The Illusion of Conscious Will (31 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

A telling example of this postbehavioral intention construction process was provided in a study by Kruglanski, Alon, and Lewis (1972). For this research, elementary school students were asked to play a series of group games, and the winners were either given a prize afterwards or were not. Normally, if the students had known about the prize in advance, this would have been expected to introduce a reduction in reported enjoyment of the games. Both dissonance and self-perception theories would predict that doing something for a known prize would lead the students to say that they liked the activity itself somewhat less. However, in this experiment, there was no actual mention of the prize in advance of the games. Instead, the experimenters told the prize group after they had won the games, “As we said before, members of the winning team will be awarded special prizes as tokens of their victory.” In essence, then, although the prize was a

fait accompli,

an unexpected consequence of the action, the prize winners were given to believe that this surprise was something they might have known all along. And under this misapprehension, students in the prize group indeed showed a reduction in their reported enjoyment of the games. The revision of intention (“I didn’t really want to play those games”) took place when people were hood-winked into thinking that they had known the consequences of their action in advance.

The processes that operate during the confabulation of intention are fallible, then, just like most human judgment. When people learn that they might have known or ought to have known of a consequence of their action, they go about revising their attitudes and intentions as though they actually did know this beforehand. The process of intention revision, in short, is a process of fabrication that depends on an

image

of ourselves as responsible agents who choose our actions with foreknowledge and in accord with our conscious intentions. Although such an agent may not actually animate our intention and action, an idealized image of this agent certainly serves as a guide for our invented intention. When we look back at our behavior and believe that the circumstances surrounding it are compatible with seeing ourselves acting as agents, we construct—in view of what we have done—the intention that such an agent must have had. Then we assume that we must have had that intention all along.

The post hoc invention of intentions can lead us away from accurate self-understanding. In the process of confabulating intentions, we may concoct ideas of what we were trying to do that then actually cloud what-ever insight we do have into the causes of our action (Wilson 1985; Wilson and Stone 1985). Normally, for instance, the ratings people make of how much they like each of five puzzles they have done are strongly related to the amount of time they spent playing with each one. However, when people are asked to write down the reasons they like or dislike each of the puzzles, their later ratings of liking are far less related to actual playing time (Wilson et al. 1984). The process of analyzing reasons—or what Wilson (1985) calls “priming the explanatory system”—can even bend preferences awry and lead people to make bad decisions. In research by Wilson and Schooler (1991), for example, students who analyzed why they liked or disliked a series of different strawberry jams were found to make ratings that agreed less with experts’ opinions of the jams than did those who reported their likes and dislikes without giving reasons. It is as though reflecting on the reasons for our actions can prompt us to include stray, misleading, and nonoptimal information in our postaction assessments of why we have done things. We become less true to ourselves and also to the unconscious realities that led to our behavior in the first place. The process of self-perception is by no means a perfect one; the intentions we confabulate can depart radically from any truth about the mechanisms that caused our behavior.

Left Brain Interpreter

Much of the evidence we have seen on the confabulation of intention in adults comes from normal people who are led by circumstance into periods of clouded intention. With behavior caused by unconscious processes, they don’t have good mental previews of what they have done, so they then appear to offer reports of pre-act intentions they could not have had in advance. The role of the brain in this process is brought into relief by the very telling lapses of this kind found in people who have experienced brain damage—in particular, damage that separates the brain sources of behavior causation from the brain sources of behavior interpretation. This work by Michael Gazzaniga (Gazzaniga 1983; 1988; 1995; Gazzaniga and LeDoux 1978) suggests that the left brain interprets behavior in normal adults.

These studies began as investigations of the abilities of people who have had their left and right brains surgically severed by partial or complete section of the corpus callosum as a treatment for severe seizures. Such treatment leaves mid and lower brain structures joining the two sides intact but creates a “split brain” at the cortex. Animal research had shown that this yields a lateralization of certain abilities—the capacity to do something with one side of the body but not the other (e.g., Sperry 1961). The analysis of the separate talents of the sides of the brain can be achieved in human beings, then, by taking advantage of the fact that inputs can be made and responses observed for each side of the brain separately. For inputs, tactile material presented to one hand or visual material shown quickly on one side of the visual field (too fast to allow eye movement), stimulates the opposite or contralateral brain hemisphere. Responses then made by that hand are generated by the contralateral hemisphere as well. With these separate lines of communication to the two hemispheres, it was soon learned that verbal responses are generated exclusively by the left hemisphere in most patients studied. Material presented to the right brain does not usually stimulate speech.

The few exceptions to this rule provide the key cases for observations of left brain involvement in intention plasticity. A patient identified as J. W., for instance, had sufficient verbal ability in the right hemisphere to be able to understand and follow simple instructions. When the word

laugh

was flashed to the left visual field, and so to the right brain, he would often laugh. Prior study had determined, however, that his right brain was not sufficiently verbal to be able to process and understand sentences or even make simple categorizations. Thus, when he was asked by the investigator why he had laughed, it was clear that any response to this sophisticated query would necessarily have to come from the left brain. What J. W. said was, “You guys come up and test us every month. What a way to make a living.” Apparently, the left brain developed an on-the-fly interpretation of the laughter by finding something funny in the situation and claiming that this was the cause of his behavior. In another example, the instruction “walk” presented to the right brain resulted in the patient’s getting up to leave the testing van. On being asked where he was going, the patient’s left brain quickly improvised, “I’m going into the house to get a Coke” (Gazzaniga 1983).

