that Napoleon had duped him, was sending his entire army north and the volume of enemy fire directed toward the French seemed to increase by the half hour.

The Grande Armée, bone-thin and riddled with disease, turned to stop the attack. Cries of “Vive l’Empereur!” echoed through the forest as Polish, Swiss, Croat, Portuguese, and Dutch troops held off the numerically superior Russians. When the Swiss regiments ran out of ammunition, they leveled their bayonets and plunged through the knee-deep snow, scattering the Russian infantry as they went. One Swiss soldier, Louis de Bourmann, was advancing with his 2nd Regiment when an officer dismounted ahead of him to lead his men on foot. “A Russian musket ball went through his throat,” recalled one of his men. “He gave a cry, stifled by blood, and fell backwards into my arms…. Without losing consciousness, he said these simple words to his fellow-citizen: ‘Bourmann, I’ve died here as a Christian.’” The soldiers’ efforts stood out on one of the Grande Armée’s finest days. The Swiss charged the Russians seven times with only bayonets to defend themselves. The mysterious bond that held Napoleon’s army together despite every incentive to disintegrate held fast.

At the same time, Wittgenstein was descending on Victor’s men on the eastern bank, the long-awaited pincer finally closing on the French. Wittgenstein had already rolled up one of the brigades that had held Borisov until November 27, then blundered north into the Russian lines. Now he concentrated an artillery barrage against the 8,000 remaining troops and the mini-city of stragglers and human flotsam that huddled amidst the gray smoke of the campfires. Rumors had been circulating since three in the morning that an attack on the rear guard was imminent, and the entrance to the first bridge had become jammed with thousands of men, women, and children desperate to avoid being captured and being sent to camps in the frozen North.

The bombardment only increased the frenzy. The mass of people rippled and surged, throwing men into the icy river and packing the crowd so tightly that no one could move forward or back. One was simply carried along, feet never touching the bridge. Karl von Suckow of the Württemburg III Corps found himself “surrounded on all sides, caught in a veritable human vise…. Everyone was shouting, swearing, weeping, and trying to hit out at his neighbors.” The road leading to the bridge became littered with corpses of men and horses, their flesh pulverized under the hordes pressing toward the river. All the while Russian round shot struck the crowd, leaving craters of mud and severed limbs. The stragglers rushed from one bridge to the other, battling crowds headed in the other direction.