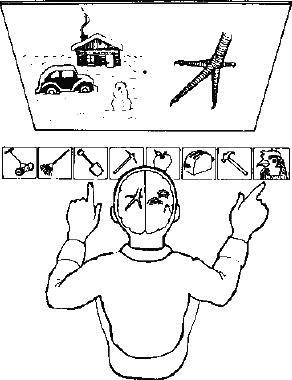

Similar observations were made of P. S., another patient with a modest but suitable level of verbal ability in the right brain. The patient was shown two pictures, one exclusively to the left brain and one exclusively to the right, and was asked to choose from another array of pictures in full view any ones that were associated with the pictures that had been flashed to each side of the brain. In the test shown in

figure 5.4

, a picture of a chicken claw was flashed to the right visual field, and so to the left brain. A picture of a snow scene was flashed to the left visual field and so to the right brain. Of the array of pictures in view, the best choices are the chicken for the chicken claw and the shovel for the snow scene. P. S. responded by choosing the shovel with the left hand (right brain) and the chicken with the right hand (left brain).

Figure 5.4

The upper images were flashed on the screen and so were channeled to the contralateral brain hemispheres. The patient P. S. was then asked to choose from the array of pictures below, the ones associated with those that were flashed. From Gazzaniga and LeDoux (1978). Courtesy Plenum Publishing.

When he was asked why he chose these things, P. S. was in something of a dilemma. The chicken choice was obvious enough to the left brain, as it had in fact engineered that choice. The chicken clearly went with the claw. But the shovel? Here was a choice made by the right brain, and the left brain had not played any part in making it. The left brain interpreter was up to the task, however, as P. S. responded, “Oh, that’s simple. The chicken claw goes with the chicken, and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed.” The left brain interpreted the right brain’s response according to a conindent consistent with its own sphere of knowledge and did so without being informed by the right brain’s knowledge of the snow scene.

To account for this and similar neuropsychological findings, Gazzaniga (1988) has suggested a brain-based theory of plasticity of intention:

Human brain architecture is organized in terms of functional modules capable of working both cooperatively and independently. These modules can carry out their functions in parallel and outside of the realm of conscious experience. The modules can effect internal and external behaviors, and do this at regular intervals. Monitoring all of this is a left-brain-based system called the interpreter. The interpreter considers all the outputs of the functional modules as soon as they are made and immediately constructs a hypothesis as to why particular actions occurred. In fact the interpreter need not be privy to why a particular module responded. Nonetheless, it will take the behavior at face value and fit the event into the large ongoing mental schema (belief system) that it has already constructed. (219)

This theory locates the invention of intention on the left side of the brain. It goes on to propose that the function of constructing postaction intentions is conducted on a regular basis by that side of the brain. It is interesting to wonder whether, when people do get their intentions clear in advance of acting, it is the same set of structures in the left brain that are involved. The split brain studies do not address the brain structures involved in producing the predictive awareness of action people enjoy when they do experience such awareness. The interpreter isolated by Gazzaniga does appear, however, to be a fine candidate for carrying out this function. The implication of the left brain interpreter theory is that whenever the interpreting happens, the interpretations are just narrations of the actions taken by other modules of the brain—both right and left—and are not causal of the actions at all.

The Three-Piece Puzzle

Will, intention, and action snap together like puzzle pieces. Consciousness of will derives from consciousness of intending and consciousness of acting, but this is not the only order in which the puzzle can be put together. Indeed, evidence of any two of these yields a presumption of the other.

In this chapter, we have seen a number of examples of action and the sense of conscious will leading to a postaction confabulation of intention. This is perhaps the best-researched relation among these variables, probably because it is so odd when people do it. We can’t help but notice and sometimes chuckle when people insist, “I meant to do that and wanted to all along” when we know full well they just happened into the action. Politicians, for example, seem to be under some of the most intense public pressure to maintain the image of being conscious agents, and their machinations in service of looking as though they had wanted something all along that later came out well are famous indeed. Vice President Al Gore’s 1999 claim in a CNN interview, “I took the initiative in creating the Internet,” for example, is exactly the sort of thing we all might like to do if we could get away with it. Gore’s comment went too far, of course, but such confabulated intentions often have the potential to make us look good—like conscious human agents, people who have willed what we do.

The equation can be worked in other directions as well. The perception that we have had a thought that is prior to, consistent with, and exclusively likely to be the cause of an action gives rise to experiences of conscious will. And perhaps when we experience a sense of conscious will or choice, and also have in mind a clear conscious intention, we may begin to fill in the third segment of the equation in another direction—by imagining, overperceiving, or confabulating a memory of the action itself. Consider what happens, for instance, when you are highly involved in playing or watching a game. It seems to be excruciatingly easy to misperceive the action of the game in accord with what you want to have happen. The tennis ball looks to be outside the line when you want it to be out, and inside when you want it to be in. The basketball player looks to be fouled in the act of shooting when you want the player’s team to win but not when you want the team to lose. A classic social psychological study called “They Saw a Game” by Hastorf and Cantril (1954) re-counted the wholesale misperception of the number of infractions on each side of a football game between Princeton and Dartmouth. Fans saw more infractions on the other side and blamed the other team for a dirty game. When we really want to do something, or even want to have our team do something, it seems easy to perceive that it was done. The ideal of conscious agency leads us not only to fabricate an experience of conscious will and to confabulate intentions consistent with that will, it also can blind us to our very actions, making us see them as far more effective than they actually are. After all, the actions must fit with the intention and the will.